Padre

Lord

End of Season 5 (Spring 2402) General Report, Part 3 of 3

A Letter to Lord Lucca Vescucci of Verezzo

This to my most noble lord, from your loyal and obedient servant Antonio Mugello, being an account of my continuing travels in your service to gather true intelligence from the lands surrounding the beautiful realm of Verezzo.

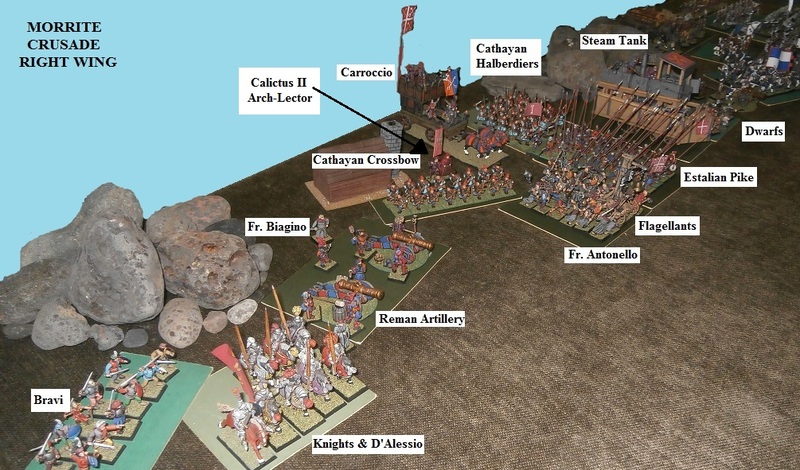

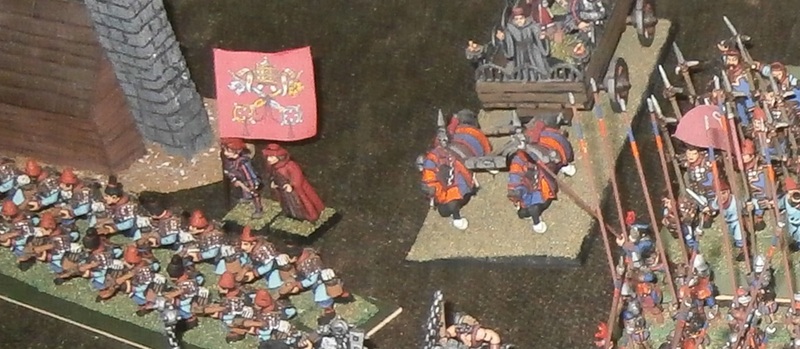

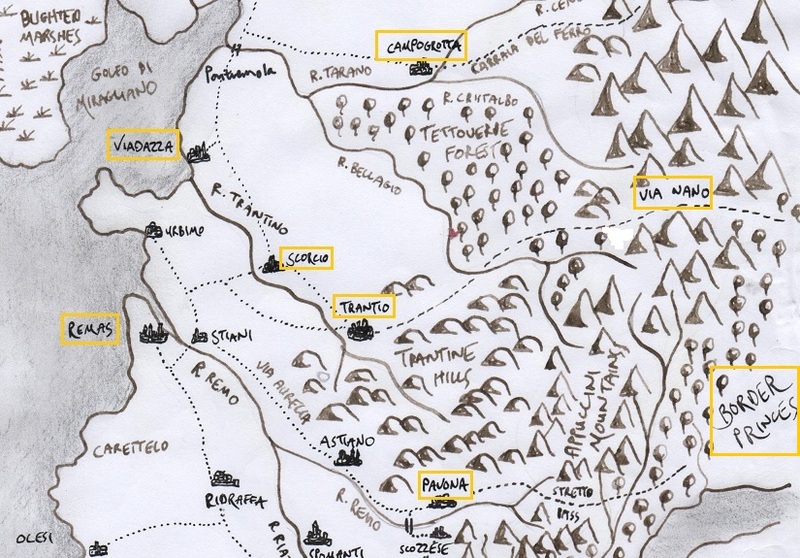

Having tarried sufficiently long in Remas to dispatch my earlier report, I determined to make my way to the newly conquered realm of Trantio, there to discover how that realm fares under the dominion of the conquering Duke Guidobaldo Gondi of Pavona, as well as to do what I could to ascertain the Duke’s intentions. Upon the day of my departure from Remas I witnessed the arrival of a regiment of brute ogres, accompanied by brigand archers, all hailing from the northern realm of Ravola. They processed through the streets led by several chanting priests of Morr, and all those who witnessed their passage declared them to be the strangest of crusaders - a quite unexpected addition to Morr’s holy army, yet not at all unwelcome.

