You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Tilea IC2401 (Campaign#8)

- Thread starter Padre

- Start date

.Grungni.

Serf

Padre I apologise I haven't returned with a list of the typos in you story I was collecting ... I am printing your story out to keep as a book that I can read away from my internet connection ... I think it brilliant and I hope that you continue ... I will share a story of my own with you in the future ... Kudos Padre!

Padre

Lord

Funny if you should ask if I was continuing the campaign. I finally rediscovered my mojo (I was somewhat distracted for a long while by the current world we live in!!!) and started GMing, painting, modelling, photographing and writing again. Here's the next story finished today and just an hour ago checked through by the skaven player to see if he liked it. He did!

...

Examples

Ravola, Spring 2404

Gradger sounded breathless when he arrived in the square, but this indicated nothing for certain as the wheezing function of his mask always made him sound so. He made his way immediately to the chattel overseer, Adragash.

“I have order-commands from the lord-master himself. You must obey prompt-quick. Yes, yes?”

Adragash’s lips parted to bare his teeth. He clutched a long whip as did all his helps, the handle of which he rested upon his shoulder so that the twisted hemp and wire cord hung down his back. Upon his head he had a leather cap with little iron cheek plates a-dangling at the sides, and in his other hand he carried a blade in the way in which one might carry a cane.

“Calm yourself,” Adragash hissed. “I always obey and never delay. You have no need to deliver such advice-warnings. Just-simply say what should and must be done, and it will be.”

Gradger now remembered how much he disliked the overseer. Admittedly, there were few skaven, if any, he did like, but there were gradations to his antipathy, from minor irritation to deep loathing, and Adragash was on the higher end of the scale. Still, this was the overseers’ domain, and all the skaven around were his to command, and so (as almost always) his dislike was something he had to make at least some effort to conceal.

“The chattel-slaves,” he said, pointing needlessly at the crowded cage that had been erected in the square, “they needs-must be prepared.”

Agradash did not move, nor did he speak, merely narrowed his eyes a little.

“Well,” said Gradger more loudly. “Prepare them!”

“I will do so, most keen and carefully. But you must speak-say more, Gradger-friend. For here they are, penned and patient, awaiting our command-orders. But what is the order? Are they to be fed? Moved? Made ready for labour-work? Speak-reveal exactly what the lord-master requires.”

Gradger was mentally lifting Adragash’s name up his list, to join those he despised the very most.

“They must be moved, made ready to be butchered if-when the order is given,” he said.

“Then they will be, I promise and assure,” answered the overseer. “But where to go? And how to kill?”

“They are to be made examples of, if necessary-needed” said Gradger. “Outside the city walls. I will show you where.”

“Examples ‘if necessary’? ‘If needed’?” said Adragash, in a curious tone. “How so? For whom? And why?”

“No question-talk is required. Only dutiful obeisance, yes?” said Gradger in a commanding manner.

“At least,” asked the overseer, “if nothing more, reveal-tell how they are to be butchered, so that preparations might be made for a suitable, satisfactory and swift execution of their execution.”

“Their corpses are to adorn-decorate the land around the city, to strike fright-fear into any foe that approaches.”

“Is this enemy expected or one that might merely perhaps come?” asked Adragash.

For a moment Gradger’s urge to appear important and informed got the better of him, and instead of again insisting on Adragash’s immediate action, he said,

“Manthing riders have been seen close-near to the city. Perhaps outrider-scouts for an army bringing aid-relief too late? If-when that army does arrive, they are to witness what is promised to be done to them, so they know terror-fear.”

“Grisly deaths and mangled corpses?” suggested Adragash.

“Yes, yes! They are to be stake-skewered and left to stink-rot,” said Gradger.

“Stakes, you say-speak,” said the overseer, his curious tone carrying a hint of sarcasm. “Stakes yet to be made?”

“Yes, yes. You must make them and you must place them. The soldiers have much else to do and are to be ever and always ready for battle.”

“The chattel-slaves will make their own stake-skewers,” said Adragash. “If necessary, if needed, then they will be put upon them. If not, then both stakes and chattel will further serve the lord-master howsoever we wish-desires.”

Momentarily satisfied that at last the order had been delivered and apparently accepted, Gradger looked over at the iron-railed pen. He was confused. It would be sufficient to hold meat animals like swine and goats, but surely, if they tried, the manthings could climb over? Then he noticed two of the overseers’ servants close the cage, and inside, a manthing lying prone, and he understood immediately what happened to those foolish enough to attempt to climb the iron railings - one sharp thrust of a halberd and the attempted escape would be ended.

Suddenly he noticed that most of the living chattel-slaves were looking not at the freshly fashioned corpse, but at him and Adragash.

“They stare and glare,” he said. “Those there and there, they are looking at us. They have defiance-rebellion left in them, yes, yes?”

Adragash grinned. “They do. Yet, Gradger friend, this is not so bad. What strength of will they harbour-possess reveals a strength left also in their bodies. That will be necessary-needed to cut, carry and carve well.”

Gradger was not convinced. One of the females had fixed her gaze upon him, and despite her lack of fangs and the absence of red in her eyes, he could clearly see her hate-anger. “If they have such resistance-rebellion left in them, then they will surely not make their own skewer stakes.”

“No, they will not. But when they are told to make stakes for a palisade meant to skewer-spit the enemy’s horses, and that if their work-labour is done fast-quick they will be allowed to eat, then they will have motive to work as well as the required strength.”

In that moment, despite his dislike of the overseer, Gadger understood why Adragash had been given command of the chattel-slaves.

...

Examples

Ravola, Spring 2404

Gradger sounded breathless when he arrived in the square, but this indicated nothing for certain as the wheezing function of his mask always made him sound so. He made his way immediately to the chattel overseer, Adragash.

“I have order-commands from the lord-master himself. You must obey prompt-quick. Yes, yes?”

Adragash’s lips parted to bare his teeth. He clutched a long whip as did all his helps, the handle of which he rested upon his shoulder so that the twisted hemp and wire cord hung down his back. Upon his head he had a leather cap with little iron cheek plates a-dangling at the sides, and in his other hand he carried a blade in the way in which one might carry a cane.

“Calm yourself,” Adragash hissed. “I always obey and never delay. You have no need to deliver such advice-warnings. Just-simply say what should and must be done, and it will be.”

Gradger now remembered how much he disliked the overseer. Admittedly, there were few skaven, if any, he did like, but there were gradations to his antipathy, from minor irritation to deep loathing, and Adragash was on the higher end of the scale. Still, this was the overseers’ domain, and all the skaven around were his to command, and so (as almost always) his dislike was something he had to make at least some effort to conceal.

“The chattel-slaves,” he said, pointing needlessly at the crowded cage that had been erected in the square, “they needs-must be prepared.”

Agradash did not move, nor did he speak, merely narrowed his eyes a little.

“Well,” said Gradger more loudly. “Prepare them!”

“I will do so, most keen and carefully. But you must speak-say more, Gradger-friend. For here they are, penned and patient, awaiting our command-orders. But what is the order? Are they to be fed? Moved? Made ready for labour-work? Speak-reveal exactly what the lord-master requires.”

Gradger was mentally lifting Adragash’s name up his list, to join those he despised the very most.

“They must be moved, made ready to be butchered if-when the order is given,” he said.

“Then they will be, I promise and assure,” answered the overseer. “But where to go? And how to kill?”

“They are to be made examples of, if necessary-needed” said Gradger. “Outside the city walls. I will show you where.”

“Examples ‘if necessary’? ‘If needed’?” said Adragash, in a curious tone. “How so? For whom? And why?”

“No question-talk is required. Only dutiful obeisance, yes?” said Gradger in a commanding manner.

“At least,” asked the overseer, “if nothing more, reveal-tell how they are to be butchered, so that preparations might be made for a suitable, satisfactory and swift execution of their execution.”

“Their corpses are to adorn-decorate the land around the city, to strike fright-fear into any foe that approaches.”

“Is this enemy expected or one that might merely perhaps come?” asked Adragash.

For a moment Gradger’s urge to appear important and informed got the better of him, and instead of again insisting on Adragash’s immediate action, he said,

“Manthing riders have been seen close-near to the city. Perhaps outrider-scouts for an army bringing aid-relief too late? If-when that army does arrive, they are to witness what is promised to be done to them, so they know terror-fear.”

