You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Tilea IC2401 (Campaign#8)

- Thread starter Padre

- Start date

symphonicpoet

Moderator

^I wouldn't feel too bad for the horse. There's no way he's blowing that horn with his visor down. Maybe it's a megaphone and he's shouting orders. That wouldn't be great, but it'd probably still be better than a cornet in the ear.

Anyway . . . lovely stuff, Padre. Absolutely lovely!

Anyway . . . lovely stuff, Padre. Absolutely lovely!

Caradepato

Vassal

Thats a great helm.... doesn't have a movable visor, so the guy is just pretending. Makes me think of the Monty Python scene where the spanish inquisitions ties a woman to a drying rack and pretend to torture her.

Padre

Lord

Part 8 of Tilea's Troubles is done and uploaded!

https://youtu.be/mz86e8glWFY

I think I forgot to put a link to part 7 here? It's at https://youtu.be/F7N_k1AHIMA

https://youtu.be/mz86e8glWFY

I think I forgot to put a link to part 7 here? It's at https://youtu.be/F7N_k1AHIMA

Padre

Lord

Part 9 of Tilea's Troubles is uploaded:

Link - https://youtu.be/h7L2ryx2kEM

(Yes, those heavily milliputted figures are ancient, and still in their 1980's paint job. A good friend of mine painted them when we were students.)

I am also currently in the middle of making scenery for one of the next battles, as well as writing a new story for the campaign thread, not just more video stories from early in the campaign. This will involved many new pictures and perhaps some painting. There are three battles to do soon, although I do not know whether to wait until the lockdown rules allow us to play them together or whether I should do one or two of them as play by e-mail like the last three! There are also so many new stories I want to do that I might slow down the pace of doing the videos of old stories for a few weeks!

Link - https://youtu.be/h7L2ryx2kEM

(Yes, those heavily milliputted figures are ancient, and still in their 1980's paint job. A good friend of mine painted them when we were students.)

I am also currently in the middle of making scenery for one of the next battles, as well as writing a new story for the campaign thread, not just more video stories from early in the campaign. This will involved many new pictures and perhaps some painting. There are three battles to do soon, although I do not know whether to wait until the lockdown rules allow us to play them together or whether I should do one or two of them as play by e-mail like the last three! There are also so many new stories I want to do that I might slow down the pace of doing the videos of old stories for a few weeks!

Padre

Lord

Now back to the campaign's 'present day' stories ...

Pavona’s Hero

Summer, 2401, The City of Pavona

The sound of drums could be heard, growing louder. Giovacchino leaned forwards to look over the crowd between him and the street. When the strong ale in his pot sloshed and threatened to spill, he relaxed a little turned to his companion.

“I think this is lunacy,” he announced. “There’s a new war brewing, right on our very doorstep. I think the bloody Verezzans believe they’re strong enough to take us on. Even if they’re not sure, they might be bitter enough to try anyway. Yet Lord Silvano is taking nearly the entire army away on another foreign war! We should finish off the Verezzans first - put an end to their pathetic whining and make sure they don’t try anything else.”

Corporal Aldus was also peering down the street, and answered without glancing at his friend, “Why don’t you take the matter up with the duke?”

“I’m taking the matter up with you!” said Giovacchino. “Look, see, I know this is what Lord Silvano does - riding off to fight monstrous foes - but there’s a time and a place for that sort of nonsense. This ain’t the time at all, and Campogrotta’s too far away to be the right place. I mean, do the Campogrottans even need our help? They’ve an entire bloody army of their own, and that the gods-forsaken Compagnia del Sole, cousins of the very enemy that put us to all that trouble years ago. Why in all the hells are we sending our boys to do the fighting for them? I tell you, there’s no part of this makes sense.”

A company of drummers, being the first in the column, were now passing by, beating up a jaunty march indeed, which was everything to do with this sort of parade and nothing to do with battle calls.

“So, let me get this straight,” said the corporal. “You’re questioning the duke’s orders, yes? Well, my answer to you, my friend, would be that you should think hard about what you say and who you say it to.”

“No, no, no! I’m no fool,” replied Giovacchino. “I’m not saying the Duke is wrong. I just want to understand it myself.”

“Look, the duke’s a hard man, noble, yes, but a man of war. He takes whatever he believes is his by right. He doesn’t suffer fools and exacts swift vengeance on all who trouble him in any way whatsoever. And yet, all that said, what father would deny his only beloved son?”

“Aye, well, that only shifts the blame to the son. Doesn’t make the decision any less foolish.”

Corporal Aldus fixed his stare on Giovacchino. “You’re really not listening, are you? I already warned you - have a care! There are many would take offence to such words. I shall assume you’re trying to understand why Lord Silvano wants to go.”

“That’s it. That’s all. Why?”

“That’s easy. Lord Silvano is what you call a hero, always has been. I reckon since his brother died fighting Prince Girenzo, he’s been desperate to prove himself a worthy successor in his father’s eyes, to show he’s afraid of no challenge and willing to take on any foe.”

“So, you’re saying our army marches off when we’re at our weakest, and when our closest neighbours and others besides have a whole bag o’ bones to pick with us, because a young lord wants to prove his mettle? Maybe he should worry more about being a worthy successor to rule Pavona when his father dies, and to do that he needs to be alive, and there needs to be a bloody Pavona left to rule.”

“You can’t help yourself, can you? Your mouth’ll be the end of you one day, if you don’t die on the end of an enemy’s blade. Stop complaining. We have the city militia, and I reckon there’s many an old soldier would happily muster for the city’s defence if it proved necessary. Pavona will survive and grow strong again. Who cares how loud the Verezzan dogs bay and howl? Any one of us could take on three of them.”

The drummers had passed by, although the sound they made was still filling the street. Now came the colours, marching together as a little company of ensigns. All were quartered blue and white, with some little extra added to each to mark them out on the field – a border, or tassels or a symbol upon the white.

Giovacchino sniffed. Then in a quieter voice said,

“It’s not just them though, is it? The VMC scum have unfinished business with us – they left off their siege only because they were persuaded the undead were the bigger problem. And the Verezzans may have been weak in the past, but everyone says they’re building an army squarely intent on revenge for Lord Lucca’s death. Their petty, brigand robbers have already begun the fight, sneaking about in the shadows to pick off our soldiers when they can get away with it without risking a fight. Scouting for them; learning the lay of the land.”

Corporal Aldus grinned. “Then it’s no bad thing Lord Silvano is marching our boys away, ‘cos then brigands won’t be able to kill them.”

Giovacchino spoke even quieter than before. “Except we’ll be among the few that remain, and it’ll be us they’re loosing their arrows at.”

Still cheerful, despite the notion, the corporal said, “I didn’t think of that.”

Now came a body of handgunners, one of which stared over at Aldus and Giovacchino as they passed.

“There’s Mariano,” said Aldus. “Does he still owe you sixteen silvers?”

“Aye. He’d better bloody survive ‘cos I need that money.”

“He’ll survive. He’s always been careful. Once told me he never fired his piece in that fight in the Trantine Hills. When I asked him why, he said it was so he wouldn’t have to clean it afterwards.”

“That’s the wrong sort of careful. The stupid sort!” laughed Giovacchino. “Aldus, you say be careful of my words, but it seems to me most people ain’t too pleased about the army leaving. The best anyone could say about this crowd is that it is respectful. None would claim any signs of enthusiasm.”

“They’re just tired,” said the corporal, whose head still ached from the old wound.

“Ha!” laughed Giovacchino. “They’re tired? They want to try marching all the way to Trantio and back, with only fighting to break the journey. If Lord Silvano has the urge to fight a righteous war, then why isn’t he going off to help in the march on Miragliano. The priests are always preaching that we live in Morr’s most cherished realm. Shouldn’t he be fighting the undead?”

“Oh, it’s too late for that,” said Aldus. “Duke Guidobaldo announced in his address that the war against the vampires is all but over. The enemy lost army after army trying to take on the Portomaggiorans and Remans, and now they’ve got the VMC against them too. All that’s left is the filthy job of cleaning up Miragliano, and I wouldn’t waste Pavonan lives on such nasty work. I reckon more’ll die of disease in such a wretched realm than in battle! If that war is over, then Lord Silvano obviously wants to make sure that the ratto uomo don’t gain an advantage while the living realms are weakened by the fight against the undead. Verminkind love ruinous places, and the north is one big ruin right now.”

“Not just the north,” said Giovacchino. “Pavona’s no better! All Boulderguts left us is the city and the southern side of the river. Astiano and Trantio are ruined too. Every realm hereabouts is as sickly and broken as the north.”

“Then praise the gods that our brave young lord is helping to quash the threat of ratmen before they grow too powerful.”

As the corporal spoke, he gestured to the street, for Lord Silvano himself, clad in brightly silvered armour and sporting a tall panache-crest of blue and white, his lance lowered as if to indicate his intention to advance, rode into view.

By the young lord’s side rode his knghtly standard bearer, and behind him rode the city’s young nobility, their shields decorated with Morr’s fleshless head, crowned as king of the gods.

“If you have the answer to everything, Aldus, then tell me this: Why didn’t the duke send Visconte Carjaval with the army instead of his only son and heir?”

“Oh, that was the plan. The Visconte had orders to that effect. But then the orders changed. You didn’t attend the temple this morning, did you?”

“My head still hurt from last night. Why? D’you think my soul’s in need of cleansing?”

“Ha! That and the rest of you!”

Giovacchino sniffed at his armpit, spilling some of the ale as he did so, then cursing.

“What about the temple?” he demanded. “Did you receive divine enlightenment? That’d explain all your answers.”

