Padre

Lord

General Report, End of Autumn IC 2401, Part 2

Is it Done?

Late Autumn in the City of Trantio, Central Tilea

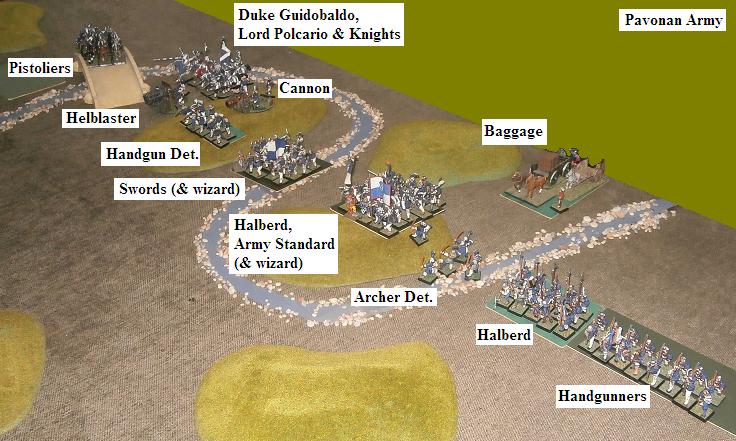

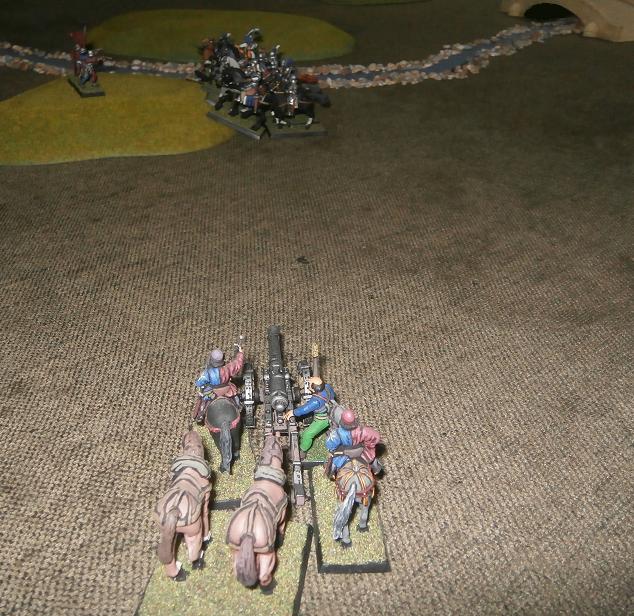

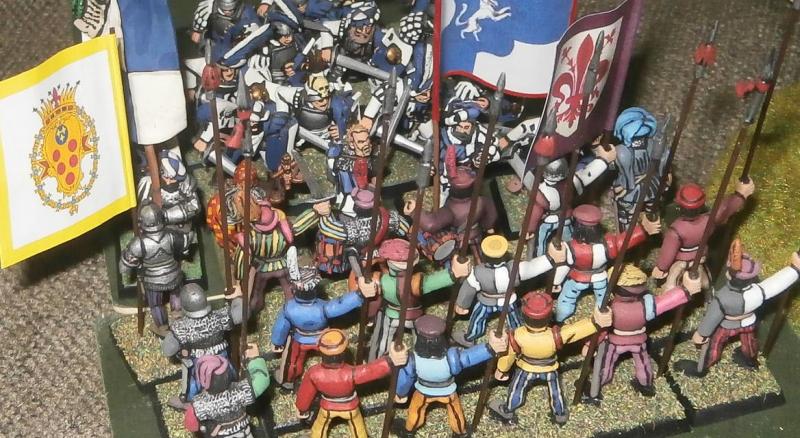

It was perhaps true that any other Tilean ruler would by now have been raging about the state of affairs, shouting his frustration at his council, complaining at the dishonesty, laziness or cowardice of mercenaries. Not Prince Girenzo of Trantio, however. His demeanour rarely seemed to change, and only the fact that he enquired four times a day for news had revealed how the matter weighed upon his mind. The condotta mercenaries of the Compagnia del Sole had had all the time they needed to strike at Pavona, time enough to have returned laden with loot. Yet they were still out there, skirting around the realm of Pavona like a scavenging fox looking for a cunning opportunity to strike without risk to itself. Every report they sent to the prince gave a different excuse. First there was the threat of the Pavonan army, reckoned to be far greater in strength than the Compagnia. Then there was trouble with moving the artillery. Then it was camp fever and the flux. Eventually, news came that they were at last to strike at the newly developed settlement in Venafro just east of the conquered city of Astiano. Since then, nothing. That is until now.