“Grisly deaths and mangled corpses?” suggested Adragash.

“Yes, yes! They are to be stake-skewered and left to stink-rot,” said Gradger.

“Stakes, you say-speak,” said the overseer, his curious tone carrying a hint of sarcasm. “Stakes yet to be made?”

“Yes, yes. You must make them and you must place them. The soldiers have much else to do and are to be ever and always ready for battle.”

“The chattel-slaves will make their own stake-skewers,” said Adragash. “If necessary, if needed, then they will be put upon them. If not, then both stakes and chattel will further serve the lord-master howsoever we wish-desires.”

Momentarily satisfied that at last the order had been delivered and apparently accepted, Gradger looked over at the iron-railed pen. He was confused. It would be sufficient to hold meat animals like swine and goats, but surely, if they tried, the manthings could climb over? Then he noticed two of the overseers’ servants close the cage, and inside, a manthing lying prone, and he understood immediately what happened to those foolish enough to attempt to climb the iron railings - one sharp thrust of a halberd and the attempted escape would be ended.

Suddenly he noticed that most of the living chattel-slaves were looking not at the freshly fashioned corpse, but at him and Adragash.

“They stare and glare,” he said. “Those there and there, they are looking at us. They have defiance-rebellion left in them, yes, yes?”

Adragash grinned. “They do. Yet, Gradger friend, this is not so bad. What strength of will they harbour-possess reveals a strength left also in their bodies. That will be necessary-needed to cut, carry and carve well.”

Gradger was not convinced. One of the females had fixed her gaze upon him, and despite her lack of fangs and the absence of red in her eyes, he could clearly see her hate-anger. “If they have such resistance-rebellion left in them, then they will surely not make their own skewer stakes.”

“No, they will not. But when they are told to make stakes for a palisade meant to skewer-spit the enemy’s horses, and that if their work-labour is done fast-quick they will be allowed to eat, then they will have motive to work as well as the required strength.”

In that moment, despite his dislike of the overseer, Gadger understood why Adragash had been given command of the chattel-slaves.

Lands Annex

Vassal

Superb as always!

Hope you have a good festive season!

Hope you have a good festive season!

symphonicpoet

Moderator

Delightful and terrifying Padre. As always.  I understand that this plague has been a bale to us all, but the year of the rat will pass soon and with luck the ox will treat us better. Let us work-prepare for a new game-contest.

I understand that this plague has been a bale to us all, but the year of the rat will pass soon and with luck the ox will treat us better. Let us work-prepare for a new game-contest.

Be well, Padre. And thank you for this.

Be well, Padre. And thank you for this.

Padre

Lord

Thanks, Symphonic and Lands! I hope you two can extract some merriment out of the holidays too!

I wanted to get this next story out of the way so that I can then get the GMinng out of the way and maybe even run a play by-e-mail battle over the holidays.

This one, deceptively simple, was an ambitious one to put together. Hope you all like it.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Some Too Late and One Too Early

Northern Tilea, Spring 2404

They made their way along the lesser-known paths in the woods, some of which were so well hidden that they had to push their way through the undergrowth to access them. Their new friends asked them not to cut the branches as they did so. Once they were on the secret sylvan byways, however, they were able to ride at a pace. Captain Gesualdi had informed Perrette that some of the paths, the wider and more level ones, were the remains of ancient roads from the time when Remas ruled the entire peninsula and many lands beyond. The stonework had long since sunk beneath the ground, but for considerable stretches there was a surprising lack of trees, even saplings, to hinder them. She began to suspect this was not by chance, and that their new companions had a hand in ensuring these passageways remained relatively clear, all the better to enable speedy, secretive forays.

Having met their new friends a week ago, Perette and the last of her Brabanzon had spent most of the intervening time searching for any other comrades who had escaped the assault on Ravola, with some success. She now had with her most of the company’s riders, a small band of archers and a handful of the camp followers. She was afraid that no-one else had escaped. They had failed to find even one of the young baron’s retinue of knights. It pained her to think of the poor souls she and the baron had led to the city, and all the others who came there when told it was safe to return now that the ogres were gone. A surprising number had come out of hiding, bedraggled and thin, like wilderness hermits on the edge of starvation. All these were now most likely suffering cruelties at the ratmen’s clawed hands. Horrifying as the thought was, it occurred to her that perhaps the best they could hope for was a quick death, being butchered for their flesh. During the fight she had seen several monstrous creatures amongst the enemy’s number that bore horrible scars and blemishes, with patches of iron somehow riveted onto their very skin, even piercings to allow intestine-like tubes to penetrate their bodies! If they could do that to their own kind, what might they do to prisoners? Better death than such mutilation.

Every night since the flight she had slept badly, even when her new friends had offered her relative safety. She would toss and turn for two hours or so as her mind raced, considering what she could and should have done different, and when she finally slipped into brief, fretful sleep she dreamt only of the battle. She had come to Tilea expecting to face ogres, ostensibly to assist in the reclamation of a realm for a less cruel master and to save what poor souls had been enslaved by the brutes. When that work had been done, however, she had first learned that vampires were also ravaging great swathes of Tilea, and had then, only weeks after ridding Ravola of ogres, been driven from the city by an army of ratmen. This land had been cursed thrice over!

Although it was less than a year ago, it felt like a decade since Perrette had departed Bretonnia. When she set off to cross the high pass into Tilea, she merely wanted to escape Bretonnia, to put her old life behind her and find a new, hopefully better one. Joyously carousing with the Brabanzon one raucous night she found them to be better company than either peasants or noblemen, and not at all as uncouth and callous as one might expect of such a mercenary band. Indeed, she had discovered that the Brabanzon, at least those there that night, possessed an unexpected yet welcome decency, however deeply concealed beneath their swaggering bravado, cruel jests and coarse language. When they told her they were employed to travel to Tilea she had not hesitated in choosing to go with them, despite having no contract herself. Leaving Bretonnia as little better than a camp follower, since the second assault on Campogrotta (and by the Brabanzon’s own choosing) she had come to command the whole company. At least, what was left of it now.

The Brabanzon’s new allies were a mysterious bunch, whose number she had yet to estimate, nor had she ascertained who truly commanded them. The particular band they travelled with had a leader, being the burly Captain Valfrido Gesualdi, but although he had said nothing concerning the matter, something told her that he served another. The name they called themselves – the Arrabbiati, or ‘Angry Ones’ – she had heard during her brief time in Campogrotta when one of the city’s inhabitants had asked her if the reason the Arrabbiati were not amongst the army was because the dwarfs refused to accept their help. During the short conversation that followed she had learned that during the Campogrottans’ time as slaves of Boulderguts’ ogres there had been several incidents of sabotage and assassination against the brutes and it had been generally believed that the Arrabbiati had been behind the deeds. For more than a decade, the brigand band had earned a reputation amongst the common, labouring folk for robbing the most arrogant and tyrannical of the nobility and the greediest of the merchant families – leaving nothing behind but bodies and whichever of their red-fletched arrows had snapped. What with Boulderguts being the very worst of tyrants, his man-eating brutes the most merciless of oppressors, then surely, said her informant, the Arrabbiati would target them? Although at the time she thought it sounded like wishful thinking, it seemed likely that for want of anyone else to rob a band of outlaws might be forced to rob instead from the ogres. Later she learned that they might indeed possess some truly noble motivations, for it was said they been decimated when they had ridden out of nothing but love for the Duchess Maria (regarded as an enlightened and fair ruler, before she became a vampire) to assist in the fight against the vampire Duke Alessandro’s army.

A broad-shouldered man, with a chin as wide as his cheeks, Captain Gesualdi was armed with a bow like the rest of his men but had a scarf about his head instead of a helmet. Like his entire company, he wore dark clothes - his tunic being a dull shade of purple, his scarf burgundy.

Back in Campogrotta Perrette heard one inhabitant refer to the Arrabiatti as the Brotherhood of the Shadows, and it seemed they were indeed suitably dressed to lurk unseen during their nocturnal and crepuscular activities. Some of their horses, however, were white, so either they only hid in shadows when creeping about on foot, or the habit was an affectation to suit their reputation, or, and this surely was most likely, they were loath to waste good horses when they got them.

Their standard was that of a wolfshead, argent upon a sanguine field.