“The priest prayed for Lord Silvano’s success, then told us how the duke knew his son possessed a compassionate heart and a desire to serve the lawful gods, Morr Supreme above all, and that he yearned to defend the innocent, weak, the young and old, from all further upsets. Apparently, the duke even said his son was the better man than he, for where he had always taken rightful anger to bloody conclusion, his son was willing to temper his reactions with an urge to understand and forgive.”

Giovacchino frowned. “That doesn’t sound like the sort of thing the duke would say.”

“Maybe not, but that’s what the priest told us. And more than that, he said the duke had vowed to live ‘quiete and pacifice’ until his son’s safe return from victory.”

“Oh, that’s lovely,” said Giovacchino sarcastically. “It’s like poetry, ain’t it?” Then, more seriously, he asked. “Doesn’t sound like the duke either. Tell me though, is it true? Will the fighting end?”

Aldus shrugged. “I suppose if the Verezzan brigands stop what they’re doing, and everyone else leaves us alone for a while, then why not? Besides, the answer’s right in front of you. The army’s marching off. Say farewell to the young lord and our army.”

“Ha!” laughed Giovacchino. “And say hello to some peace and quiet.”

Pavona’s Hero

Summer, 2401, The City of Pavona

The sound of drums could be heard, growing louder. Giovacchino leaned forwards to look over the crowd between him and the street. When the strong ale in his pot sloshed and threatened to spill, he relaxed a little turned to his companion.

“I think this is lunacy,” he announced. “There’s a new war brewing, right on our very doorstep. I think the bloody Verezzans believe they’re strong enough to take us on. Even if they’re not sure, they might be bitter enough to try anyway. Yet Lord Silvano is taking nearly the entire army away on another foreign war! We should finish off the Verezzans first - put an end to their pathetic whining and make sure they don’t try anything else.”

Corporal Aldus was also peering down the street, and answered without glancing at his friend, “Why don’t you take the matter up with the duke?”

“I’m taking the matter up with you!” said Giovacchino. “Look, see, I know this is what Lord Silvano does - riding off to fight monstrous foes - but there’s a time and a place for that sort of nonsense. This ain’t the time at all, and Campogrotta’s too far away to be the right place. I mean, do the Campogrottans even need our help? They’ve an entire bloody army of their own, and that the gods-forsaken Compagnia del Sole, cousins of the very enemy that put us to all that trouble years ago. Why in all the hells are we sending our boys to do the fighting for them? I tell you, there’s no part of this makes sense.”

A company of drummers, being the first in the column, were now passing by, beating up a jaunty march indeed, which was everything to do with this sort of parade and nothing to do with battle calls.

“So, let me get this straight,” said the corporal. “You’re questioning the duke’s orders, yes? Well, my answer to you, my friend, would be that you should think hard about what you say and who you say it to.”

“No, no, no! I’m no fool,” replied Giovacchino. “I’m not saying the Duke is wrong. I just want to understand it myself.”

“Look, the duke’s a hard man, noble, yes, but a man of war. He takes whatever he believes is his by right. He doesn’t suffer fools and exacts swift vengeance on all who trouble him in any way whatsoever. And yet, all that said, what father would deny his only beloved son?”

“Aye, well, that only shifts the blame to the son. Doesn’t make the decision any less foolish.”

Corporal Aldus fixed his stare on Giovacchino. “You’re really not listening, are you? I already warned you - have a care! There are many would take offence to such words. I shall assume you’re trying to understand why Lord Silvano wants to go.”

“That’s it. That’s all. Why?”

“That’s easy. Lord Silvano is what you call a hero, always has been. I reckon since his brother died fighting Prince Girenzo, he’s been desperate to prove himself a worthy successor in his father’s eyes, to show he’s afraid of no challenge and willing to take on any foe.”

“So, you’re saying our army marches off when we’re at our weakest, and when our closest neighbours and others besides have a whole bag o’ bones to pick with us, because a young lord wants to prove his mettle? Maybe he should worry more about being a worthy successor to rule Pavona when his father dies, and to do that he needs to be alive, and there needs to be a bloody Pavona left to rule.”

“You can’t help yourself, can you? Your mouth’ll be the end of you one day, if you don’t die on the end of an enemy’s blade. Stop complaining. We have the city militia, and I reckon there’s many an old soldier would happily muster for the city’s defence if it proved necessary. Pavona will survive and grow strong again. Who cares how loud the Verezzan dogs bay and howl? Any one of us could take on three of them.”

The drummers had passed by, although the sound they made was still filling the street. Now came the colours, marching together as a little company of ensigns. All were quartered blue and white, with some little extra added to each to mark them out on the field – a border, or tassels or a symbol upon the white.

Giovacchino sniffed. Then in a quieter voice said,

“It’s not just them though, is it? The VMC scum have unfinished business with us – they left off their siege only because they were persuaded the undead were the bigger problem. And the Verezzans may have been weak in the past, but everyone says they’re building an army squarely intent on revenge for Lord Lucca’s death. Their petty, brigand robbers have already begun the fight, sneaking about in the shadows to pick off our soldiers when they can get away with it without risking a fight. Scouting for them; learning the lay of the land.”

Corporal Aldus grinned. “Then it’s no bad thing Lord Silvano is marching our boys away, ‘cos then brigands won’t be able to kill them.”

Giovacchino spoke even quieter than before. “Except we’ll be among the few that remain, and it’ll be us they’re loosing their arrows at.”

Still cheerful, despite the notion, the corporal said, “I didn’t think of that.”

Now came a body of handgunners, one of which stared over at Aldus and Giovacchino as they passed.

“There’s Mariano,” said Aldus. “Does he still owe you sixteen silvers?”

“Aye. He’d better bloody survive ‘cos I need that money.”

“He’ll survive. He’s always been careful. Once told me he never fired his piece in that fight in the Trantine Hills. When I asked him why, he said it was so he wouldn’t have to clean it afterwards.”

“That’s the wrong sort of careful. The stupid sort!” laughed Giovacchino. “Aldus, you say be careful of my words, but it seems to me most people ain’t too pleased about the army leaving. The best anyone could say about this crowd is that it is respectful. None would claim any signs of enthusiasm.”

“They’re just tired,” said the corporal, whose head still ached from the old wound.

“Ha!” laughed Giovacchino. “They’re tired? They want to try marching all the way to Trantio and back, with only fighting to break the journey. If Lord Silvano has the urge to fight a righteous war, then why isn’t he going off to help in the march on Miragliano. The priests are always preaching that we live in Morr’s most cherished realm. Shouldn’t he be fighting the undead?”

“Oh, it’s too late for that,” said Aldus. “Duke Guidobaldo announced in his address that the war against the vampires is all but over. The enemy lost army after army trying to take on the Portomaggiorans and Remans, and now they’ve got the VMC against them too. All that’s left is the filthy job of cleaning up Miragliano, and I wouldn’t waste Pavonan lives on such nasty work. I reckon more’ll die of disease in such a wretched realm than in battle! If that war is over, then Lord Silvano obviously wants to make sure that the ratto uomo don’t gain an advantage while the living realms are weakened by the fight against the undead. Verminkind love ruinous places, and the north is one big ruin right now.”

“Not just the north,” said Giovacchino. “Pavona’s no better! All Boulderguts left us is the city and the southern side of the river. Astiano and Trantio are ruined too. Every realm hereabouts is as sickly and broken as the north.”

“Then praise the gods that our brave young lord is helping to quash the threat of ratmen before they grow too powerful.”

As the corporal spoke, he gestured to the street, for Lord Silvano himself, clad in brightly silvered armour and sporting a tall panache-crest of blue and white, his lance lowered as if to indicate his intention to advance, rode into view.

By the young lord’s side rode his knghtly standard bearer, and behind him rode the city’s young nobility, their shields decorated with Morr’s fleshless head, crowned as king of the gods.

“If you have the answer to everything, Aldus, then tell me this: Why didn’t the duke send Visconte Carjaval with the army instead of his only son and heir?”

“Oh, that was the plan. The Visconte had orders to that effect. But then the orders changed. You didn’t attend the temple this morning, did you?”

“My head still hurt from last night. Why? D’you think my soul’s in need of cleansing?”

“Ha! That and the rest of you!”

Giovacchino sniffed at his armpit, spilling some of the ale as he did so, then cursing.

“What about the temple?” he demanded. “Did you receive divine enlightenment? That’d explain all your answers.”

“The priest prayed for Lord Silvano’s success, then told us how the duke knew his son possessed a compassionate heart and a desire to serve the lawful gods, Morr Supreme above all, and that he yearned to defend the innocent, weak, the young and old, from all further upsets. Apparently, the duke even said his son was the better man than he, for where he had always taken rightful anger to bloody conclusion, his son was willing to temper his reactions with an urge to understand and forgive.”

Giovacchino frowned. “That doesn’t sound like the sort of thing the duke would say.”

“Maybe not, but that’s what the priest told us. And more than that, he said the duke had vowed to live ‘quiete and pacifice’ until his son’s safe return from victory.”

“Oh, that’s lovely,” said Giovacchino sarcastically. “It’s like poetry, ain’t it?” Then, more seriously, he asked. “Doesn’t sound like the duke either. Tell me though, is it true? Will the fighting end?”

Aldus shrugged. “I suppose if the Verezzan brigands stop what they’re doing, and everyone else leaves us alone for a while, then why not? Besides, the answer’s right in front of you. The army’s marching off. Say farewell to the young lord and our army.”

“Ha!” laughed Giovacchino. “And say hello to some peace and quiet.”

Padre

Lord

Crumbs! The pictures really don't work on a phone do they! Half the time you cannot even see the subject of the photo!! The technicalities are beyond me. It might even be my own phone settings for all I know! Sorry. (Edit) And now all the pictures have appeared properly for some strange reason. I can only apologise for my previous apology!

symphonicpoet

Moderator

Giovacchino reminds me a bit of Private Snafu. I suppose every military must have at least one such character or he wouldn't be such an effective trope. The Corporal seems a wise and decent fellow. I hope he lives to see the end of all this. Keep it coming Pardre!