I know full well that the people of Verezzo grow daily more concerned at the Pavonan duke’s conquests, for if both Astiano and now the entire city state of Trantio have fallen to him, then it is not inconceivable that the duke might turn his inquisitive - nay acquisitive - eyes upon Verezzo, especially in light of the Gondi family’s continued yet entirely unworthy and unwarranted complaints concerning the annulment of Lady Leonara’s marriage. Like so many recently ennobled families the Gondi’s pride has the sharp, hot edge born by those who still worry about their worthiness for such rank. Thus it is that Duke Guidobaldo is said to be as angry as ever at the unfortunate misunderstanding over his niece, although it is also whispered that he stirs the coals only to ensure he has a complaint ready to hand as an excuse for future military action.

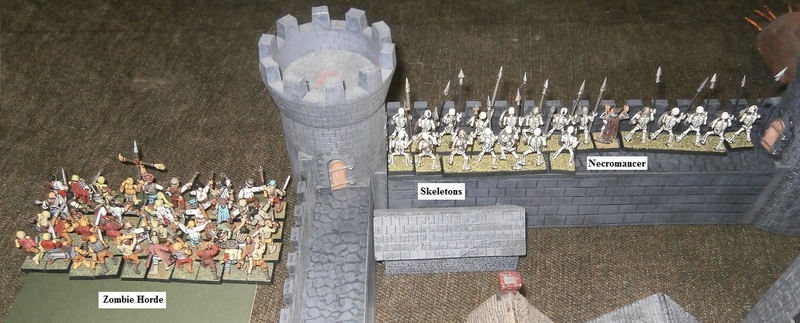

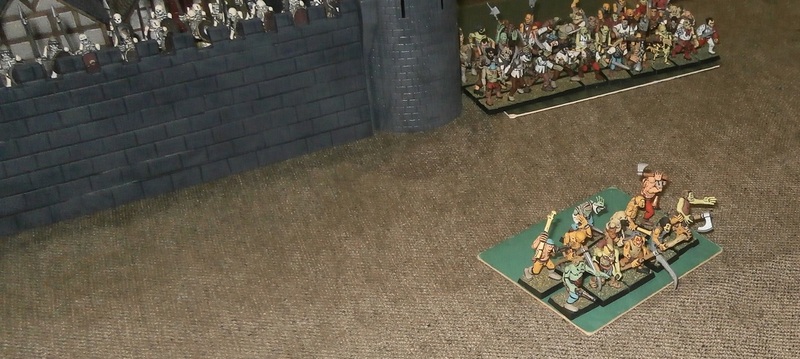

Upon arriving at Trantio, in the guise of a Reman petty-merchant, I immediately learned how oppressive is the new Pavonan rule, being not one jot less than that of the tyrant prince Girenzo, indeed, probably more so. The city was in a state of alert, having just learned that a sizeable army of mercenary ogres was upon the Via Nano with unknown intentions yet sensibly presumed to be unfriendly. This added to the native populace’s sense of unease over Duke Guidobaldo’s declaration that his surviving son, Lord Silvano, was now Gonfaloniere of Trantio, to become its de facto ruler when the duke himself left. Nor was the barely hidden bitterness ameliorated by the news that the region of Preto had been subdued, what resistance there was eliciting cruel reprisals by the Pavonan soldiery. This meant that the whole realm was now as one again, the city of Trantio - the town of Scorcio and the olive groves and vinyards of Preto - but it is a unity bought at a high price: the tyrannical oppression of Duke Guidobaldo. Ancient, proud Trantio has become a mere servant to Pavona.