Their modus operandi indicated that this was not a wolf like the white one of Middenland – the forever brawling, bloody, winter wolf of Ulric. Instead, this was a hungry wolf, carefully choosing which prey to stalk and howling at the moon when there were none for miles to hear. The Arrabiatti disparagingly called it the mutt. When the mutt was mounted, they all had to make ready to move. Twice now she had heard them say, ‘Meet at the mutt’, an action made all the easier by the fact that the company’s horn blower always travelled with their standard bearer. Of course, the horn had a sound like a wolf howling.

Now Perette had met them, they seemed so far to warrant their heroic reputation. ‘Goodfellows all,’ they had called themselves at their first encounter, and they did not hesitate to help her and the fleeing Brabanzon. They had offered victuals and shelter, then assisted in the finding of the other Brabanzon survivors. Now they were guiding them by way of these obscure paths away from the city to put them safely on the road back to Campogrotta. In return, they had asked for nothing - at least, not yet. Her own Brabanzon would also have found it in them to help strangers in need, but the matter of remuneration would definitely have been broached long before now! Captain Gesualdi had even gifted her a coat of scale armour which he said would not interfere with her magics for it had once been the property of a wizard. When she asked how it had come into his possession, he answered with a grin that she should not look a gift horse in the mouth.

Three days before, with surely little prospect of profit from a city that had nothing of value left in it when they arrived, and with even less now that the ratmen had infested and consumed it, the captain had dispatched several of his men to scout much closer to the city, out of concern that the ratmen might be preparing to march from the city. She offered some of her own soldiers to accompany the Arrabbiati scouts, for they had recent knowledge of the lay of the land, but Gesualdi had insisted that his men knew the area like the ‘back of their hands’ and that the Brabanzon would do better to scout ahead as they made their way south, searching for any last remaining escapees wandering the wilds.

Perette’s second in command, Osmont, rode much of the way beside her. The riders had previously been commanded by a Sergeant Huget, but he was missing in action, believed to have been shot from his horse by one of the enemy’s long-barrelled muskets before getting out of sight of Ravola’s walls. The man who reported this had died of his wounds only minutes after imparting the news, and so none could now ask him if he was certain! Even if Huget turned up, however, Perrette would keep Osmont as her second, which would put him in command of the riders.

Osmont had an easy relationship with her, often joking - doing so whenever he thought she needed such to lift her spirits but falling quiet when she had a need for sombre contemplation. He had been there in the typpling room of the inn when she first met the company and from the start he seemed to see something in her that she herself had not really been aware of. He was also quite protective. On two occasions, including that first night, he had, with the slightest shake of his head, subtly signalled that the man she was getting close to was not someone she should favour! A veteran of many a war, or at least, many a bloody squabble between this baron and that marquis, he had a calm confidence about him, and a watchfulness. During the fall of Ravola it was he who had understood it was time to leave – not in the sense of being panicked into fleeing, but rather in assessing the situation and recognising that they were beaten.

…

Early in the afternoon a cry was heard from the column of riders behind.

“Ho! Riders! To the left.”

At first, Perrette could see nothing but trees, but then she caught a flashing glimpse of something in motion through the foliage.

“It’s Iginio!” came the same voice again.

“That it is!” came an answering cry. A few moments later the three Arrabiatti scouts emerged from a smaller path which joined the main group’s own route like a tributary stream might merge with a river.

The chief scout, Iginio, wore a dark cloak like many of his comrades and rode a chestnut mount. He came right up to the front of the column to ride beside Perrette and Captain Gesualdi.

“Good captain, my lady, well met!” he said by way of greeting.

“Glad to see you back, Iginio,” said the captain. “Did you get close to the city? The enemy?”

“And the people? What about them?” added Perrette.

“We got close, captain,” said the scout. “Close enough for some of the ratmen to espy us, which is when we left. Apart from a few poor wretches, no more than a dozen, shifting stones under guard where a tower has collapsed, we saw no other people, my lady. There was acrid smoke coming from within, the stink of burning hair and flesh. They must have been burning either beasts or people.”

“Is their entire force still present?” asked the captain.

“Aye, I reckon it is,” said Iginio. Then he addressed Perrette directly. “My lady, you told us they had no war machines?”

“None,” said Perrette. “They took the walls by weight of numbers and had just enough to do so. We battered them badly, killing so many, yet still they came. I pray to all the gods it was their fur you smelled burning.”

“I wish I could affirm that. What I can report is that they do have machines now.”

“They must have lagged behind on their march,” suggested the captain. “Which means they attacked before their full force was mustered, before they had that which could shoot upon the walls.”

“Perhaps arrogance convinced them they would win?” said Perrette. “And that we would not prove a troublesome foe.”

“If so, they learned their lesson, my lady,” said the captain. “From all accounts you put them to far more trouble than an equal number of any other soldiers could have done. The ratmen are bullies, cruel and cunning. They do possess a species of arrogance, for they think they are the only creatures worthy of living in the world. But they are not brave. They rely on strength of numbers in battle, and on terrible machines that can conjure lightning itself. They first bombard their foes, then quickly swarm to overwhelm them before they can recover. There must have been a pressing reason for their haste. It’s likely they were worried you were soon to be reinforced.”

“We did send for help, from Campogrotta. But they attacked long before our messengers could possibly have arrived.”

“My lady, help was sent,” said the scout. “We met with a force from Campogrotta, both heavy and light horsemen, and even some dwarfs following them, catching up every night to sleep for half the time the men did.”

“Compagnia del Sole soldiers?” asked Perrette.

“Aye, my lady, they were. Dispatched from Campogrotta to relieve Ravola but arriving four days too late. They’d scouted the enemy too and were about to return.”

This made little sense to Perrette. Neither the messengers she sent to Campogrotta nor any force of mounted men at arms and dwarfs could possibly have travelled fast enough. The distance was too great. She knew because she had made the journey herself. Even on secret paths such as these for part of the way, it could not be done. Which meant the Compagnia soldiers must have set off long before her messengers arrived. Then it occurred to her – perhaps the soldiers were already on their way for some other reason, and they met her messengers part way?

“Master scout,” she asked. “When you spoke to them, did they say they were ordered from Campogrotta to ride to Ravola’s relief?”

“Yes, my lady. Someone from Ravola came to them and begged that the whole Compagnia go north to your aid. Their captain general sent the riders and dwarfs ahead to learn what they could. They claimed not to know if the commander was following with the rest of the army.”

Perrette held her tongue, but what the man was saying was impossible. Apparently Osmont had not considered the mathematics of the claim, for he asked,

“Master scout, the dwarfs – did you meet with them?”

“Not to speak to. Their commander, I think, was named Greyfury.”

Osmont laughed which made the others look. “He could not bear to be parted from his true love,” he said.

While the others wondered what he could mean, Perette just rolled her eyes and gave Osmont a look meant to silence him. She did not think these men were currently in the mood to entertain private jests. Almost as if she were precognitive, the scout Iginio’s tone changed.

“There was something else we saw. Strange indeed, if truth be told. When we drew close to the city we passed over a long patch of poisoned ground, where all the plants had withered as if baked by a hot sun for many days.”

“We could plainly see no animals had trespassed upon it. There were tracks passing along it, as if left by three large wagons. They had crushed some small trees while brushing past others, so that their blackened remnants still remained erect but sagging. Our mounts became fearful, acting most contrary and we ourselves felt a sudden imbalance in our humours …”

“We did not linger. I don’t think we could have done if we tried. Saladino’s stomach ain’t been right since. We went over it and on, thinking that some poisonous ratman taint must have been released there, a magical curse cast by something on the wagon or some spillage of aqua fortis or the like. Perhaps the ratmen spread corruption from the wagons, as if scattering the very opposite of seeds - sowing death instead of new life? After spying upon the city walls, we chose a different path back, all the better to learn as much as we could of the enemy’s disposition, but mostly to avoid the tainted ground. Yet we again encountered an exactly similar strip of corruption! Loathe to cross it, men and mounts alike, we thought to skirt around it this time. But there was no going around, for the poisoned land proved to be like unto a path, which stretched all the way at least to the first place we had crossed.”

Iginio fell momentarily silent, while the others just waited to hear what else he said.

“I cannot say for certain, but the dead path looked to follow a curved course around the city. We were unable to discover if this was true, for to linger so close to the enemy would surely have meant we were attacked, and to travel any length of time even just beside the corruption may have meant we became too ill to return. But, before we crossed back over, I reckon we got the measure of it. I’d lay all the gold I have that it goes around the entire city.”