Padre

Lord

Thanks Sympho!

I am still working the campaign 'at both ends"!

Part 10 of Tilea's Troubles is done, in which Prince Girenzo of Trantio plots against his rival, Duke Guidobaldo of Pavona.

https://youtu.be/ns-_0mULANY

I am, right now, working on scenery and figures (well, bits of figures - fiddly indeed!) for the next new story. Set in a marsh!

I am still working the campaign 'at both ends"!

Part 10 of Tilea's Troubles is done, in which Prince Girenzo of Trantio plots against his rival, Duke Guidobaldo of Pavona.

https://youtu.be/ns-_0mULANY

I am, right now, working on scenery and figures (well, bits of figures - fiddly indeed!) for the next new story. Set in a marsh!

symphonicpoet

Moderator

Ooh! A marsh! Will there be bog bodies? Possibly reanimated bog bodies?

"I met a lady in the meads.

Full beautiful a faerie's child.

Her hair was long and her foot was light

And her eyes were wild.

. . .

"I saw pale kings and princes too.

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all.

They cried - 'La Belle Dame Sans Merci

Hath thee in thrall!'"

Such stories are always so delightfully colorless! So splendidly wan!

. . . Wait, I was cheering against the vampire lords. I seem to have fallen into the wrong character. So sorry. Very much looking forward to the next installment!

"I met a lady in the meads.

Full beautiful a faerie's child.

Her hair was long and her foot was light

And her eyes were wild.

. . .

"I saw pale kings and princes too.

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all.

They cried - 'La Belle Dame Sans Merci

Hath thee in thrall!'"

Such stories are always so delightfully colorless! So splendidly wan!

. . . Wait, I was cheering against the vampire lords. I seem to have fallen into the wrong character. So sorry. Very much looking forward to the next installment!

Padre

Lord

The marsh story is really close to completed. In the meantime, part 11 of the video account of my campaign is complete. It is a battle story/report, in which victory was determined by whether or not the Duchess Maria could escape across the table!

https://youtu.be/HZQiSoXFW-o

https://youtu.be/HZQiSoXFW-o

symphonicpoet

Moderator

^It's a lot of fun to go back and revisit the early stages of your epic campaign and begin to learn just how everything developed. Oh, the good intentions!

Padre

Lord

Thanks Symphonic. Here is a piece concerning the campaign's 'present day'. (I think it actually helps me connect things up working from both ends simutaneously, gaining a perspective and occassionally remembering characters who can be brought back in, hopefully!)

...............................................

This to Reginaldo Scalise, Sindaco of the city of Portomaggiore, from Chimento Gagliardi, Chief Clerk to Lord Alessio Falconi.

My Lord Alessio has commanded me to inform you of the allied army’s current circumstances and condition. He wishes me to deliver a comprehensive account, for as his deputy in his beloved city, you must better understand the army’s requirements, the urgencies arising from our situation and the necessities of the daunting struggle before us. Furthermore, there is a task you must complete without delay.

We had rendezvoused with a brigade of the army of the VMC at Ebino, led by the Myrmiddian priestess Luccia La Fanciulla.

It was a force considerably weaker than that which was expected, and most disappointingly, lacking in guns, yet Lord Alessio was nevertheless undeterred. He ordered the entire allied army, including the Reman brigade under Captain Soldatovya’s command, consisting of mercenary dwarfs, crossbowmen and Reman bravi, to march along the dread road leading west towards Miragliano.

Our scouts reported that the watchtower of Soncino had been abandoned, which the army council took to mean that the enemy was aware of our approach and most likely drawing in its foul servants to concentrate his strength.

The army marched boldly to the watchtower’s vicinity and set about making an orderly and defensible camp.

As this work was accomplished, our scouts travelled further abroad to learn the villages of Leno were as quiet and empty as Soncino, having also been abandoned by the foe. The city of Miragliano itself, however, swarmed with the vampires’ servants, and its ancient, grey-stone walls hosted a force of rotting-but-walking corpses.

What most concerned the army council was the news that the putrid waters of the Blighted Marshes had been allowed to overspill their artificial bounds to claim the land around the city walls and, most likely, a good deal of the city within.

For several many years the dykes built to protect the city from the vast expanse of wetland to its immediate west have been left untended, so that now the once noble city seems to be sliding inexorably into the filthy waters. Even the road leading to the city has sunk beneath the mire, and the moat has merged with the wide expanse of stinking swamp stretching out for almost a mile in places, riddled with bloated corpses and bustling with clouds of filthy, fat flies. Miragliano is become, as indeed most of those in the army council had ominously anticipated, like a behemoth’s noisome corpse, washed up on the shore of a murky, accursed lake, infested with a host of maggots.

Lord Alessio spoke the plain truth when he said all this was only to be expected of a realm wracked by necromantic magics for so long. He ordered the army to march to the closest dry land to the city, there to build a strongly defensible camp …