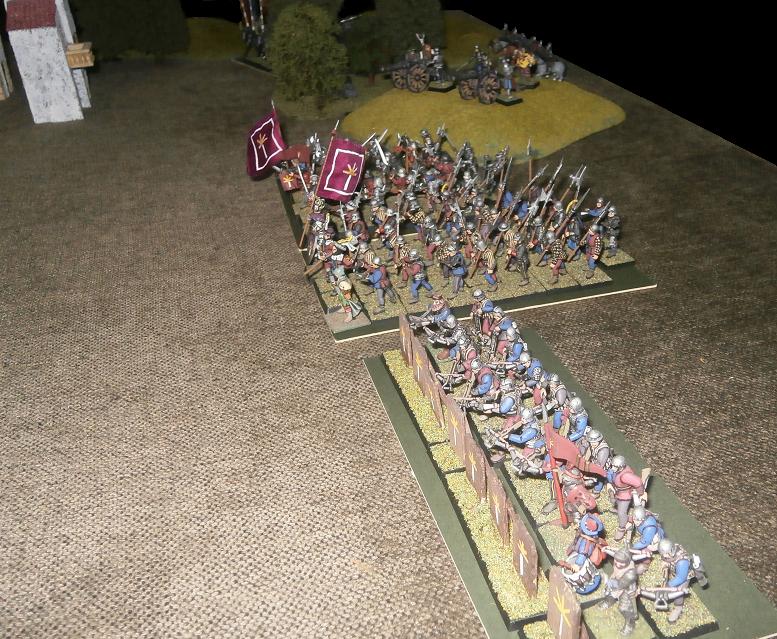

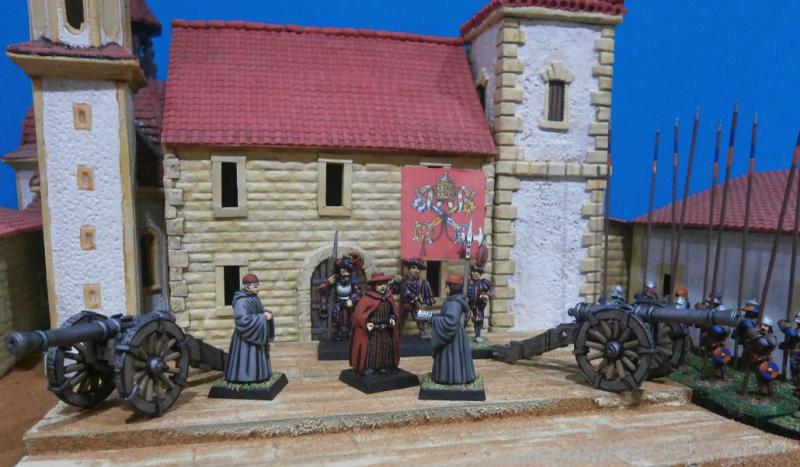

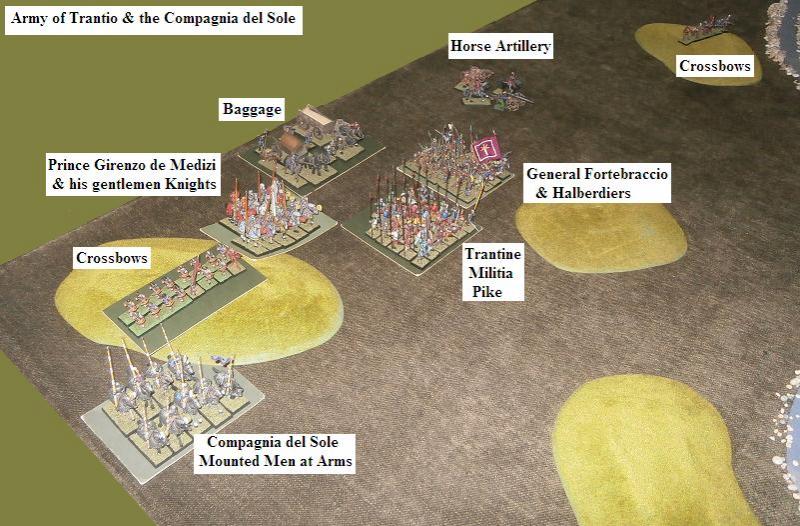

The prince was mounted and armoured, being engaged in military exercises with his gentlemen in the open field to the east of the city. It was a bright, blue sky day and he and his knights, bedecked as they were in plumes and their elaborately fluted armour, atop brightly barded horses, looked as if they had stepped out of the pages of a book of heroic tales. A little body of noblemen and officers, the prince’s ever-present councillors, stood chatting to one side, for the most part clad in the traditional burgundy and green of Trantio.

Upon sight of an approaching party, the prince had halted, ordering his men-at-arms to form a rank. He removed his exuberantly plumed helmet and watched as one man stepped forwards from the rest of the newly arrived company. It was a Compagnia del Sole captain called Duilio Citti who had brought the first set of excuses to be presented to the Duke over six weeks ago. The captain bowed, apparently a dab hand at that particular courtly etiquette, and then awaited the prince’s command.

“Do not tarry. Say what you’ve come to say,” the prince ordered in his quiet, clipped voice. Whether a felon was being dragged before him for judgement or a newly acquired horse was being led in for his inspection, the voice was always the same.

“Your grace, I bring better news this time. The Compagnia is victorious. Venafro is laid waste and a good deal of loot taken. The Pavonan army was outmanoeuvred and failed to catch us.”

The prince did not respond immediately, as it was not his way to rush. Like the others there, Captain Citti was forced to wait. The subsequent silence was interrupted only by the snorting of a horse and the pawing of another’s hooves at the dirt.

The captain wore a travelling cloak of soft leather over his blue and red tunic and hose. His own cap sported yellow and white feathers - the colours of the Compagnia’s Myrmidian emblem. The little company behind him, also garbed in blue and red accentuated with white and yellow, looked grimy and tired. Some had removed their helmets like peasants might remove their caps in front of their betters, but in the mercenaries’ case, they did so only for comfort. Indeed, it would normally be considered inappropriate for soldiers to doff their headgear in the presence of officers, or to adopt such a lazy posture. Veteran mercenaries, however, went by different rules.