“Some sort of magical barrier, perhaps, meant to prevent approach?” suggested Perrette.

“I think not, my lady, for we crossed it twice, there and back again, howsoever loath we were to do so the second time. I doubt anyone could travel along the length of it for more than an hour, yet crossing it takes only a few moments and so is bearable.”

Perrette now noticed the darkness around Iginio’s eyes. She saw too that his horse was sweating noticeably more than her own or the captain’s mount.

“You were exceeding brave to do so,” she said. “And all that you learned of the ratmen, the poor inhabitants and the poisoned band could prove vital to our plans.”

“Iginio,” asked the captain, “how long did you linger in that poisoned place?”

“When we first crossed, just enough time to dismount and look closely at the ground, to notice that the wagons that passed seemed to have differently sized wheels, and some very large, and that they apparently not hauled by draught animals, but of course we could have worked that out without noticing the lack of prints. When we crossed back, we wasted not a moment’s time in getting to the other side.”

“I don’t think it likely they were wagons, but rather some sort of war engines,” said Osmont. “Probably came up with the others you did see. Perhaps they were like giant censers, emitting a cloud of noxious, noisome vapour, which they intend to push at the enemy in battle? As to why they travelled round the city, I know not. Seems a great waste of effort to me just to kill a few trees and weeds.”

“We shall have to take a look at whatever made the dead path,” mused the Arrabiatti captain. “Perhaps then we will learn its true nature and purpose? In the meantime, if your friends the Compagnia soldiers are making their way back to Campogrotta, then we should take you to them.”

“They are not far away, captain,” said the chief scout. “Only two hour’s ride, I reckon.”

“But don’t they have a head start on us?” said Perrette.

“They do, my lady,” agreed the scout. “But they do not know the paths as well as us, and they travel with a long journey in mind, at a pace they can maintain, while we can make a dash to catch up with them.”

…

…

Two hour’s later the riders descended from a high path and rode out towards the even higher hills between them and Campogrotta. Ahead of them, where their present path met with another, they could see a company of horsemen.

Their banner bore the white baton and half-sun emblem of the Compagnia del Sole. They looked surprised at first …

… but Perrette urged her horse out beyond the body, knowing that the soldiers would recall her from Campogrotta. Indeed, the fellow at their fore had drunkenly tried to woo her the night before she left for Ravola!

I wanted to get this next story out of the way so that I can then get the GMinng out of the way and maybe even run a play by-e-mail battle over the holidays.

This one, deceptively simple, was an ambitious one to put together. Hope you all like it.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Some Too Late and One Too Early

Northern Tilea, Spring 2404

They made their way along the lesser-known paths in the woods, some of which were so well hidden that they had to push their way through the undergrowth to access them. Their new friends asked them not to cut the branches as they did so. Once they were on the secret sylvan byways, however, they were able to ride at a pace. Captain Gesualdi had informed Perrette that some of the paths, the wider and more level ones, were the remains of ancient roads from the time when Remas ruled the entire peninsula and many lands beyond. The stonework had long since sunk beneath the ground, but for considerable stretches there was a surprising lack of trees, even saplings, to hinder them. She began to suspect this was not by chance, and that their new companions had a hand in ensuring these passageways remained relatively clear, all the better to enable speedy, secretive forays.

Having met their new friends a week ago, Perette and the last of her Brabanzon had spent most of the intervening time searching for any other comrades who had escaped the assault on Ravola, with some success. She now had with her most of the company’s riders, a small band of archers and a handful of the camp followers. She was afraid that no-one else had escaped. They had failed to find even one of the young baron’s retinue of knights. It pained her to think of the poor souls she and the baron had led to the city, and all the others who came there when told it was safe to return now that the ogres were gone. A surprising number had come out of hiding, bedraggled and thin, like wilderness hermits on the edge of starvation. All these were now most likely suffering cruelties at the ratmen’s clawed hands. Horrifying as the thought was, it occurred to her that perhaps the best they could hope for was a quick death, being butchered for their flesh. During the fight she had seen several monstrous creatures amongst the enemy’s number that bore horrible scars and blemishes, with patches of iron somehow riveted onto their very skin, even piercings to allow intestine-like tubes to penetrate their bodies! If they could do that to their own kind, what might they do to prisoners? Better death than such mutilation.

Every night since the flight she had slept badly, even when her new friends had offered her relative safety. She would toss and turn for two hours or so as her mind raced, considering what she could and should have done different, and when she finally slipped into brief, fretful sleep she dreamt only of the battle. She had come to Tilea expecting to face ogres, ostensibly to assist in the reclamation of a realm for a less cruel master and to save what poor souls had been enslaved by the brutes. When that work had been done, however, she had first learned that vampires were also ravaging great swathes of Tilea, and had then, only weeks after ridding Ravola of ogres, been driven from the city by an army of ratmen. This land had been cursed thrice over!

Although it was less than a year ago, it felt like a decade since Perrette had departed Bretonnia. When she set off to cross the high pass into Tilea, she merely wanted to escape Bretonnia, to put her old life behind her and find a new, hopefully better one. Joyously carousing with the Brabanzon one raucous night she found them to be better company than either peasants or noblemen, and not at all as uncouth and callous as one might expect of such a mercenary band. Indeed, she had discovered that the Brabanzon, at least those there that night, possessed an unexpected yet welcome decency, however deeply concealed beneath their swaggering bravado, cruel jests and coarse language. When they told her they were employed to travel to Tilea she had not hesitated in choosing to go with them, despite having no contract herself. Leaving Bretonnia as little better than a camp follower, since the second assault on Campogrotta (and by the Brabanzon’s own choosing) she had come to command the whole company. At least, what was left of it now.

The Brabanzon’s new allies were a mysterious bunch, whose number she had yet to estimate, nor had she ascertained who truly commanded them. The particular band they travelled with had a leader, being the burly Captain Valfrido Gesualdi, but although he had said nothing concerning the matter, something told her that he served another. The name they called themselves – the Arrabbiati, or ‘Angry Ones’ – she had heard during her brief time in Campogrotta when one of the city’s inhabitants had asked her if the reason the Arrabbiati were not amongst the army was because the dwarfs refused to accept their help. During the short conversation that followed she had learned that during the Campogrottans’ time as slaves of Boulderguts’ ogres there had been several incidents of sabotage and assassination against the brutes and it had been generally believed that the Arrabbiati had been behind the deeds. For more than a decade, the brigand band had earned a reputation amongst the common, labouring folk for robbing the most arrogant and tyrannical of the nobility and the greediest of the merchant families – leaving nothing behind but bodies and whichever of their red-fletched arrows had snapped. What with Boulderguts being the very worst of tyrants, his man-eating brutes the most merciless of oppressors, then surely, said her informant, the Arrabbiati would target them? Although at the time she thought it sounded like wishful thinking, it seemed likely that for want of anyone else to rob a band of outlaws might be forced to rob instead from the ogres. Later she learned that they might indeed possess some truly noble motivations, for it was said they been decimated when they had ridden out of nothing but love for the Duchess Maria (regarded as an enlightened and fair ruler, before she became a vampire) to assist in the fight against the vampire Duke Alessandro’s army.

A broad-shouldered man, with a chin as wide as his cheeks, Captain Gesualdi was armed with a bow like the rest of his men but had a scarf about his head instead of a helmet. Like his entire company, he wore dark clothes - his tunic being a dull shade of purple, his scarf burgundy.

Back in Campogrotta Perrette heard one inhabitant refer to the Arrabiatti as the Brotherhood of the Shadows, and it seemed they were indeed suitably dressed to lurk unseen during their nocturnal and crepuscular activities. Some of their horses, however, were white, so either they only hid in shadows when creeping about on foot, or the habit was an affectation to suit their reputation, or, and this surely was most likely, they were loath to waste good horses when they got them.

Their standard was that of a wolfshead, argent upon a sanguine field.

Their modus operandi indicated that this was not a wolf like the white one of Middenland – the forever brawling, bloody, winter wolf of Ulric. Instead, this was a hungry wolf, carefully choosing which prey to stalk and howling at the moon when there were none for miles to hear. The Arrabiatti disparagingly called it the mutt. When the mutt was mounted, they all had to make ready to move. Twice now she had heard them say, ‘Meet at the mutt’, an action made all the easier by the fact that the company’s horn blower always travelled with their standard bearer. Of course, the horn had a sound like a wolf howling.