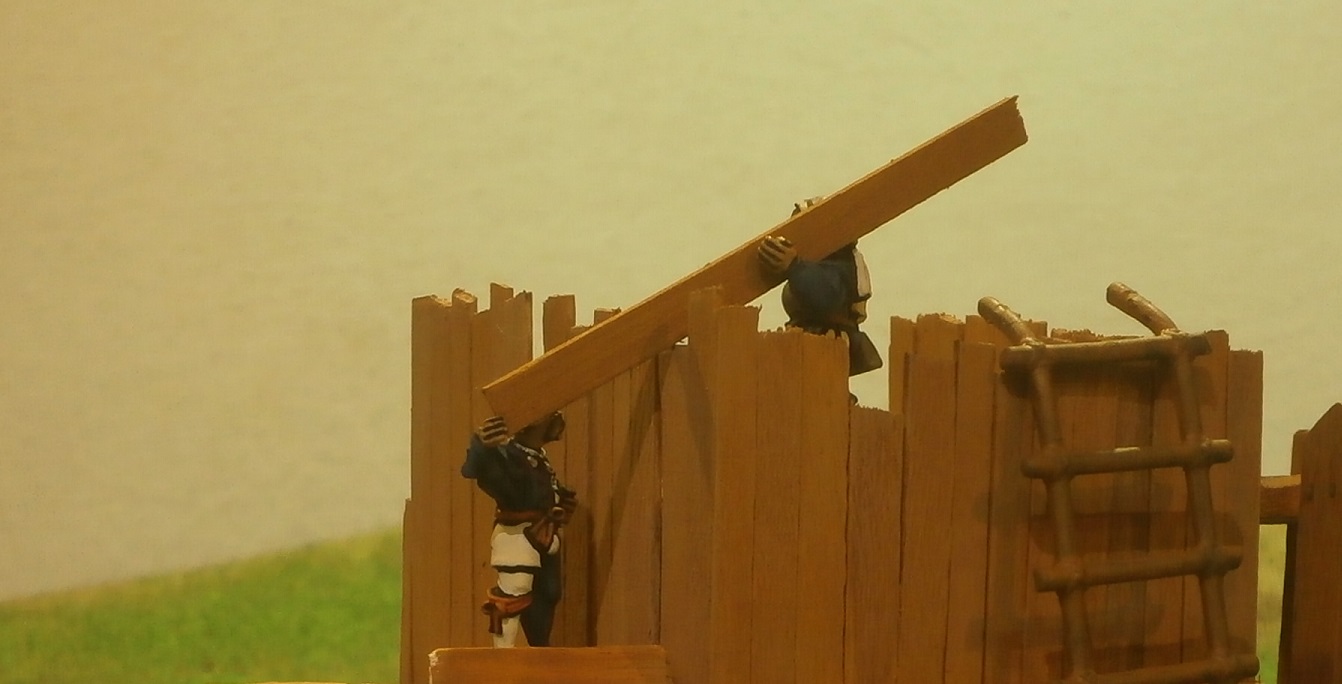

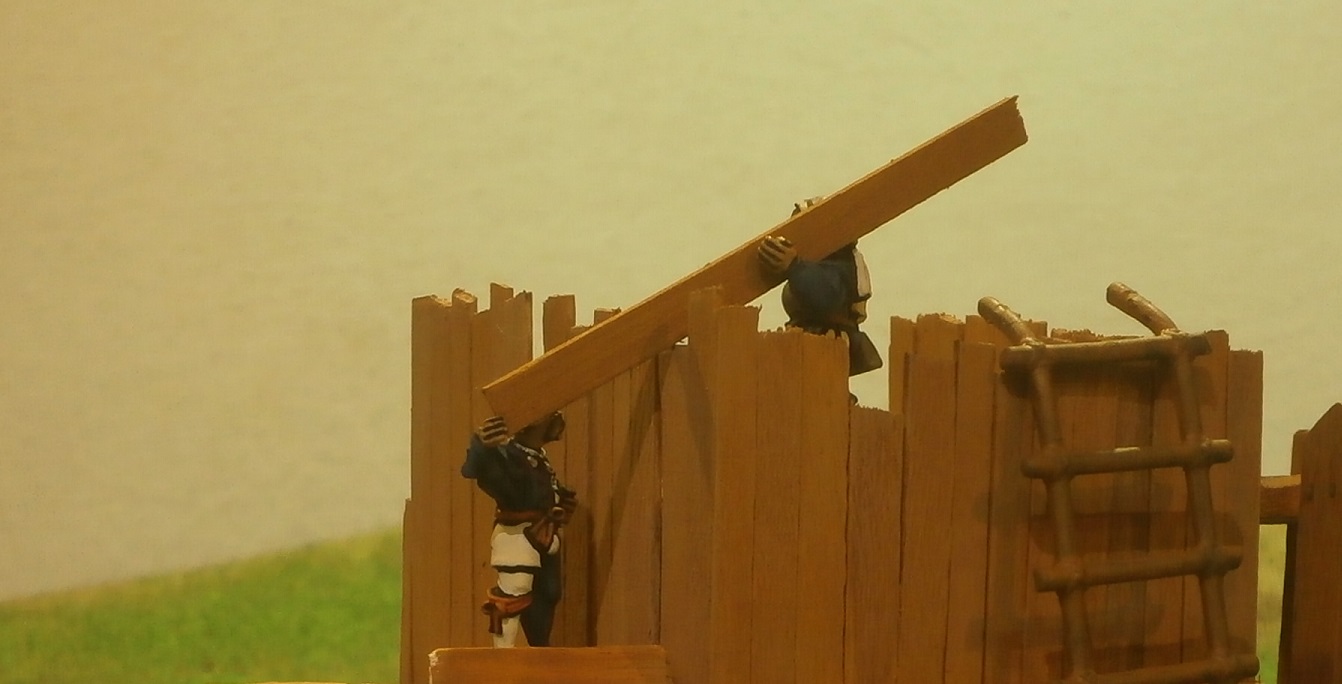

… and dispatched the scouts with orders to patrol orbitally about the camp to ensure nothing could approach unnoticed. The siege-master Guccio was instructed to begin work on siege towers and a ram able to approach the city walls. Meanwhile, a force drawn from both our army and that of the VMC should venture into the marshes there to clear out and burn the corpses, so that none remained to be re-animated by the foe in the oncoming assault.

Captain Guccio willingly took on his task and began pressing the men needed to better speed the work, from all three allied forces. Having questioned the scouts closely, he learned that the swamp may be crossable by foot soldiers, but only with great difficulty, thus it is he intends to mount the two towers and ram upon large rafts, which can then be poled, paddled or pushed to the walls, whichever proves feasible.

While Guggio’s men laboured to fell the necessary timber, much of the rest of the army set about not dissimilar work, building the camp on a large, relatively flat hill, about two miles from the city. Guards have been set in watches, ordered to maintain strict vigilance both day and night, with execution promised for any found to be derelict in this duty in any way whatsoever.

Having been here almost a week now, it has become evident that the enemy is in no rush to sally forth to give battle but seem content instead to lurk behind the city walls and the enveloping marsh. Whenever the wind, even but a breeze, blows from the direction of the city, the stench it carries is almost overwhelming, even for soldiers inured to the noisome airs of Ebino. Every day, soldiers bring the freshest water they can find to the camp, yet there is always corruption lurking in the taste of it, eliciting many a complaint. Our supplies of ale and wine are low, for we are now at such a great distance from the living realms, and there is a dearth of foraging opportunities within reach. Worse still, a considerable proportion of the supplies we brought with us - salted flesh-meat, cured fish, even the grain – has prematurely rotted. Perhaps inevitably, although still surprising considering how little time we have been here, a number of men have contracted a camp fever and their misery rings throughout the camp as they moan and thrash delirious upon their pallets!

The scouts have, so far, consistently reported that there is nothing out there. The land around us is truly dead. They know little concerning the marshes as it would be deadly for their horses to attempt to pass through such, so for several days we knew nothing concerning the areas closest the city and out to the south and west, where the marsh has overwhelmed the land. Until, that is, the clearing party returned from their attempted labours.

The VMC’s commander, Luccia La Fanciulla, acceded to Lord Alessio’s request to employ some of her troops for the cleansing of the marshland approaches. She ordered her mercenary ogres, under the command of a Captain Ogbut, as well as the wizard Serafina Rosa to join with the crossbowmen from both Remas and Portomaggiore, the latter commanded by Captain Lupo.