“How far behind you are they?” asked the prince.

Captain Citti looked a little confused, as if he did not at first understand the question. “Your Grace, the Compagnia is not yet returning. They have laid siege to Astiano, that they might further harm Pavona.”

Prince Girenzo’s own captain, Sir Gino Saltaramenda, laughed. “So now, all of a sudden, the Compagnia has found courage?”

Captain Citti directed his answer to the prince, “We seek only to satisfy the terms of our contract, your grace, and to obey our orders.”

“You seek only to enrich yourselves,” said the prince, “which you can do best by not only being paid but taking a share of an even bigger haul of loot. I take it, then, that the Pavonan army are far removed, otherwise I doubt you would tarry so.”

“I know not exactly where the enemy is, but General Fortebraccio seemed satisfied that the risk was well worth taking. He does not intend to stay long at Astiano.”

“How so?” demanded the prince. “It is a walled town, is it not? Sieges take time.”

“It is walled, your grace, but there is little garrison to speak of, and they were previously conquered quickly and easily by the Pavonans.”

Again, Sir Gino laughed. “The Pavonans were no doubt willing to take casualties, which is why they carried the day in a storm. I very much doubt your own soldiers would wish to climb ladders as their comrades fall on all sides to lie heaped and dying in the ditches below.”

The mercenary captain flashed a defiant look at Sir Gino, giving a glimpse, perhaps, of just what he was capable of. A man such as he, a veteran condottiere soldier, had most likely been through hell several times over, and himself created hell for others as often. “The Compagnia’s fighting reputation is unblemished these past ten years. Myrmidia’s blessing is ever upon us. We fight when it proves necessary.”

“And will it?” asked the prince. “Will it ‘prove necessary’?”

“No, your grace. General Fortebraccio and his army council believe we can quickly extract a heavy fine from the Astianans. Once that is obtained, we can leave.”