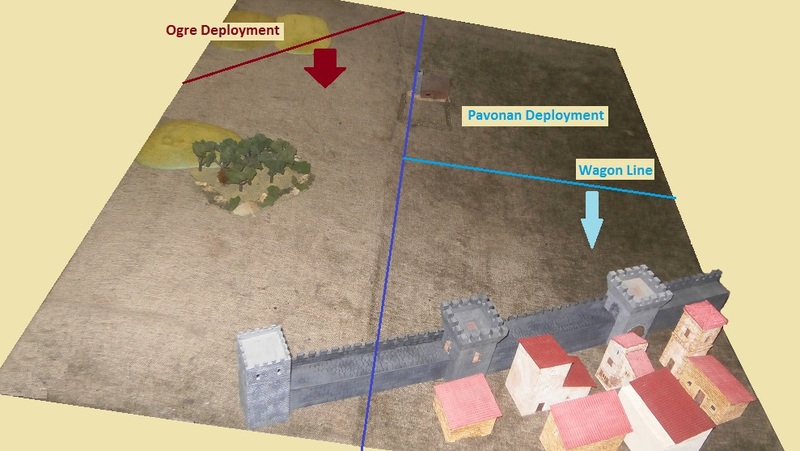

I lingered a few weeks to better judge the people’s mood and to learn what I could of the strength of the Pavonan forces present there. Here I humbly direct your attention, my lord, to the document accompanying this letter in which I attempt an accounting of said forces. Before I left Trantio to continue my journey I learned that a large fortified camp was being constructed near unto Scorcio. This seemed somewhat to alter the mood in the city, the common people now believing it possible that Duke Guidobaldo’s promises of Pavonan protection against the incursion of the dead may indeed be true, and that rather than simply burden them with taxes and impressment, the duke is indeed preparing to defend their realm. Nor is he intending to do so at the walls of Trantio itself, by which time the rest of the realm would surely have been lain waste, sacrificed to weaken and disperse the foe, but rather to make his stand at the northernmost borders, thereby halting the foe before they encroach upon the rest of the realm. Yet my Lord, you must not think this to mean I am certain of these matters, for I was unable to ascertain what exactly the Pavonan army intends to do next. Apart from a company of light horse sent to scout the Via Nano to learn of the mercenary ogres, I know not whether the rest of the army intends to remain at Trantio, occupy the fortified camp at Scorcio or march away to some other purpose. Duke Guidobaldo keeps his own counsel concerning such matters.

Thence I travelled towards Pavona itself, intending to reach that city in a week’s time. I write this from Astiano, which has become settled in its subservience to Pavona, and indeed has raised both a fighting regiment for their new master’s army and a militia to guard the town in Duke Guidobaldo’s service. I will send a letter to you as soon as I arrive in Pavona, where I hope to gain a much better understanding of the Pavonan’s intentions towards your fair city of Verezzo.

Ever and always your servant.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Camponeffro, South of Raverno

“There’s nothing here for us. Nothing of any worth, anyway” complained Pasquale for the third time that hour, his voice loud enough so those riding ahead of him could hear.

Tino answered, not bothering to turn in his saddle to look. “You knew that, Pas, before we even set off. We’re not here to loot, nor to have a holiday.”

“Never mind holidays and looting, there’s not even food or shelter. Fields all barren, cattle stolen, and what few folk we’ve found in a bad way and a worse mood. We may as well be in a desert.”

They had ridden for three days now, different companies of Portomaggioren soldiers scouring different parts of the region – this road, that village, this path – while some patrolled the forest edge at the southern border. The VMC had done a thorough job of sacking the place – it seemed northerners were no less adept at plundering than even the most veteran of Tilean mercenaries. Now all that remained were the ragged victims and scattered bands of brigands bolstered in numbers by the desperate and the dispossessed.

Tino gently slowed his mount’s pace until he was riding beside his irritable comrade. “You’re looking at it wrong. You should be glad that the northerners came, for if they had not fought Kurnag’s Waagh then I reckon it would have been us who had to do it.”

“I’ll tell you what I am looking at - this place!” countered Pasquale. “I’m looking at what the northerners did! They may be heroes for fighting the Waagh, but then they did this, turning honest farmers into beggars and robbers.”

“Aye, they did. But I say again, you’re still not seeing it right. Why not be glad the northerners attacked here instead of Portomaggiore?”

“Oh, I’m ecstatic about it. I suppose next you’ll be telling me that I ought to be happy I don’t have to carry all the loot they took, and that the wine they stole would’ve given me a headache in the morning, and that …”

“Hush now,” interrupted Tino, pointing ahead. “No shelter you said? That looks like shelter to me.”