Now Perette had met them, they seemed so far to warrant their heroic reputation. ‘Goodfellows all,’ they had called themselves at their first encounter, and they did not hesitate to help her and the fleeing Brabanzon. They had offered victuals and shelter, then assisted in the finding of the other Brabanzon survivors. Now they were guiding them by way of these obscure paths away from the city to put them safely on the road back to Campogrotta. In return, they had asked for nothing - at least, not yet. Her own Brabanzon would also have found it in them to help strangers in need, but the matter of remuneration would definitely have been broached long before now! Captain Gesualdi had even gifted her a coat of scale armour which he said would not interfere with her magics for it had once been the property of a wizard. When she asked how it had come into his possession, he answered with a grin that she should not look a gift horse in the mouth.

Three days before, with surely little prospect of profit from a city that had nothing of value left in it when they arrived, and with even less now that the ratmen had infested and consumed it, the captain had dispatched several of his men to scout much closer to the city, out of concern that the ratmen might be preparing to march from the city. She offered some of her own soldiers to accompany the Arrabbiati scouts, for they had recent knowledge of the lay of the land, but Gesualdi had insisted that his men knew the area like the ‘back of their hands’ and that the Brabanzon would do better to scout ahead as they made their way south, searching for any last remaining escapees wandering the wilds.

Perette’s second in command, Osmont, rode much of the way beside her. The riders had previously been commanded by a Sergeant Huget, but he was missing in action, believed to have been shot from his horse by one of the enemy’s long-barrelled muskets before getting out of sight of Ravola’s walls. The man who reported this had died of his wounds only minutes after imparting the news, and so none could now ask him if he was certain! Even if Huget turned up, however, Perrette would keep Osmont as her second, which would put him in command of the riders.

Osmont had an easy relationship with her, often joking - doing so whenever he thought she needed such to lift her spirits but falling quiet when she had a need for sombre contemplation. He had been there in the typpling room of the inn when she first met the company and from the start he seemed to see something in her that she herself had not really been aware of. He was also quite protective. On two occasions, including that first night, he had, with the slightest shake of his head, subtly signalled that the man she was getting close to was not someone she should favour! A veteran of many a war, or at least, many a bloody squabble between this baron and that marquis, he had a calm confidence about him, and a watchfulness. During the fall of Ravola it was he who had understood it was time to leave – not in the sense of being panicked into fleeing, but rather in assessing the situation and recognising that they were beaten.

…

Early in the afternoon a cry was heard from the column of riders behind.

“Ho! Riders! To the left.”

At first, Perrette could see nothing but trees, but then she caught a flashing glimpse of something in motion through the foliage.

“It’s Iginio!” came the same voice again.

“That it is!” came an answering cry. A few moments later the three Arrabiatti scouts emerged from a smaller path which joined the main group’s own route like a tributary stream might merge with a river.

The chief scout, Iginio, wore a dark cloak like many of his comrades and rode a chestnut mount. He came right up to the front of the column to ride beside Perrette and Captain Gesualdi.

“Good captain, my lady, well met!” he said by way of greeting.

“Glad to see you back, Iginio,” said the captain. “Did you get close to the city? The enemy?”

“And the people? What about them?” added Perrette.

“We got close, captain,” said the scout. “Close enough for some of the ratmen to espy us, which is when we left. Apart from a few poor wretches, no more than a dozen, shifting stones under guard where a tower has collapsed, we saw no other people, my lady. There was acrid smoke coming from within, the stink of burning hair and flesh. They must have been burning either beasts or people.”

“Is their entire force still present?” asked the captain.

“Aye, I reckon it is,” said Iginio. Then he addressed Perrette directly. “My lady, you told us they had no war machines?”

“None,” said Perrette. “They took the walls by weight of numbers and had just enough to do so. We battered them badly, killing so many, yet still they came. I pray to all the gods it was their fur you smelled burning.”

“I wish I could affirm that. What I can report is that they do have machines now.”

“They must have lagged behind on their march,” suggested the captain. “Which means they attacked before their full force was mustered, before they had that which could shoot upon the walls.”

“Perhaps arrogance convinced them they would win?” said Perrette. “And that we would not prove a troublesome foe.”

“If so, they learned their lesson, my lady,” said the captain. “From all accounts you put them to far more trouble than an equal number of any other soldiers could have done. The ratmen are bullies, cruel and cunning. They do possess a species of arrogance, for they think they are the only creatures worthy of living in the world. But they are not brave. They rely on strength of numbers in battle, and on terrible machines that can conjure lightning itself. They first bombard their foes, then quickly swarm to overwhelm them before they can recover. There must have been a pressing reason for their haste. It’s likely they were worried you were soon to be reinforced.”

“We did send for help, from Campogrotta. But they attacked long before our messengers could possibly have arrived.”

“My lady, help was sent,” said the scout. “We met with a force from Campogrotta, both heavy and light horsemen, and even some dwarfs following them, catching up every night to sleep for half the time the men did.”

“Compagnia del Sole soldiers?” asked Perrette.

“Aye, my lady, they were. Dispatched from Campogrotta to relieve Ravola but arriving four days too late. They’d scouted the enemy too and were about to return.”

This made little sense to Perrette. Neither the messengers she sent to Campogrotta nor any force of mounted men at arms and dwarfs could possibly have travelled fast enough. The distance was too great. She knew because she had made the journey herself. Even on secret paths such as these for part of the way, it could not be done. Which meant the Compagnia soldiers must have set off long before her messengers arrived. Then it occurred to her – perhaps the soldiers were already on their way for some other reason, and they met her messengers part way?

“Master scout,” she asked. “When you spoke to them, did they say they were ordered from Campogrotta to ride to Ravola’s relief?”

“Yes, my lady. Someone from Ravola came to them and begged that the whole Compagnia go north to your aid. Their captain general sent the riders and dwarfs ahead to learn what they could. They claimed not to know if the commander was following with the rest of the army.”

Perrette held her tongue, but what the man was saying was impossible. Apparently Osmont had not considered the mathematics of the claim, for he asked,

“Master scout, the dwarfs – did you meet with them?”

“Not to speak to. Their commander, I think, was named Greyfury.”

Osmont laughed which made the others look. “He could not bear to be parted from his true love,” he said.

While the others wondered what he could mean, Perette just rolled her eyes and gave Osmont a look meant to silence him. She did not think these men were currently in the mood to entertain private jests. Almost as if she were precognitive, the scout Iginio’s tone changed.

“There was something else we saw. Strange indeed, if truth be told. When we drew close to the city we passed over a long patch of poisoned ground, where all the plants had withered as if baked by a hot sun for many days.”

“We could plainly see no animals had trespassed upon it. There were tracks passing along it, as if left by three large wagons. They had crushed some small trees while brushing past others, so that their blackened remnants still remained erect but sagging. Our mounts became fearful, acting most contrary and we ourselves felt a sudden imbalance in our humours …”

“We did not linger. I don’t think we could have done if we tried. Saladino’s stomach ain’t been right since. We went over it and on, thinking that some poisonous ratman taint must have been released there, a magical curse cast by something on the wagon or some spillage of aqua fortis or the like. Perhaps the ratmen spread corruption from the wagons, as if scattering the very opposite of seeds - sowing death instead of new life? After spying upon the city walls, we chose a different path back, all the better to learn as much as we could of the enemy’s disposition, but mostly to avoid the tainted ground. Yet we again encountered an exactly similar strip of corruption! Loathe to cross it, men and mounts alike, we thought to skirt around it this time. But there was no going around, for the poisoned land proved to be like unto a path, which stretched all the way at least to the first place we had crossed.”

Iginio fell momentarily silent, while the others just waited to hear what else he said.

“I cannot say for certain, but the dead path looked to follow a curved course around the city. We were unable to discover if this was true, for to linger so close to the enemy would surely have meant we were attacked, and to travel any length of time even just beside the corruption may have meant we became too ill to return. But, before we crossed back over, I reckon we got the measure of it. I’d lay all the gold I have that it goes around the entire city.”

“Some sort of magical barrier, perhaps, meant to prevent approach?” suggested Perrette.