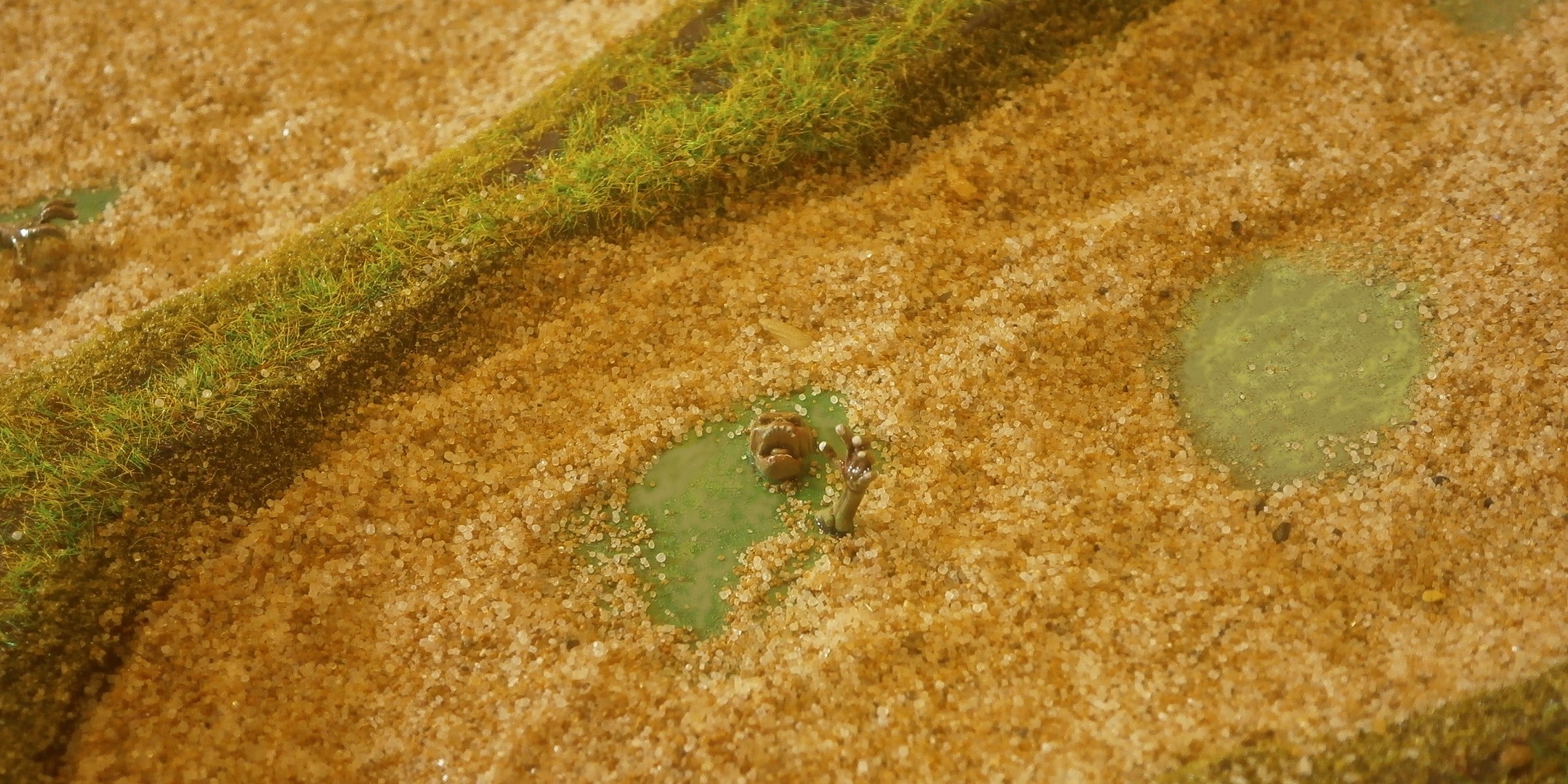

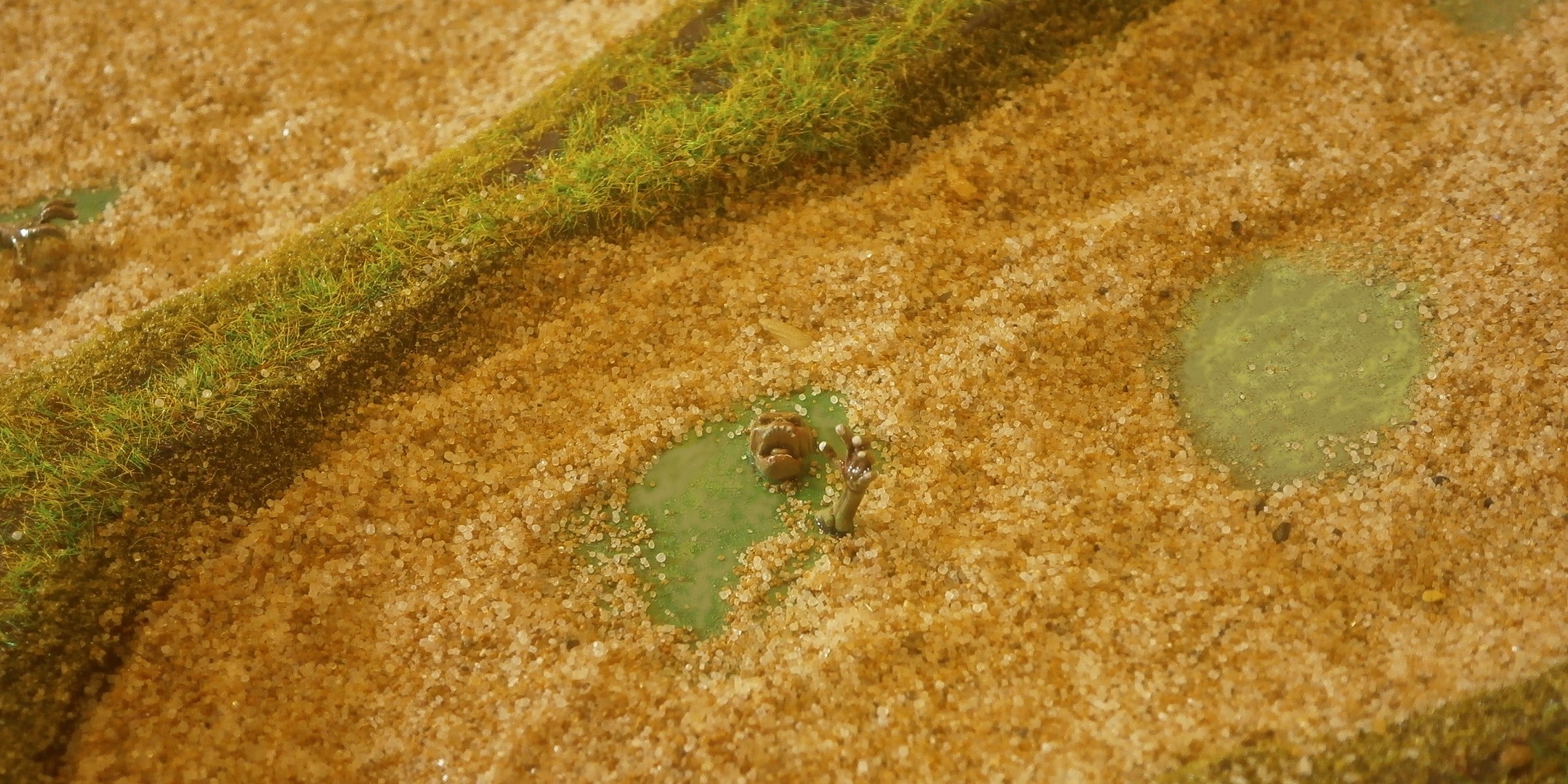

This force returned, however, after two days, reporting that they were entirely unable to complete their task, claiming that to do so was impossible, for not only did the marshes contain the dead, but hide the undead too. Concealed beneath the stagnant waters and quicksands, bloated and slimy zombies would suddenly reach up to clutch with a deathly grip at the legs of anyone attempting to pass through.

Several crossbowmen perished, dragged to their doom by an enemy that the others often could not even see, never mind kill. They had tried, shooting into the waters whenever they espied ripples, or the sudden appearance of a clutching, black-fingernailed hand, but learned quickly this was simply a waste of quarrels.

One of Ogbut’s ogres also perished …

… tripping in the undergrowth as he tried to reach a skeletal corpse, and so tumbled into quicksand …

… there to be grabbed and pulled down, head-first, to join with the undead below.

Half a dozen crossbowmen have apparently been frightened out of their wits, and to add to those who perished, half as many again have since succumbed to the sickness assailing the camp.

Before they left off their grisly, impossible labours, this same party discovered that the city’s moat has become an impassable stretch of noisome water, which merges with the marshland reaching out, passable but, as already revealed, dangerous, some way from the moat. The road to the city, despite becoming submerged, is wadable, like the swamp, and indeed possibly passable all the way to the gate. In answer to Lord Alessio’s query, the wizard Hakim agreed that his colossus could most likely use the road, very much doubting that any bloated zombies lurking beneath the waters could either slow or hurt it, but he immediately warned that there would be the risk of the brass, mechanically-magic giant straying from the road and succumbing to the marsh, becoming stuck or perhaps even sinking below the surface completely.

The siege master attempted to reassure the Lord General by reporting that he and his men were making good progress on the rafts, towers and ram, which should much more safely allow soldiers to reach the gate and walls, first by dragging and pushing, then by use of barge poles or oars, so that even the moat would prove no obstacle.

Lord Alessio accepted that Guccio’s ingenious moat bridges had had great success at Ebino, but stated that here there were many more difficulties to overcome, and that even should the rafts reach the gate and walls, it was unlikely that sufficient soldiers could be carried thereby to successfully overcome the defences. The rest, were they to follow by wading behind, might succumb to a multitude of dangers.

This is why Lord Alessio ordered that I write to you and to several other rulers and governors of the realms between here and Remas. He is thinking of a way in which our forces might be better enabled to reach the city. What he has I mind will require a great workforce, consisting of expendable labourers and not the soldiers needed for the assault.

You are commanded to empty the gaols and prisons directly of all able-bodied prisoners, including debtors and those awaiting either trial or execution, and to gather all sturdy vagrants and beggars (whether imprisoned or not), no less than 1,000 in number, and send them all here to us, under sufficient guard to ensure that none can abscond, by whatever means and route is the quickest. You shall inform them that they are to be employed upon essential and righteous work, and furthermore, that should they survive this reparative labour, they will be pardoned of all past misdemeanours, felonies, debts and wrongdoings of any kind. And if insufficient numbers are thus obtained, then you are also to press into service all common youths unengaged in either apprenticeship or gainful employment that they too might be dispatched to us forthwith, to serve as guastatori sappers, for which service they will be suitably rewarded at the completion of this campaign.

Make haste and obey these orders in full, for the fate of Tilea lies in the successful conclusion of this war against the vampires. They cannot be allowed to recover their strength, nor even lick their wounds, but must be exterminated completely as soon as possible.

...............................................

This to Reginaldo Scalise, Sindaco of the city of Portomaggiore, from Chimento Gagliardi, Chief Clerk to Lord Alessio Falconi.

My Lord Alessio has commanded me to inform you of the allied army’s current circumstances and condition. He wishes me to deliver a comprehensive account, for as his deputy in his beloved city, you must better understand the army’s requirements, the urgencies arising from our situation and the necessities of the daunting struggle before us. Furthermore, there is a task you must complete without delay.

We had rendezvoused with a brigade of the army of the VMC at Ebino, led by the Myrmiddian priestess Luccia La Fanciulla.

It was a force considerably weaker than that which was expected, and most disappointingly, lacking in guns, yet Lord Alessio was nevertheless undeterred. He ordered the entire allied army, including the Reman brigade under Captain Soldatovya’s command, consisting of mercenary dwarfs, crossbowmen and Reman bravi, to march along the dread road leading west towards Miragliano.

Our scouts reported that the watchtower of Soncino had been abandoned, which the army council took to mean that the enemy was aware of our approach and most likely drawing in its foul servants to concentrate his strength.

The army marched boldly to the watchtower’s vicinity and set about making an orderly and defensible camp.

As this work was accomplished, our scouts travelled further abroad to learn the villages of Leno were as quiet and empty as Soncino, having also been abandoned by the foe. The city of Miragliano itself, however, swarmed with the vampires’ servants, and its ancient, grey-stone walls hosted a force of rotting-but-walking corpses.

What most concerned the army council was the news that the putrid waters of the Blighted Marshes had been allowed to overspill their artificial bounds to claim the land around the city walls and, most likely, a good deal of the city within.

For several many years the dykes built to protect the city from the vast expanse of wetland to its immediate west have been left untended, so that now the once noble city seems to be sliding inexorably into the filthy waters. Even the road leading to the city has sunk beneath the mire, and the moat has merged with the wide expanse of stinking swamp stretching out for almost a mile in places, riddled with bloated corpses and bustling with clouds of filthy, fat flies. Miragliano is become, as indeed most of those in the army council had ominously anticipated, like a behemoth’s noisome corpse, washed up on the shore of a murky, accursed lake, infested with a host of maggots.

Lord Alessio spoke the plain truth when he said all this was only to be expected of a realm wracked by necromantic magics for so long. He ordered the army to march to the closest dry land to the city, there to build a strongly defensible camp …

… and dispatched the scouts with orders to patrol orbitally about the camp to ensure nothing could approach unnoticed. The siege-master Guccio was instructed to begin work on siege towers and a ram able to approach the city walls. Meanwhile, a force drawn from both our army and that of the VMC should venture into the marshes there to clear out and burn the corpses, so that none remained to be re-animated by the foe in the oncoming assault.

Captain Guccio willingly took on his task and began pressing the men needed to better speed the work, from all three allied forces. Having questioned the scouts closely, he learned that the swamp may be crossable by foot soldiers, but only with great difficulty, thus it is he intends to mount the two towers and ram upon large rafts, which can then be poled, paddled or pushed to the walls, whichever proves feasible.

While Guggio’s men laboured to fell the necessary timber, much of the rest of the army set about not dissimilar work, building the camp on a large, relatively flat hill, about two miles from the city. Guards have been set in watches, ordered to maintain strict vigilance both day and night, with execution promised for any found to be derelict in this duty in any way whatsoever.

Having been here almost a week now, it has become evident that the enemy is in no rush to sally forth to give battle but seem content instead to lurk behind the city walls and the enveloping marsh. Whenever the wind, even but a breeze, blows from the direction of the city, the stench it carries is almost overwhelming, even for soldiers inured to the noisome airs of Ebino. Every day, soldiers bring the freshest water they can find to the camp, yet there is always corruption lurking in the taste of it, eliciting many a complaint. Our supplies of ale and wine are low, for we are now at such a great distance from the living realms, and there is a dearth of foraging opportunities within reach. Worse still, a considerable proportion of the supplies we brought with us - salted flesh-meat, cured fish, even the grain – has prematurely rotted. Perhaps inevitably, although still surprising considering how little time we have been here, a number of men have contracted a camp fever and their misery rings throughout the camp as they moan and thrash delirious upon their pallets!

The scouts have, so far, consistently reported that there is nothing out there. The land around us is truly dead. They know little concerning the marshes as it would be deadly for their horses to attempt to pass through such, so for several days we knew nothing concerning the areas closest the city and out to the south and west, where the marsh has overwhelmed the land. Until, that is, the clearing party returned from their attempted labours.