It was a dwelling of modest size, which on first sight appeared as ruinous as nearly every other they had seen, but upon closer inspection had obviously been repaired, if in a haphazard and makeshift sort of way. The original roof was gone, replaced by a tangle of broken timbers supporting a canvass sheet. Faces peered over the walls.

Tino rode off the road through a gap in the hedge. Three of the column, including Pasquale, followed him. The other riders did not share Tino’s curiosity and carried on down the road, tired of this miserable land and its meagre pickings. Besides the place was too small for all of them, and they knew they would have to find somewhere else for the night.

As Tino drew close he saw three inhabitants who were everything he had come to expect from this region – an old, bent man leaning heavy on a stick, a battered and bruised peasant with his arm in a sling, and a wench carrying nothing more exciting than a bundle of twigs.

“You there,” shouted Tino, having unholstered his long horseman’s pistol, a habit formed from bitter experience over the last few days. “Is this place yours?”

“What’s left of it, aye,” said the injured man in a thick Ravernan accent. “All ours. Why? Are you intending to smash it up some more?”

Pasquale laughed. “There’s not much left to break, friend.”

“You needn’t fear us,” reassured Tino. “We’re here to make things better, not worse. Stupid question, I know, but who did this?”

“Foreigners, of the ultramontane kind,” said the old man in a croaky voice.

Tino asked the question he had been using a lot recently. “Why?”

Now the old man gave vent to a bitter laugh. “Because this is what soldiers do. I know, I was one once.”

“No, old man. I meant why here and not somewhere else? Why attack Camponeffro?”

“They said we were being punished,” said the man with an arm in a sling. “I told them I hadn’t done anything to them and this is what I got.” He held up his injured arm.

Tino frowned. This was new. “Punished for what?”

“I don’t know,” said the wounded man. “Having hens? Being nearby?”

The old man coughed and everyone looked at him. “They said, ‘This will teach you not to throw Marienburgers out of windows.’”

Pasquale swept his hand as if to indicate all around. “Seems a bit too much punishment for a spot of tomfoolery and rough and tumble,” he said.

“That was their excuse,” said the old man. “Not their real purpose. When I was a soldier we found fighting greenskins to be a very unprofitable affair. The sort of things they treasured weren’t exactly what we wanted to loot. I reckon the ultramontanes came here because they needed pay, and plucked at any old excuse to make what they were doing seem more than mere robbery.”

“You can tell us about your adventures over supper, old man,” said Tino, smiling. “In the meantime, wench, how about using your burden to get a fire burning? Oh, and what have you got to eat?”

A Letter to Lord Lucca Vescucci of Verezzo

This to my most noble lord, from your loyal and obedient servant Antonio Mugello, being an account of my continuing travels in your service to gather true intelligence from the lands surrounding the beautiful realm of Verezzo.

Having tarried sufficiently long in Remas to dispatch my earlier report, I determined to make my way to the newly conquered realm of Trantio, there to discover how that realm fares under the dominion of the conquering Duke Guidobaldo Gondi of Pavona, as well as to do what I could to ascertain the Duke’s intentions. Upon the day of my departure from Remas I witnessed the arrival of a regiment of brute ogres, accompanied by brigand archers, all hailing from the northern realm of Ravola. They processed through the streets led by several chanting priests of Morr, and all those who witnessed their passage declared them to be the strangest of crusaders - a quite unexpected addition to Morr’s holy army, yet not at all unwelcome.

I know full well that the people of Verezzo grow daily more concerned at the Pavonan duke’s conquests, for if both Astiano and now the entire city state of Trantio have fallen to him, then it is not inconceivable that the duke might turn his inquisitive - nay acquisitive - eyes upon Verezzo, especially in light of the Gondi family’s continued yet entirely unworthy and unwarranted complaints concerning the annulment of Lady Leonara’s marriage. Like so many recently ennobled families the Gondi’s pride has the sharp, hot edge born by those who still worry about their worthiness for such rank. Thus it is that Duke Guidobaldo is said to be as angry as ever at the unfortunate misunderstanding over his niece, although it is also whispered that he stirs the coals only to ensure he has a complaint ready to hand as an excuse for future military action.