“I think not, my lady, for we crossed it twice, there and back again, howsoever loath we were to do so the second time. I doubt anyone could travel along the length of it for more than an hour, yet crossing it takes only a few moments and so is bearable.”

Perrette now noticed the darkness around Iginio’s eyes. She saw too that his horse was sweating noticeably more than her own or the captain’s mount.

“You were exceeding brave to do so,” she said. “And all that you learned of the ratmen, the poor inhabitants and the poisoned band could prove vital to our plans.”

“Iginio,” asked the captain, “how long did you linger in that poisoned place?”

“When we first crossed, just enough time to dismount and look closely at the ground, to notice that the wagons that passed seemed to have differently sized wheels, and some very large, and that they apparently not hauled by draught animals, but of course we could have worked that out without noticing the lack of prints. When we crossed back, we wasted not a moment’s time in getting to the other side.”

“I don’t think it likely they were wagons, but rather some sort of war engines,” said Osmont. “Probably came up with the others you did see. Perhaps they were like giant censers, emitting a cloud of noxious, noisome vapour, which they intend to push at the enemy in battle? As to why they travelled round the city, I know not. Seems a great waste of effort to me just to kill a few trees and weeds.”

“We shall have to take a look at whatever made the dead path,” mused the Arrabiatti captain. “Perhaps then we will learn its true nature and purpose? In the meantime, if your friends the Compagnia soldiers are making their way back to Campogrotta, then we should take you to them.”

“They are not far away, captain,” said the chief scout. “Only two hour’s ride, I reckon.”

“But don’t they have a head start on us?” said Perrette.

“They do, my lady,” agreed the scout. “But they do not know the paths as well as us, and they travel with a long journey in mind, at a pace they can maintain, while we can make a dash to catch up with them.”

…

…

Two hour’s later the riders descended from a high path and rode out towards the even higher hills between them and Campogrotta. Ahead of them, where their present path met with another, they could see a company of horsemen.

Their banner bore the white baton and half-sun emblem of the Compagnia del Sole. They looked surprised at first …

… but Perrette urged her horse out beyond the body, knowing that the soldiers would recall her from Campogrotta. Indeed, the fellow at their fore had drunkenly tried to woo her the night before she left for Ravola!

symphonicpoet

Moderator

The plot thickens now that the targets of the criticality experiment seem to have discovered the existence of the Manratton Project. I fear for Perrette and her band, but she is a wily leader with a strong will to survive and do well by her companions. Eegads!

Padre

Lord

A bucket of flock, a brush and a cloth-mask during the sweeping up process to save my lungs!

After all the practise, one gets adept at these things. One of the scenes above even involved two different kinds of ground - flock and gravel. Never tried that before but I managed it without messing up the sweeping and mixing them up!

After all the practise, one gets adept at these things. One of the scenes above even involved two different kinds of ground - flock and gravel. Never tried that before but I managed it without messing up the sweeping and mixing them up!

symphonicpoet

Moderator

^The flock and gravel for the dead land was a very nice touch. I've contemplated making myself a sand table, which could offer similar benefits. (Particularly since I most often set games on a rather arid world for some reason or other. Kids and their space westerns . . . )

Padre

Lord

Thanks Vonkortez. Here's the prequel to the battle ...

Hoist!

Prequel to the Assault on Ebino, IC2404

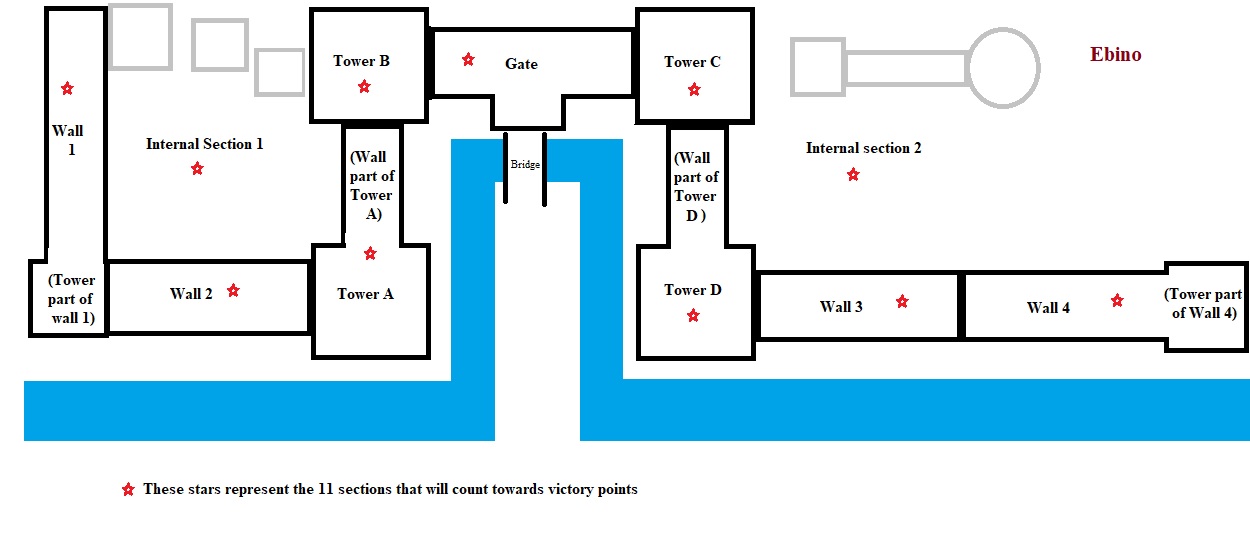

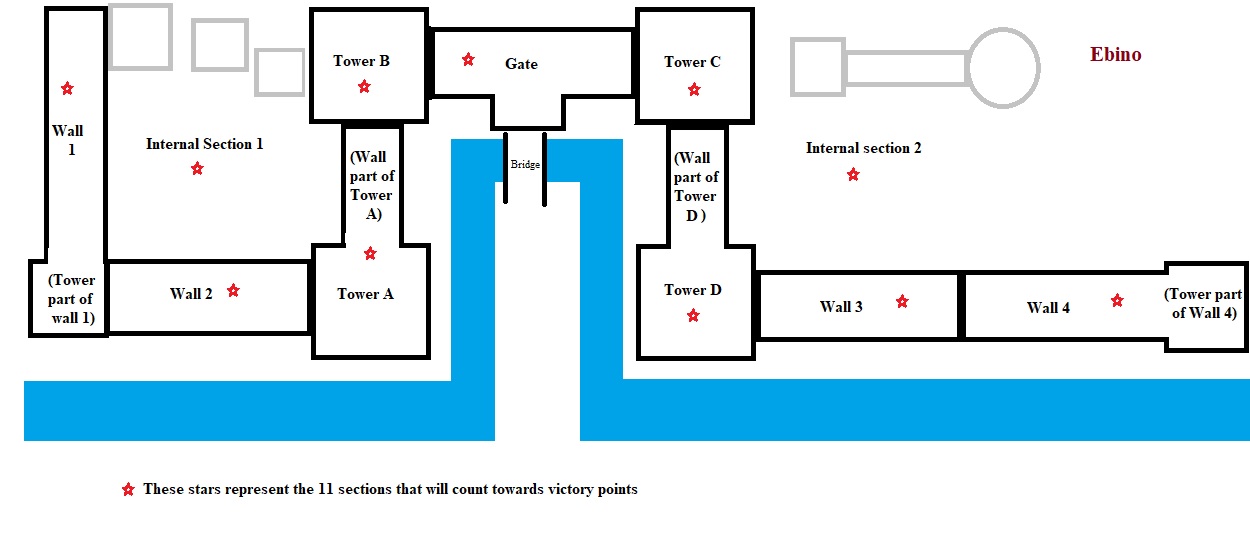

Guccio had been pondering the audacity of his recent behaviour, and whether the consequences of his boldness might prove the ruin of his career prospects in Lord Alessio Falconi’s army, or indeed any army. Faced with the prospect of attacking the strongly walled and deeply moated city of Ebino, defended by an enemy that not only never slept but who had likely forgotten what sleep was, the general had turned to him, as siege master, for advice. He had immediately offered two solutions, both of which now laced his every waking moment with fearful doubt, somehow even surpassing the fear engendered by the prospect of once again facing the undead in battle.