“Let’s hope the people of Astiano do not realise you don’t actually intend to attack,” said Sir Gino.

“And let us hope that the Pavonan army does not arrive in time to catch you,” added the prince. “For then I would lose the fine, the Compagnia and the plunder already taken.”

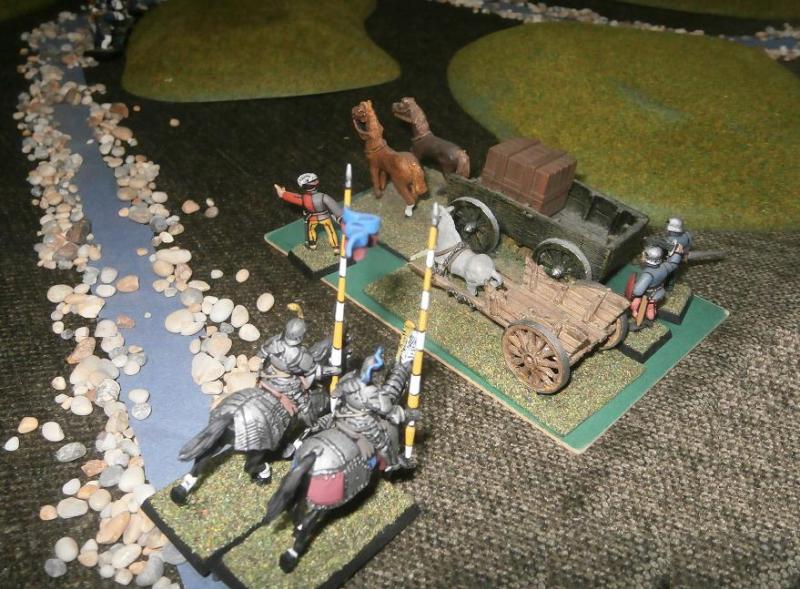

Captain Citti smiled, then gestured lazily to one of the men in the company behind him. “Sergino, the list.” A young man, unarmoured but sporting the Compagnia’s livery and girded with a heavy blade, strode forwards with a rolled paper in his hand. The captain continued, “This is a complete list of the plunder taken from Venafro, your grace.”

Prince Girenzo fixed his eyes upon Captain Citti. “We shall see when my agents inventory your baggage train, just how complete it is, shall we not?”

Sergino walked towards the prince himself, eliciting smirks from the mercenaries and annoyed looks from the Trantian councillors. He proffered the paper but Prince Girenzo ignored him. A man such as he did not simply stuff a note into the hand of a prince like Girenzo.

One of the councillors stepped forwards and coughed to catch Sergino’s attention, then beckoned him over with his finger.

Is it Done?

Late Autumn in the City of Trantio, Central Tilea

It was perhaps true that any other Tilean ruler would by now have been raging about the state of affairs, shouting his frustration at his council, complaining at the dishonesty, laziness or cowardice of mercenaries. Not Prince Girenzo of Trantio, however. His demeanour rarely seemed to change, and only the fact that he enquired four times a day for news had revealed how the matter weighed upon his mind. The condotta mercenaries of the Compagnia del Sole had had all the time they needed to strike at Pavona, time enough to have returned laden with loot. Yet they were still out there, skirting around the realm of Pavona like a scavenging fox looking for a cunning opportunity to strike without risk to itself. Every report they sent to the prince gave a different excuse. First there was the threat of the Pavonan army, reckoned to be far greater in strength than the Compagnia. Then there was trouble with moving the artillery. Then it was camp fever and the flux. Eventually, news came that they were at last to strike at the newly developed settlement in Venafro just east of the conquered city of Astiano. Since then, nothing. That is until now.

The prince was mounted and armoured, being engaged in military exercises with his gentlemen in the open field to the east of the city. It was a bright, blue sky day and he and his knights, bedecked as they were in plumes and their elaborately fluted armour, atop brightly barded horses, looked as if they had stepped out of the pages of a book of heroic tales. A little body of noblemen and officers, the prince’s ever-present councillors, stood chatting to one side, for the most part clad in the traditional burgundy and green of Trantio.