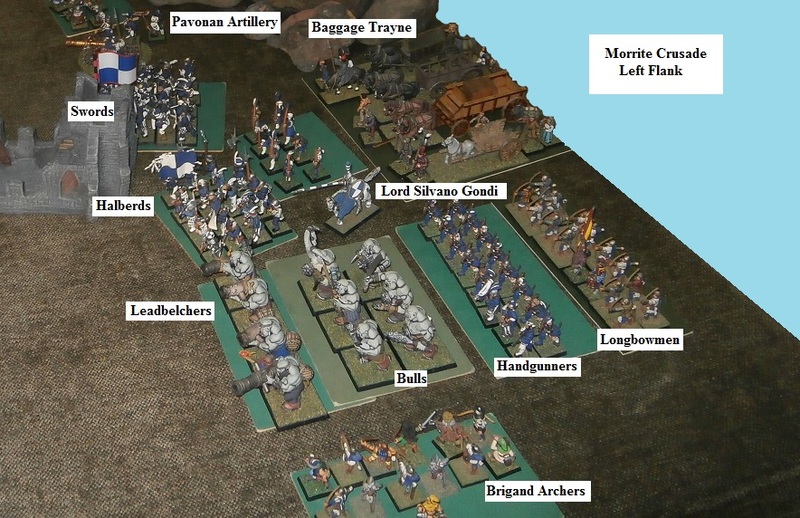

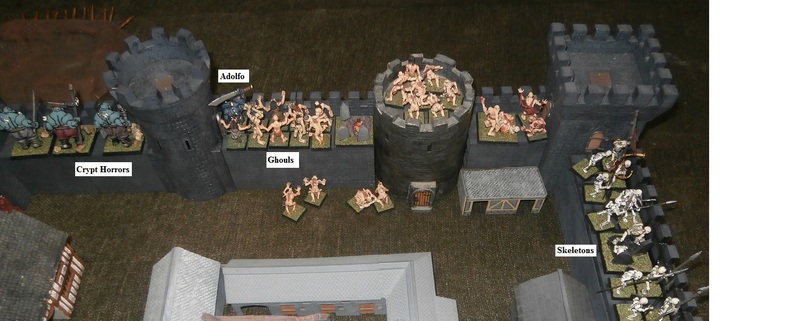

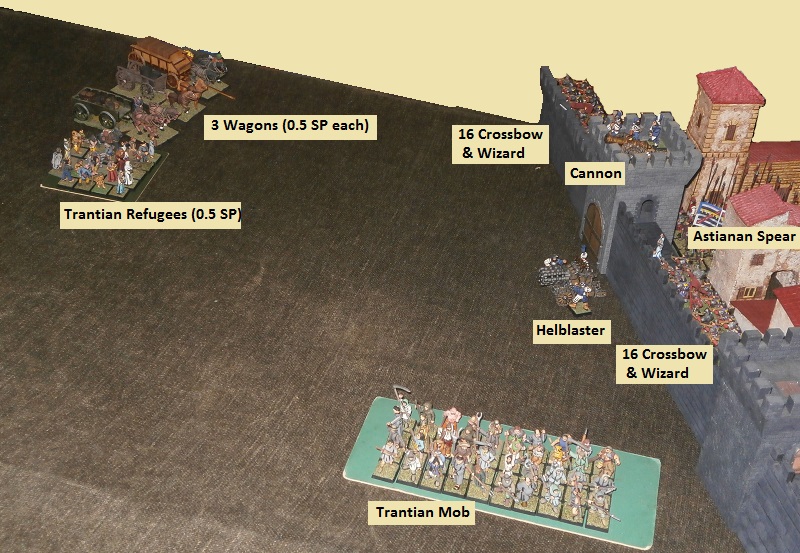

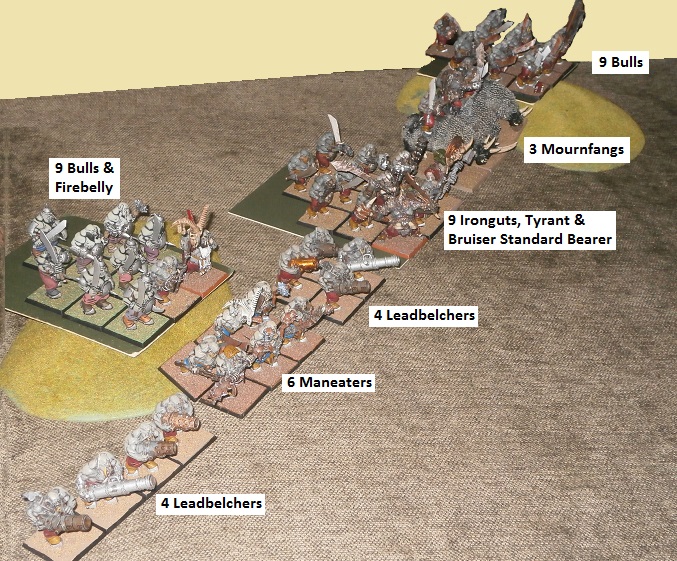

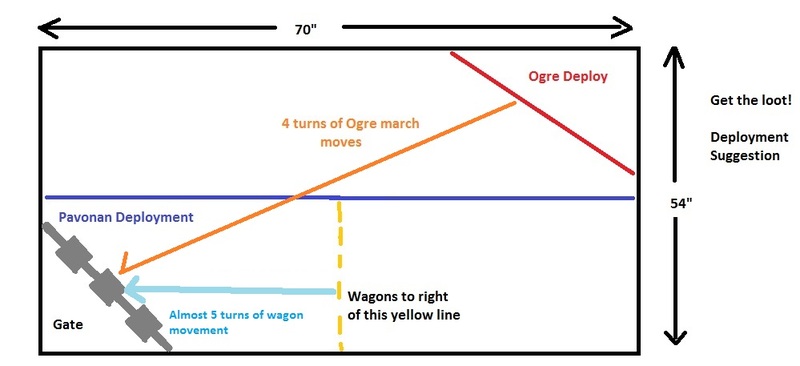

Upon arriving at Trantio, in the guise of a Reman petty-merchant, I immediately learned how oppressive is the new Pavonan rule, being not one jot less than that of the tyrant prince Girenzo, indeed, probably more so. The city was in a state of alert, having just learned that a sizeable army of mercenary ogres was upon the Via Nano with unknown intentions yet sensibly presumed to be unfriendly. This added to the native populace’s sense of unease over Duke Guidobaldo’s declaration that his surviving son, Lord Silvano, was now Gonfaloniere of Trantio, to become its de facto ruler when the duke himself left. Nor was the barely hidden bitterness ameliorated by the news that the region of Preto had been subdued, what resistance there was eliciting cruel reprisals by the Pavonan soldiery. This meant that the whole realm was now as one again, the city of Trantio - the town of Scorcio and the olive groves and vinyards of Preto - but it is a unity bought at a high price: the tyrannical oppression of Duke Guidobaldo. Ancient, proud Trantio has become a mere servant to Pavona.

I lingered a few weeks to better judge the people’s mood and to learn what I could of the strength of the Pavonan forces present there. Here I humbly direct your attention, my lord, to the document accompanying this letter in which I attempt an accounting of said forces. Before I left Trantio to continue my journey I learned that a