The moat, he had said to Lord Alessio, required bridging, therefore they should fashion carriages to carry suitably long platforms up to the moat’s edge, there to drop into place. Once made busy by the necessarily hasty construction, he had become so caught up in the practicalities of wheels and axles sufficient at least to travel one, relatively short journey, as well as how to counterweight the carriage so that the large platform hanging at the fore would not cause it to topple over, that he had pushed all other concerns from his mind.

Now, however, that the former difficulties had been overcome, howsoever ingeniously, he had to face up to the several many other considerations. Would the sheer weight of both the primary load and necessary counterweight upon such a hastily built carriage simply cause it to shake itself apart as it negotiated the rough ground it would have to pass before reaching the moat? Could any number of men successfully push the thing that far, now that large boulders had been strapped to the rear to compensate for the force of the large, leaning bridge platform hanging precariously from the front? And when the timber platform was allowed to fall, would it stay in one piece as it crashed into the ground, as well as sufficiently strong to bear the weight of the many armoured men (carrying long ladders) who would then pour over the top of it in order to reach the foot of the wall?

While these were just some of his worries concerning the bridges, all paled into insignificance when compared to his worries regarding the petard.

The scouts had reported that the city’s southern gate had a stone bridge leading to it, which obviously could not be drawn up – a rather unexpected opportunity for access given the fact that the city’s builders had gone to the trouble of digging a moat. Knowing therefore that the gate could be reached relatively easily, Guccio immediately wondered how the gate itself might be broken through. Of course, there were artillery pieces that could do the job, and master gunners to tend them, but only two, and not the half a dozen they had fielded in the Valley of Death. If one or even both should shiver as had the mortar at Pontremola, then the gate might not be beaten. Furthermore, the scouts had reported that it was made of iron-bound oak, ancient and hard, reinforced by a huge iron portcullis, which of course made sense considering the lack of a drawbridge. It was clear that the army needed another string to its bow when it came to the gate. To Guccio’s mind there was no choice - breaking gate had to be attempted, if simply as an alternative mode of access should his doubts concerning his bridges prove warranted.

Thus it was, as if he were a boulder rolling downhill, entirely unable to stop, he found himself making a second proposal to the general, immediately following his first: they would need a petard, one of substantial size and great potency, and he knew where to obtain just such a thing. The mortar that had shivered at Pontremola had not blown itself entirely apart, but rather had merely cracked, rendering itself entirely unsafe for the purpose it was made to perform. Guccio said that if it were loaded with grenade and triple the weight of powder and mounted upon a carriage, then it could be rolled right up to the gate, placed against it, and exploded. It would surely blow itself apart, considering its visibly fractured state, but in so doing most likely tear the gate to pieces, dislodge the portcullis and provide a breach through which the army could pour.

That moment, as all those gathered in the army council nodded appreciatively, including the general himself, should have been a moment of great satisfaction – if he had not immediately realised how little certainty he had that any of what he had claimed was even vaguely likely to succeed.

Thus the knot in his stomach ever since!

…

Its carriage completed - utilising the wheels of one of the army’s better baggage wagons, much to the disgust of the proud carter who had coaxed the carriage all the way from Portomaggiore - the petard was now being rolled out of the camp, just as the rest of the army was readying itself for the challenge ahead.

Guccio watched, standing beside the sergeant of the handgunners who had been volunteered as petardiers, a fellow named Vasari. Until now the sergeant had said very little, although from his gruff attitude it was clear he was not thrilled at what he and his men had been ordered to do. A bearded veteran of several wars, which included serving with Lord Alessio in the northern Old World, he was tall and every bit the image of a soldier, albeit one dressed (as so many in the Portomaggioran marching army) in Empire style clothes.

“I was told it would be a simple task,” the sergeant suddenly declared. “Yet here we see how hard it is even just to move it. Tell me, siege master, why don’t we haul it with draft animals like the bridges?”

“We could, I suppose, at least until we drew close to the walls,” said Guccio. “If we were not using nearly every horse to haul the bridges instead. Besides, your men will learn how to push it along the way.”

“Ah, the fine and noble art of pushing,” said the sergeant, rolling his eyes.

This made Guccio smile. “Aye, well, not noble, but your men must familiarise themselves with the work, all the better to move speedily and without hindrance when they draw near.”

“Yet such an enemy will not shoot at us. Not once have I seen them so much as lob a stone, never mind span and shoot a crossbow nor load and fire a piece,” said the sergeant. “We could haul it up all leisurely, take a breather now and then, have a little repast as and when we like, and still it would be delivered.”

“The enemy might not shoot, but who knows what might sally forth from the city if we approach so slowly as to allow them to get the measure of us? Who knows what magical incantations their foul masters might conjure against us? And we needs must time our arrival as best we can with the arrival of the bridges and the ladder assault on the walls, so that the enemy cannot concentrate its strength against us.”

“I doubt the bridges will be moving fast at all”

“That’s as may be,” agreed Guccio. “But if we are to coordinate the arrival perfectly, we must light the fuse as we draw near, after which your men cannot afford to slip or stall, otherwise the fuse will have to be pulled out and replaced and re-lit, allowing the enemy even more time to thwart us.”

“My men,” mused the sergeant. “You mean my men and I.”

Guccio fell silent, for what could he say? Every veteran knew the dangerous reputation of petards.

“When the arch-lector was considering attacking Ebino,” said the sergeant, “they say the maestro Angelo da Leoni built him a huge ramp, hauled by his steam engine, up which the army could stroll right up and over the walls into the city.”

Except the maestro failed, thought Guccio. “Would that we could, sergeant” was what he said. “But we have no such engine.”

The construction of a ramp for Da Leoni’s steam engine had taken so long that the vampire Duchess had sallied forth from the city and defeated the living army in the field. The maestro’s engine, stripped bare of its armaments, had sputtered forwards and ground to a halt when swarmed by ghostly monsters. The thought made Guccio’s stomach knot the more. If a genius like Da Leoni had failed, with his unique marvel of an engine, how could his own ‘grenado in a hand cart’ hope to work? Or his clackety timber bridges?

Just now four men were pushing the petard, as indeed his design intended. But when it approached the city, Sergeant Vasari’s whole company would accompany it, to guard it should that prove necessary, and more importantly to assist if it were to get stuck, or one or more of the pushers should fall from whatever harm the enemy inflicted.

“You’ve tested the fuse, I take it?” asked Sergeant Vasari.

The fuse hung from the touchhole at the rear, a particularly potent, hempen matchcord boiled in a concentrated saltpetre solution, that would spit spluttering sparks when lit, the flame burning up at a speed much faster than that of any handgunner’s ‘slowmatch’.

“That I have. I made four, all exactly the same. Two I tested and timed, the third you see there, the fourth I will have with me should we need to replace that one.”

“You will be with us?” said the sergeant, with evident surprise.

It had not occurred to Guccio that the sergeant did not know he was to stay with the petard. “I will, although I might be of little use should it come to fighting, for my skills with a blade are somewhat rusty.”

“Well, siege-master,” said the sergeant, his tone lightening. “We’ll do any fighting that’s needed, you just make sure that thing goes off when it is supposed to go off, and not a moment before.”

That’s the trick, thought Guccio. And that is what every soldier in Vasari’s company had on his mind. Now that the sergeant knew the petard’s maker was to be with them, he seemed less anxious. Knowing the man responsible for building it was to risk his own life also had to make anyone feel a bit better about the prospect of success, for why would a man make a petard with which to hoist his very own self?

Except Guccio was the maker and knew full well what a man might do when he allows ambition and pride to take the reins of his own voice. It was a good thing that the sergeant could not feel how dry Guccio’s throat was or sense the ever-present knot inside his belly.

Behind them several companies of soldiers had already mustered and begun their march. An Estalian mercenary commanded one band of handgunners …

… while a swaggering youth with an oversized panache strode with bared blade ahead of another company.

Elsewhere in this part of the camp, soldiers rushed to arm themselves and collect whatever they might need for the short march and the battle ahead. A number were drawing fortified wine from a cart, for it was the custom for every soldier to drink a deep draft before an assault, not just to calm their nerves but to embolden them. It was a practice made all the more appropriate when the enemy consisted of those who had already died!