The VMC’s commander, Luccia La Fanciulla, acceded to Lord Alessio’s request to employ some of her troops for the cleansing of the marshland approaches. She ordered her mercenary ogres, under the command of a Captain Ogbut, as well as the wizard Serafina Rosa to join with the crossbowmen from both Remas and Portomaggiore, the latter commanded by Captain Lupo.

This force returned, however, after two days, reporting that they were entirely unable to complete their task, claiming that to do so was impossible, for not only did the marshes contain the dead, but hide the undead too. Concealed beneath the stagnant waters and quicksands, bloated and slimy zombies would suddenly reach up to clutch with a deathly grip at the legs of anyone attempting to pass through.

Several crossbowmen perished, dragged to their doom by an enemy that the others often could not even see, never mind kill. They had tried, shooting into the waters whenever they espied ripples, or the sudden appearance of a clutching, black-fingernailed hand, but learned quickly this was simply a waste of quarrels.

One of Ogbut’s ogres also perished …

… tripping in the undergrowth as he tried to reach a skeletal corpse, and so tumbled into quicksand …

… there to be grabbed and pulled down, head-first, to join with the undead below.

Half a dozen crossbowmen have apparently been frightened out of their wits, and to add to those who perished, half as many again have since succumbed to the sickness assailing the camp.

Before they left off their grisly, impossible labours, this same party discovered that the city’s moat has become an impassable stretch of noisome water, which merges with the marshland reaching out, passable but, as already revealed, dangerous, some way from the moat. The road to the city, despite becoming submerged, is wadable, like the swamp, and indeed possibly passable all the way to the gate. In answer to Lord Alessio’s query, the wizard Hakim agreed that his colossus could most likely use the road, very much doubting that any bloated zombies lurking beneath the waters could either slow or hurt it, but he immediately warned that there would be the risk of the brass, mechanically-magic giant straying from the road and succumbing to the marsh, becoming stuck or perhaps even sinking below the surface completely.

The siege master attempted to reassure the Lord General by reporting that he and his men were making good progress on the rafts, towers and ram, which should much more safely allow soldiers to reach the gate and walls, first by dragging and pushing, then by use of barge poles or oars, so that even the moat would prove no obstacle.

Lord Alessio accepted that Guccio’s ingenious moat bridges had had great success at Ebino, but stated that here there were many more difficulties to overcome, and that even should the rafts reach the gate and walls, it was unlikely that sufficient soldiers could be carried thereby to successfully overcome the defences. The rest, were they to follow by wading behind, might succumb to a multitude of dangers.

This is why Lord Alessio ordered that I write to you and to several other rulers and governors of the realms between here and Remas. He is thinking of a way in which our forces might be better enabled to reach the city. What he has I mind will require a great workforce, consisting of expendable labourers and not the soldiers needed for the assault.

You are commanded to empty the gaols and prisons directly of all able-bodied prisoners, including debtors and those awaiting either trial or execution, and to gather all sturdy vagrants and beggars (whether imprisoned or not), no less than 1,000 in number, and send them all here to us, under sufficient guard to ensure that none can abscond, by whatever means and route is the quickest. You shall inform them that they are to be employed upon essential and righteous work, and furthermore, that should they survive this reparative labour, they will be pardoned of all past misdemeanours, felonies, debts and wrongdoings of any kind. And if insufficient numbers are thus obtained, then you are also to press into service all common youths unengaged in either apprenticeship or gainful employment that they too might be dispatched to us forthwith, to serve as guastatori sappers, for which service they will be suitably rewarded at the completion of this campaign.

Make haste and obey these orders in full, for the fate of Tilea lies in the successful conclusion of this war against the vampires. They cannot be allowed to recover their strength, nor even lick their wounds, but must be exterminated completely as soon as possible.

symphonicpoet

Moderator

^An assault on Miragliano! A short time ago such a thing would have been beyond imagining, but now it seems merely difficult. (Very difficult, to be sure.) Even should it succeed the dangers faced by the allies are many and deadly, but reclaiming Miragliano would be quite the blow indeed! Splendid stuff, Padre. Splendid!

Padre

Lord

And now back to the other end of the campaign! A new video. This one took longer to put together. I can't wait til I get to the stories which don't need all the pictures re-doing!

Part 12: https://youtu.be/r2bzYe_zUCg

Part 12: https://youtu.be/r2bzYe_zUCg

Padre

Lord

My campaign video part 13 is now completed. 'The Little Waagh', a battle report involving a wholly goblin force taking on professional and modern Marienburg soldiers. You might already see where this is going!

https://youtu.be/pkn6dlVycd4

Booglebor says: "Watch it. It's fun!"

https://youtu.be/pkn6dlVycd4

Booglebor says: "Watch it. It's fun!"

Padre

Lord

Part 14 of the video account of Tilea's troubles is up! See it at ...

https://youtu.be/bQdvhZT5S7Q

I am now going back (for a while) to the campaign's 'present day' - I have stories to write, games to arrange, figures to paint, not necessarily in that order.

https://youtu.be/bQdvhZT5S7Q

I am now going back (for a while) to the campaign's 'present day' - I have stories to write, games to arrange, figures to paint, not necessarily in that order.

symphonicpoet

Moderator

The YouTube reports are doing a nice job of catching me up on the early days of the campaign that I missed. Neat to see where this all camel from.

Padre

Lord

Thanks Symphonic. Should be doing another video this week, a short and (meant to be) funny.

Now back to 2404, the present day ...

Annihilation

South of Campogrotta, Summer 2404

First out had been the scouts, scurrying off in all directions to ascertain if it was safe for the rest of the army to emerge. They learned that the land immediately south of the river was only partially forested, with curving valleys through grassy sloped hills in between the scattered copses and larger woods. The forest proper began to the south, a little way off, which was where, they hoped, any sylvan elves would stay. Not that they were really scouting for elven forces, but rather to ensure the Campogrottan manthings were not present on this side of the river in any strength. They had also been ordered to slaughter any and all patrols they encountered, the ensure that word of the army’s presence did not pass back to Campogrotta too soon.

When enough scouts had returned to report no sightings – apart from a band of soldiers at the bridge leading to the city, several miles off, Seer-Lord Urlak Ashoscrochor himself, with some chieftains, clawleaders and his bodyguard regiment, had been the first of the army proper to leave the tunnel mouth. The scouts had already picked a route for the army, and what scouts had not returned were concealed at intervals along it, the better to spot any enemy approach and to carry the news back before an enemy got too close to the army.

Normally, when above ground, skaven would be expected to take the most concealed route, which would mean favouring the wooded stretches, but this was not to be the case on this occasion. Urlak had observed the annihilation bombard’s progress and knew that not only was its passage best facilitated by even ground and open spaces, but that it would likely prove catastrophically disastrous to move it through any other terrain. The engine’s attendants scurried ahead to remove rocks and fallen branches, fill holes and test the firmness of the ground, having become skilled in the art. But it would be impossible for them to clear away the tangled mass of undergrowth in the woods, never mind clearing roots and branches, in anything like sufficient time to allow the bombard’s continuous progress. It could never be allowed to stop for more than a few moments at a time, otherwise everything around it, even its protectively-gowned attendants, would wither and die. Nor could it be allowed to topple or crash, or even just jolt too hard, for then the grenado carried within might prematurely detonate. And so, despite all usual practice and the strong desire to lurk in the shadows, the bombard had to travel in the open, with the army moving necessarily ahead of it (for nothing could survive very long in its wake). That said, their route would at least favour the valley bottoms, with the hills providing at least some cover from prying eyes.

…

At Urlak’s request, the scouts led him to a hillside from which he would be able to watch the army embark upon the short journey. He had some decisions to make and had it in his head that it would be easier to make them if he could have a good look at the component parts of the large force at his disposal.

First to heave into view were the warriors of Clan Fiddlash’s ‘Red Jullgak’ Regiment. Armed with barbed spears and bearing round, iron-rimmed shields, they marched in good order, the sound of their hissing and snarling mingled with the clattering of their armour and gear, both louder than the noise their footfalls made upon the soft ground.

These warriors had already marched through the underpass far to the south of here, only to return without joining in battle, too late to join in the assault on Ravola. Unbloodied as they were, nevertheless, they seemed keen for a fight, and it was hard to imagine that any foe could withstand the charge of such a swarm of warriors.

Urlak’s chief scout was pointing at the regiment’s rear.

“Great and most noble lord,” hissed the scout, “See, see? How they push and shove? How even those at the back strain and strive to march on. They are eager-keen for the battle-fight, yes?”

And well they might be, thought Urlak. Fiddlash’s warriors had missed the looting of Ravola, instead marching almost non-stop in the underpass for many a week (on his orders). He had taken measures to ensure that few in his army knew just how dangerous the annihilation bombard was – especially to their own army, so the warriors must be assuming they would be ordered into battle soon. Their pent-up desire to fight could well be reaching fever-pitch. Or … perhaps the bombard’s potentially disastrous deadliness was no secret at all, and those at the regiment’s rear were pushing due to a desire to keep as far as possible from it. Everyone knew it poisoned the ground wherever it passed, but he had been hoping the otherwise ignorant masses had yet to realise just how much damage it would do if it were to miscarry in some way.

Urlak watched the warriors intently, for he had to decide which parts of his army to send ahead with the annihilation bombard. When it fired, hopefully bringing about the death of every single creature in Campogrotta, it had to be close enough to lob the grenade into the city. It would need guards to ensure it attained the required proximity, and not an insubstantial number, otherwise it could fail simply because an enemy patrol intercepted it.