large fortified camp was being constructed near unto Scorcio. This seemed somewhat to alter the mood in the city, the common people now believing it possible that Duke Guidobaldo’s promises of Pavonan protection against the incursion of the dead may indeed be true, and that rather than simply burden them with taxes and impressment, the duke is indeed preparing to defend their realm. Nor is he intending to do so at the walls of Trantio itself, by which time the rest of the realm would surely have been lain waste, sacrificed to weaken and disperse the foe, but rather to make his stand at the northernmost borders, thereby halting the foe before they encroach upon the rest of the realm. Yet my Lord, you must not think this to mean I am certain of these matters, for I was unable to ascertain what exactly the Pavonan army intends to do next. Apart from a company of light horse sent to scout the Via Nano to learn of the mercenary ogres, I know not whether the rest of the army intends to remain at Trantio, occupy the fortified camp at Scorcio or march away to some other purpose. Duke Guidobaldo keeps his own counsel concerning such matters.

Thence I travelled towards Pavona itself, intending to reach that city in a week’s time. I write this from Astiano, which has become settled in its subservience to Pavona, and indeed has raised both a fighting regiment for their new master’s army and a militia to guard the town in Duke Guidobaldo’s service. I will send a letter to you as soon as I arrive in Pavona, where I hope to gain a much better understanding of the Pavonan’s intentions towards your fair city of Verezzo.