Upon sight of an approaching party, the prince had halted, ordering his men-at-arms to form a rank. He removed his exuberantly plumed helmet and watched as one man stepped forwards from the rest of the newly arrived company. It was a Compagnia del Sole captain called Duilio Citti who had brought the first set of excuses to be presented to the Duke over six weeks ago. The captain bowed, apparently a dab hand at that particular courtly etiquette, and then awaited the prince’s command.

“Do not tarry. Say what you’ve come to say,” the prince ordered in his quiet, clipped voice. Whether a felon was being dragged before him for judgement or a newly acquired horse was being led in for his inspection, the voice was always the same.

“Your grace, I bring better news this time. The Compagnia is victorious. Venafro is laid waste and a good deal of loot taken. The Pavonan army was outmanoeuvred and failed to catch us.”

The prince did not respond immediately, as it was not his way to rush. Like the others there, Captain Citti was forced to wait. The subsequent silence was interrupted only by the snorting of a horse and the pawing of another’s hooves at the dirt.

The captain wore a travelling cloak of soft leather over his blue and red tunic and hose. His own cap sported yellow and white feathers - the colours of the Compagnia’s Myrmidian emblem. The little company behind him, also garbed in blue and red accentuated with white and yellow, looked grimy and tired. Some had removed their helmets like peasants might remove their caps in front of their betters, but in the mercenaries’ case, they did so only for comfort. Indeed, it would normally be considered inappropriate for soldiers to doff their headgear in the presence of officers, or to adopt such a lazy posture. Veteran mercenaries, however, went by different rules.

“How far behind you are they?” asked the prince.

Captain Citti looked a little confused, as if he did not at first understand the question. “Your Grace, the Compagnia is not yet returning. They have laid siege to Astiano, that they might further harm Pavona.”

Prince Girenzo’s own captain, Sir Gino Saltaramenda, laughed. “So now, all of a sudden, the Compagnia has found courage?”

Captain Citti directed his answer to the prince, “We seek only to satisfy the terms of our contract, your grace, and to obey our orders.”

“You seek only to enrich yourselves,” said the prince, “which you can do best by not only being paid but taking a share of an even bigger haul of loot. I take it, then, that the Pavonan army are far removed, otherwise I doubt you would tarry so.”

“I know not exactly where the enemy is, but General Fortebraccio seemed satisfied that the risk was well worth taking. He does not intend to stay long at Astiano.”

“How so?” demanded the prince. “It is a walled town, is it not? Sieges take time.”

“It is walled, your grace, but there is little garrison to speak of, and they were previously conquered quickly and easily by the Pavonans.”

Again, Sir Gino laughed. “The Pavonans were no doubt willing to take casualties, which is why they carried the day in a storm. I very much doubt your own soldiers would wish to climb ladders as their comrades fall on all sides to lie heaped and dying in the ditches below.”

The mercenary captain flashed a defiant look at Sir Gino, giving a glimpse, perhaps, of just what he was capable of. A man such as he, a veteran condottiere soldier, had most likely been through hell several times over, and himself created hell for others as often. “The Compagnia’s fighting reputation is unblemished these past ten years. Myrmidia’s blessing is ever upon us. We fight when it proves necessary.”

“And will it?” asked the prince. “Will it ‘prove necessary’?”

“No, your grace. General Fortebraccio and his army council believe we can quickly extract a heavy fine from the Astianans. Once that is obtained, we can leave.”

“Let’s hope the people of Astiano do not realise you don’t actually intend to attack,” said Sir Gino.

“And let us hope that the Pavonan army does not arrive in time to catch you,” added the prince. “For then I would lose the fine, the Compagnia and the plunder already taken.”

Captain Citti smiled, then gestured lazily to one of the men in the company behind him. “Sergino, the list.” A young man, unarmoured but sporting the Compagnia’s livery and girded with a heavy blade, strode forwards with a rolled paper in his hand. The captain continued, “This is a complete list of the plunder taken from Venafro, your grace.”

Prince Girenzo fixed his eyes upon Captain Citti. “We shall see when my agents inventory your baggage train, just how complete it is, shall we not?”

Sergino walked towards the prince himself, eliciting smirks from the mercenaries and annoyed looks from the Trantian councillors. He proffered the paper but Prince Girenzo ignored him. A man such as he did not simply stuff a note into the hand of a prince like Girenzo.

One of the councillors stepped forwards and coughed to catch Sergino’s attention, then beckoned him over with his finger.