He did not intend, however, to have his entire force, or even the greater part of it, close to the weapon when it fired, for if anything went wrong, he could lose quite literally everything. He had lived long enough to know that when it came to such experimental novelties, they should never be relied upon. Even the army’s tried and tested engines, used for many a century, were prone to catastrophic malfunctions, and indeed there was barely a warpstone weapon of any size, even as small as the jezzails, that could be fully trusted, such was the chaotic nature of the magically powerful, supralunary stone. Furthermore, the instability of the stone waxed in direct proportion to its potency. From what he had been told of the bombard, the grenado housed within its massive barrel contained possibly the most substantial and dense concentrations of powdered warpstone ever fashioned. If it was to misfire, then every living thing within a mile (or more) would likely become a fatality – which is exactly what it was supposed to do when it worked successfully, too, but at a location more conducive to harming the enemy.

While he had been pondering, the plague monks had passed, and then the lesser war machines had trundled by – some propelled by their own engines, others hauled by slaves. Bundles of jezzails and pavaises were strapped to several of them, a practise permitted by the engineers provided the jezzailers assisted, as required, to facilitate the engines’ passage. Such activity was rare enough that that jezzailers were happy to oblige in return for not having to lug their heavy weapons and shields on the march. Urlak knew some of the army’s lighter troops, such as the globadiers and giant rat swarms, were not moving in the line of march, but travelling on a parallel course, like outriders might in a manthings’ army, as a further precautionary measure against ambush.

By the time the slaves began to pass, he knew the bombard would be close. His commanders had planned the army’s order of march according to the importance of its regiments. The most valuable, the clan warriors, were at in the vanguard, whilst towards the rear, where the bombard was, were the more expendable regiments, including the slaves. This way, if the bombard were to be toppled by holes in the ground, strike a fallen tree, be struck itself by a tumbling boulder, or the ever-broiling grenade within it were simply to grow catastrophically hot, any of which could catalyse its premature explosion, then it would be the slaves who suffered most from the ensuing blast.

Even if the bombard suffered no fault, then mere proximity to its peculiarly poisonous ammunition was enough to sap the life from all forms of flora and fauna, and any unprotected skaven. It was therefore considered best, by all who had a say in the matter, that the slaves ought to be the ones to suffer the consequences of its deadly caress rather than anyone other part of the army. Of course, the protectively clothed warriors, the bombard’s attendants and guards, had to be close to it, but then they breathed filtered air and shielded their eyes with thick, tinted lenses.

Clan Fiddlash boasted a great many slaves, most of which were mustered as a fighting force. They passed by in ranks and files, escorted by whip wielding overseers to encourage the steadiness of their pace and the maintenance of their dressing.

It now occurred to Urlak that the overseers were unprotected, a notion that had not previously crossed his mind. He reassured himself with the thought that should the slaves’ masters succumb to the bombard’s poisonous proximity, then the slaves would surely be suffering exactly similarly, and thus unable to take advantage of their guards’ incapacity.

Urlak was pleased to see that none appeared to be in any way affected by the poison. He knew how useful such a horde of slaves could prove, and he would much rather they died serving his purpose in battle than perished simply moving from one place to another. They were not armed with spears, only short swords, giving the advantage to their whip-armed overseers. Any who had shown a hint of intransigence were chained, which would make their journey considerably more difficult. He noticed few were so chained, which boded well regarding their usefulness in battle. Of course, they did not possess shields, for that would make the whips a much less effective encouragement.

Studying the slaves, he pondered. Could they be trusted to form part of the bombard’s escort when it advanced to do its cruel work upon the city? Certainly, any force attempting to reach the war engine would struggle to make headway through such a mass of blade-wielding desperadoes.

But no - he had other tasks in mind for them. Should the bombard be successful in launching its deadly burden, the slaves would be the perfect choice to enter the city afterwards and ensure nothing had survived, as well as to fetch from it whatever treasures and goods could be salvaged. The warpstone poison harmed only living things, not precious metals and the like, and so there could well be good plunder to be had. Better to employ his more dispensable soldiers for such a task.

His musings were disturbed by the chief scout hissing, “Slave scum-filth!”

Urlak glanced at the scout.

“Forgive-forget, please-please, great lord. My words were unnecessary-unedifying.”

Urlak was not really listening and instead returned his attention to the slaves. They were led by what looked like a standard, and in a sense it was, but not one to show allegiance or to symbolize their honour or bravery, but rather solely to guide them – to indicate the direction and speed of their march and where exactly to form up whenever the command was given. Failure to do either resulted in the usual punishment.

On the hill behind Urlak were his best soldiers, his bodyguard regiment, the Yellow Hoods, who accompanied him at all times.

This regiment’s officers provided a useful source of intelligence for him, especially regarding the mood and disposition of the army. Despite the fact they almost always disagreed over some details, the very nature of their disagreement could itself assist Urlak in ascertaining the truth.

His bodyguard had fought very well at Ravola, never once leaving his side even when suffering heavy casualties from the enemy’s arrows and hurled rocks. He now wondered whether, as it had so proven its obedient loyalty, this was the regiment he should send ahead with the bombard?

Of all the regiments he commanded, this was the one he could trust most to follow the letter of his commands, and not to allow fear or caution to dilute their obedience. Yet, if he were to order them upon that task, they would not then be under his eyes, and who knew what weaknesses might manifest when they were bereft of his stern gaze? More importantly, if he did send them away, he himself would have no bodyguard, and that would not do at all.

Put simply, he did not trust either Clan Fiddlash or Clan Skravell anywhere near enough to risk being separated from his guards.

He turned to the nearest Yellow Hood clawleader …

… and asked,

“Where is the bombard? It ought and should be here now. Is it delayed? Is it stalled? What and why?”

“Noble leader, it comes. I feel and smell it, in the ground and on the wind-breeze.”

Moments later Urlak sensed it too. The clawleader had sharp senses, better than his own. Urlak would remember this, for it could prove useful in future.

“There, there, most high commander,” said the chief scout, pointing down the valley.

Before long the Clan Skryre warriors of the bombard’s guard regiment were below, the swish of their waxed linen and leather robes adding an extra sheen to the rattling sound of their passage. The bombard rolled behind, pushed by the mechanical wheel in which a new driver had to be placed almost every week, despite the several protective layers he wore!

Urlak could see the most senior ranking Skryre commander upon the guard regiment’s other flank, a warlock-engineer named Golchramik. He wore a mask about his upper face, and his eyes were covered by glass, but, unlike all the others, he had no muzzle-mask.

This intrigued Urlak. Was the engineer just careful, always staying ahead of the bombard? Or was he impervious to its poisonous aura, perhaps due to long exposure to similar warpstone effects? If the latter, then it did not bode well for the bombard’s effectiveness, for if this fellow could develop sufficient immunity to forego the wearing of a full mask, then could the grenado really be as deadly as Clan Skryre had promised? Perhaps the engineer was employing some other trick? It was not inconceivable that the substantial tank upon his back was plumbed into his throat or lungs, or that he employed subtle magics to counteract the poison. Urlak knew he was guessing, so decided not to consider the issue further. It mattered not.

The rest of those close to the bombard were much more comprehensively covered. Every warrior in the guard regiment wore a full mask, from the snout of which stretched a flexible, filter tube leading to an arrangement of tanks on their backs. There were several different kinds of mask, and an equally varied selection of tanks. Urlak wondered whether, after the engine’s firing, the proportioning of the survivors would reveal which combination was the most effective?

The warriors’ visibility must be restricted, he thought, for they saw the world through bulbous lenses of smoked glass fixed tightly in their leather masks. Whether this part-blindness would prove a perilous impediment was debatable, for if they were fighting near the bombard, whoever they faced would no doubt be seriously suffering (as did any unprotected creature) from its poisonous aura, which would surely more than even the odds. It seemed to Urlak that a more likely source of trouble was the proximity of their bared blades to the long filter tubes, especially when employed in the swish-swash of frenzied combat.

Squinting, he wondered whether this was the reason the tubes were so thick? It looked like the Skryre warriors had bound coarse cloth about them, perhaps hoping that a blade would cut only as deep as the binding and not all the way through to the tube within? Or perhaps, and this seemed more likely, the cloths were intended to seal (if only partially) any gashes and allow sufficient continued breathing until the tube could be properly patched?

Again, however, what did any of this matter? Right now, he needed to think like a warlord and not a tinkering engineer.

The obvious choices regarding to send ahead with the bombard where those warriors garbed in protective gear. Of course, the bombard’s attendants and crew must go, and its guard regiment should obviously accompany it, for they were the only substantial body of troops who could fight in close proximity to it without suffering.

But who and what else to send? The globadiers were similarly protected, and so they would be a sensible choice. As for the rest, he might send those he considered expendable, and if not the slaves, as he had already considered, then perhaps the Plague Monks, their numbers having been sorely diminished by the assault on Ravola? What was left of them could prove useful instead of simply perishing in amongst the multiple melees of a large battle?

Or should he send those that might prove useful to the bombard’s efficiency, such as the warlock engineers? They could assist in its movement and firing should its crew and assistants become casualties. And if he were to send the engineers, then why not send one or more of his army’s lesser engines of war? It could be a cunning ploy to order several machines ahead, for then the bombard would be less conspicuous, hidden ‘like among like’, and whatever enemies were encountered might be distracted by the other engines, no less massive than the bombard and indeed some of them more so. The enemy might thus attack entirely the wrong machines and waste what little time they had stop the bombard.

The bombard itself was chugging by below, three attendants on ether side of it. He chuckled for it looked almost comical, like a massive clockwork toy. Clatter-clatter, clunk-clunk it went. But then he saw how the grass behind it visibly withered then crumbled into powder moments after its passage, and the sight pushed all ideas that it was a toy from his mind.

Could it really destroy a city, and the army within? If so, how best to ensure it got close enough to do so?

He had until the evening to decide.

Now back to 2404, the present day ...