Ever and always your servant.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Camponeffro, South of Raverno

“There’s nothing here for us. Nothing of any worth, anyway” complained Pasquale for the third time that hour, his voice loud enough so those riding ahead of him could hear.

Tino answered, not bothering to turn in his saddle to look. “You knew that, Pas, before we even set off. We’re not here to loot, nor to have a holiday.”

“Never mind holidays and looting, there’s not even food or shelter. Fields all barren, cattle stolen, and what few folk we’ve found in a bad way and a worse mood. We may as well be in a desert.”

They had ridden for three days now, different companies of Portomaggioren soldiers scouring different parts of the region – this road, that village, this path – while some patrolled the forest edge at the southern border. The VMC had done a thorough job of sacking the place – it seemed northerners were no less adept at plundering than even the most veteran of Tilean mercenaries. Now all that remained were the ragged victims and scattered bands of brigands bolstered in numbers by the desperate and the dispossessed.

Tino gently slowed his mount’s pace until he was riding beside his irritable comrade. “You’re looking at it wrong. You should be glad that the northerners came, for if they had not fought Kurnag’s Waagh then I reckon it would have been us who had to do it.”

“I’ll tell you what I am looking at - this place!” countered Pasquale. “I’m looking at what the northerners did! They may be heroes for fighting the Waagh, but then they did this, turning honest farmers into beggars and robbers.”

“Aye, they did. But I say again, you’re still not seeing it right. Why not be glad the northerners attacked here instead of Portomaggiore?”

“Oh, I’m ecstatic about it. I suppose next you’ll be telling me that I ought to be happy I don’t have to carry all the loot they took, and that the wine they stole would’ve given me a headache in the morning, and that …”

“Hush now,” interrupted Tino, pointing ahead. “No shelter you said? That looks like shelter to me.”

It was a dwelling of modest size, which on first sight appeared as ruinous as nearly every other they had seen, but upon closer inspection had obviously been repaired, if in a haphazard and makeshift sort of way. The original roof was gone, replaced by a tangle of broken timbers supporting a canvass sheet. Faces peered over the walls.

Tino rode off the road through a gap in the hedge. Three of the column, including Pasquale, followed him. The other riders did not share Tino’s curiosity and carried on down the road, tired of this miserable land and its meagre pickings. Besides the place was too small for all of them, and they knew they would have to find somewhere else for the night.

As Tino drew close he saw three inhabitants who were everything he had come to expect from this region – an old, bent man leaning heavy on a stick, a battered and bruised peasant with his arm in a sling, and a wench carrying nothing more exciting than a bundle of twigs.

“You there,” shouted Tino, having unholstered his long horseman’s pistol, a habit formed from bitter experience over the last few days. “Is this place yours?”

“What’s left of it, aye,” said the injured man in a thick Ravernan accent. “All ours. Why? Are you intending to smash it up some more?”

Pasquale laughed. “There’s not much left to break, friend.”

“You needn’t fear us,” reassured Tino. “We’re here to make things better, not worse. Stupid question, I know, but who did this?”

“Foreigners, of the ultramontane kind,” said the old man in a croaky voice.

Tino asked the question he had been using a lot recently. “Why?”

Now the old man gave vent to a bitter laugh. “Because this is what soldiers do. I know, I was one once.”

“No, old man. I meant why here and not somewhere else? Why attack Camponeffro?”

“They said we were being punished,” said the man with an arm in a sling. “I told them I hadn’t done anything to them and this is what I got.” He held up his injured arm.

Tino frowned. This was new. “Punished for what?”

“I don’t know,” said the wounded man. “Having hens? Being nearby?”

The old man coughed and everyone looked at him. “They said, ‘This will teach you not to throw Marienburgers out of windows.’”

Pasquale swept his hand as if to indicate all around. “Seems a bit too much punishment for a spot of tomfoolery and rough and tumble,” he said.

“That was their excuse,” said the old man. “Not their real purpose. When I was a soldier we found fighting greenskins to be a very unprofitable affair. The sort of things they treasured weren’t exactly what we wanted to loot. I reckon the ultramontanes came here because they needed pay, and plucked at any old excuse to make what they were doing seem more than mere robbery.”

“You can tell us about your adventures over supper, old man,” said Tino, smiling. “In the meantime, wench, how about using your burden to get a fire burning? Oh, and what have you got to eat?”