Annihilation

South of Campogrotta, Summer 2404

First out had been the scouts, scurrying off in all directions to ascertain if it was safe for the rest of the army to emerge. They learned that the land immediately south of the river was only partially forested, with curving valleys through grassy sloped hills in between the scattered copses and larger woods. The forest proper began to the south, a little way off, which was where, they hoped, any sylvan elves would stay. Not that they were really scouting for elven forces, but rather to ensure the Campogrottan manthings were not present on this side of the river in any strength. They had also been ordered to slaughter any and all patrols they encountered, the ensure that word of the army’s presence did not pass back to Campogrotta too soon.

When enough scouts had returned to report no sightings – apart from a band of soldiers at the bridge leading to the city, several miles off, Seer-Lord Urlak Ashoscrochor himself, with some chieftains, clawleaders and his bodyguard regiment, had been the first of the army proper to leave the tunnel mouth. The scouts had already picked a route for the army, and what scouts had not returned were concealed at intervals along it, the better to spot any enemy approach and to carry the news back before an enemy got too close to the army.

Normally, when above ground, skaven would be expected to take the most concealed route, which would mean favouring the wooded stretches, but this was not to be the case on this occasion. Urlak had observed the annihilation bombard’s progress and knew that not only was its passage best facilitated by even ground and open spaces, but that it would likely prove catastrophically disastrous to move it through any other terrain. The engine’s attendants scurried ahead to remove rocks and fallen branches, fill holes and test the firmness of the ground, having become skilled in the art. But it would be impossible for them to clear away the tangled mass of undergrowth in the woods, never mind clearing roots and branches, in anything like sufficient time to allow the bombard’s continuous progress. It could never be allowed to stop for more than a few moments at a time, otherwise everything around it, even its protectively-gowned attendants, would wither and die. Nor could it be allowed to topple or crash, or even just jolt too hard, for then the grenado carried within might prematurely detonate. And so, despite all usual practice and the strong desire to lurk in the shadows, the bombard had to travel in the open, with the army moving necessarily ahead of it (for nothing could survive very long in its wake). That said, their route would at least favour the valley bottoms, with the hills providing at least some cover from prying eyes.

…

At Urlak’s request, the scouts led him to a hillside from which he would be able to watch the army embark upon the short journey. He had some decisions to make and had it in his head that it would be easier to make them if he could have a good look at the component parts of the large force at his disposal.

First to heave into view were the warriors of Clan Fiddlash’s ‘Red Jullgak’ Regiment. Armed with barbed spears and bearing round, iron-rimmed shields, they marched in good order, the sound of their hissing and snarling mingled with the clattering of their armour and gear, both louder than the noise their footfalls made upon the soft ground.

These warriors had already marched through the underpass far to the south of here, only to return without joining in battle, too late to join in the assault on Ravola. Unbloodied as they were, nevertheless, they seemed keen for a fight, and it was hard to imagine that any foe could withstand the charge of such a swarm of warriors.

Urlak’s chief scout was pointing at the regiment’s rear.

“Great and most noble lord,” hissed the scout, “See, see? How they push and shove? How even those at the back strain and strive to march on. They are eager-keen for the battle-fight, yes?”

And well they might be, thought Urlak. Fiddlash’s warriors had missed the looting of Ravola, instead marching almost non-stop in the underpass for many a week (on his orders). He had taken measures to ensure that few in his army knew just how dangerous the annihilation bombard was – especially to their own army, so the warriors must be assuming they would be ordered into battle soon. Their pent-up desire to fight could well be reaching fever-pitch. Or … perhaps the bombard’s potentially disastrous deadliness was no secret at all, and those at the regiment’s rear were pushing due to a desire to keep as far as possible from it. Everyone knew it poisoned the ground wherever it passed, but he had been hoping the otherwise ignorant masses had yet to realise just how much damage it would do if it were to miscarry in some way.

Urlak watched the warriors intently, for he had to decide which parts of his army to send ahead with the annihilation bombard. When it fired, hopefully bringing about the death of every single creature in Campogrotta, it had to be close enough to lob the grenade into the city. It would need guards to ensure it attained the required proximity, and not an insubstantial number, otherwise it could fail simply because an enemy patrol intercepted it.

He did not intend, however, to have his entire force, or even the greater part of it, close to the weapon when it fired, for if anything went wrong, he could lose quite literally everything. He had lived long enough to know that when it came to such experimental novelties, they should never be relied upon. Even the army’s tried and tested engines, used for many a century, were prone to catastrophic malfunctions, and indeed there was barely a warpstone weapon of any size, even as small as the jezzails, that could be fully trusted, such was the chaotic nature of the magically powerful, supralunary stone. Furthermore, the instability of the stone waxed in direct proportion to its potency. From what he had been told of the bombard, the grenado housed within its massive barrel contained possibly the most substantial and dense concentrations of powdered warpstone ever fashioned. If it was to misfire, then every living thing within a mile (or more) would likely become a fatality – which is exactly what it was supposed to do when it worked successfully, too, but at a location more conducive to harming the enemy.

While he had been pondering, the plague monks had passed, and then the lesser war machines had trundled by – some propelled by their own engines, others hauled by slaves. Bundles of jezzails and pavaises were strapped to several of them, a practise permitted by the engineers provided the jezzailers assisted, as required, to facilitate the engines’ passage. Such activity was rare enough that that jezzailers were happy to oblige in return for not having to lug their heavy weapons and shields on the march. Urlak knew some of the army’s lighter troops, such as the globadiers and giant rat swarms, were not moving in the line of march, but travelling on a parallel course, like outriders might in a manthings’ army, as a further precautionary measure against ambush.

By the time the slaves began to pass, he knew the bombard would be close. His commanders had planned the army’s order of march according to the importance of its regiments. The most valuable, the clan warriors, were at in the vanguard, whilst towards the rear, where the bombard was, were the more expendable regiments, including the slaves. This way, if the bombard were to be toppled by holes in the ground, strike a fallen tree, be struck itself by a tumbling boulder, or the ever-broiling grenade within it were simply to grow catastrophically hot, any of which could catalyse its premature explosion, then it would be the slaves who suffered most from the ensuing blast.

Even if the bombard suffered no fault, then mere proximity to its peculiarly poisonous ammunition was enough to sap the life from all forms of flora and fauna, and any unprotected skaven. It was therefore considered best, by all who had a say in the matter, that the slaves ought to be the ones to suffer the consequences of its deadly caress rather than anyone other part of the army. Of course, the protectively clothed warriors, the bombard’s attendants and guards, had to be close to it, but then they breathed filtered air and shielded their eyes with thick, tinted lenses.

Clan Fiddlash boasted a great many slaves, most of which were mustered as a fighting force. They passed by in ranks and files, escorted by whip wielding overseers to encourage the steadiness of their pace and the maintenance of their dressing.

It now occurred to Urlak that the overseers were unprotected, a notion that had not previously crossed his mind. He reassured himself with the thought that should the slaves’ masters succumb to the bombard’s poisonous proximity, then the slaves would surely be suffering exactly similarly, and thus unable to take advantage of their guards’ incapacity.

Urlak was pleased to see that none appeared to be in any way affected by the poison. He knew how useful such a horde of slaves could prove, and he would much rather they died serving his purpose in battle than perished simply moving from one place to another. They were not armed with spears, only short swords, giving the advantage to their whip-armed overseers. Any who had shown a hint of intransigence were chained, which would make their journey considerably more difficult. He noticed few were so chained, which boded well regarding their usefulness in battle. Of course, they did not possess shields, for that would make the whips a much less effective encouragement.

Studying the slaves, he pondered. Could they be trusted to form part of the bombard’s escort when it advanced to do its cruel work upon the city? Certainly, any force attempting to reach the war engine would struggle to make headway through such a mass of blade-wielding desperadoes.

But no - he had other tasks in mind for them. Should the bombard be successful in launching its deadly burden, the slaves would be the perfect choice to enter the city afterwards and ensure nothing had survived, as well as to fetch from it whatever treasures and goods could be salvaged. The warpstone poison harmed only living things, not precious metals and the like, and so there could well be good plunder to be had. Better to employ his more dispensable soldiers for such a task.

His musings were disturbed by the chief scout hissing, “Slave scum-filth!”

Urlak glanced at the scout.

“Forgive-forget, please-please, great lord. My words were unnecessary-unedifying.”

Urlak was not really listening and instead returned his attention to the slaves. They were led by what looked like a standard, and in a sense it was, but not one to show allegiance or to symbolize their honour or bravery, but rather solely to guide them – to indicate the direction and speed of their march and where exactly to form up whenever the command was given. Failure to do either resulted in the usual punishment.

On the hill behind Urlak were his best soldiers, his bodyguard regiment, the Yellow Hoods, who accompanied him at all times.

This regiment’s officers provided a useful source of intelligence for him, especially regarding the mood and disposition of the army. Despite the fact they almost always disagreed over some details, the very nature of their disagreement could itself assist Urlak in ascertaining the truth.

His bodyguard had fought very well at Ravola, never once leaving his side even when suffering heavy casualties from the enemy’s arrows and hurled rocks. He now wondered whether, as it had so proven its obedient loyalty, this was the regiment he should send ahead with the bombard?

Of all the regiments he commanded, this was the one he could trust most to follow the letter of his commands, and not to allow fear or caution to dilute their obedience. Yet, if he were to order them upon that task, they would not then be under his eyes, and who knew what weaknesses might manifest when they were bereft of his stern gaze? More importantly, if he did send them away, he himself would have no bodyguard, and that would not do at all.

Put simply, he did not trust either Clan Fiddlash or Clan Skravell anywhere near enough to risk being separated from his guards.

He turned to the nearest Yellow Hood clawleader …

… and asked,

“Where is the bombard? It ought and should be here now. Is it delayed? Is it stalled? What and why?”