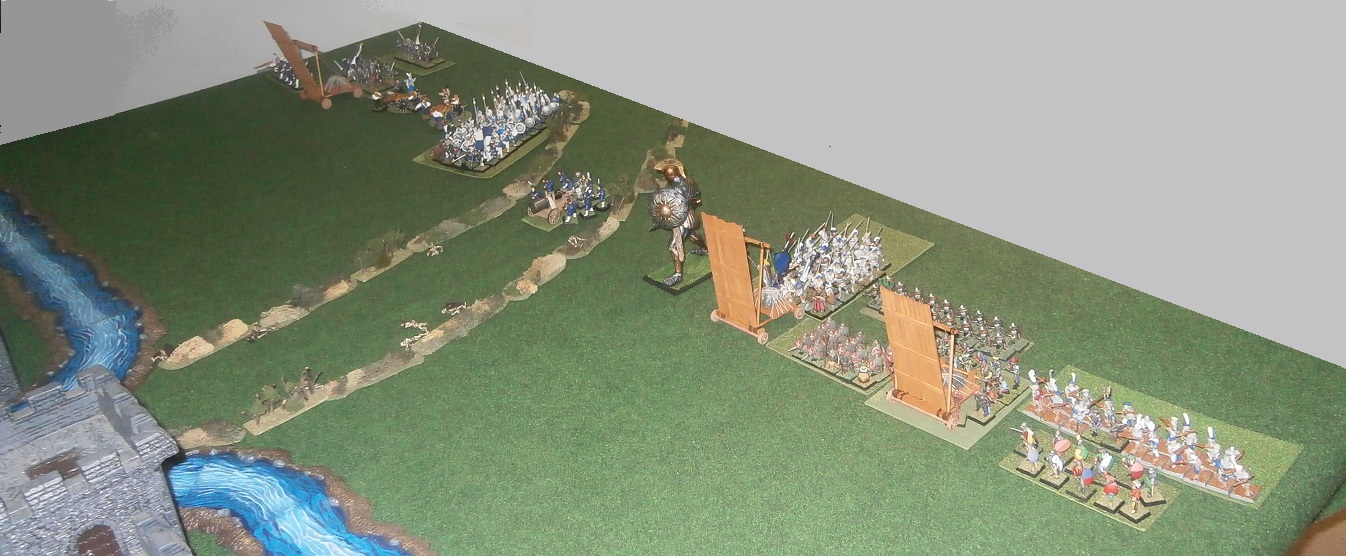

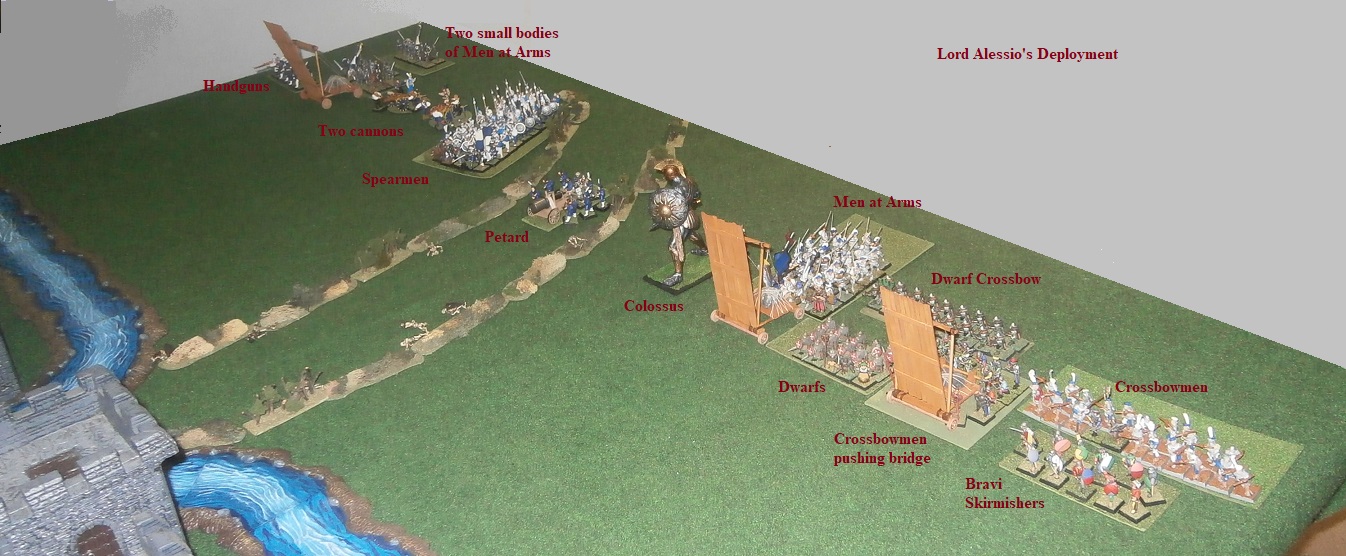

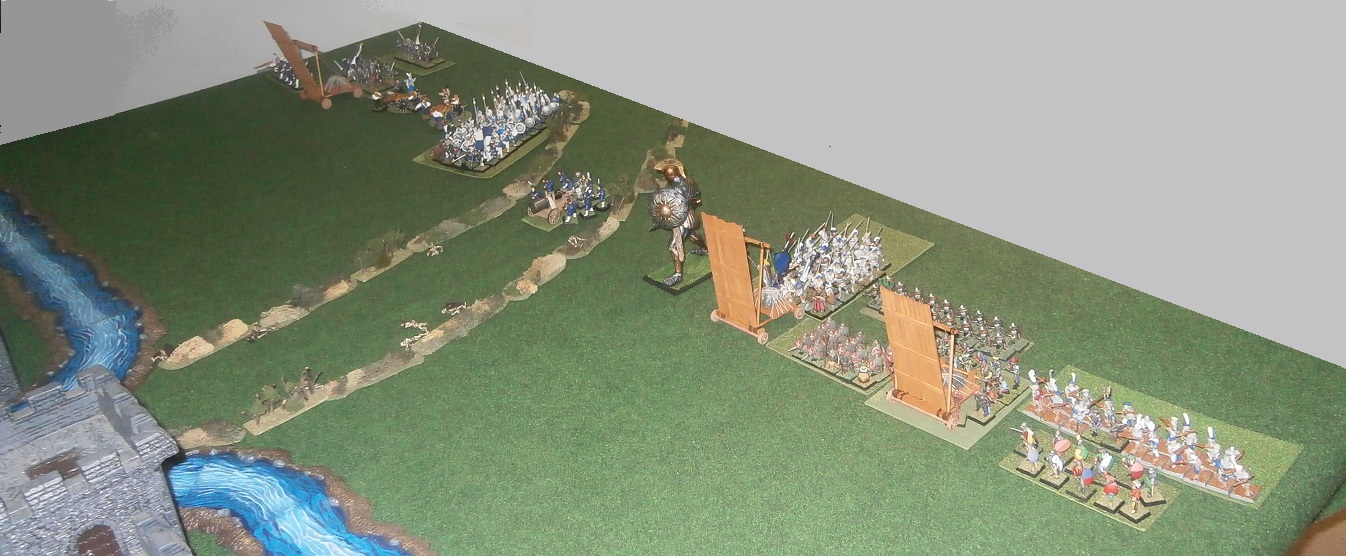

Behind the petard trundled Guccio’s three large bridges, made slow by the huge, counterweight rocks he had ordered lashed to the platforms.

These were to be pulled by beasts to within sight of the walls, and then distributed to three of the larger regiments to be pushed the remainder of the way. To ask soldiers to push them was impractical but entirely necessary, for if the draught animals were to be alarmed by the enemy, startled in such a way as to buck or rear, then the bridges could topple before they reached the moat.

Still, thought Guccio, I will be so busy with the petard I might not even notice such a disaster!

May blessed Myrmidia, he prayed, protect me in the battle to come. And should I die in the blast, then may the goddess take my life as a sacrificial offering in return for breaking the gate, so that my life may not be wasted and that our army, dedicated to her, may gain victory against this the foulest of foes.

Hoist!

Prequel to the Assault on Ebino, IC2404

Guccio had been pondering the audacity of his recent behaviour, and whether the consequences of his boldness might prove the ruin of his career prospects in Lord Alessio Falconi’s army, or indeed any army. Faced with the prospect of attacking the strongly walled and deeply moated city of Ebino, defended by an enemy that not only never slept but who had likely forgotten what sleep was, the general had turned to him, as siege master, for advice. He had immediately offered two solutions, both of which now laced his every waking moment with fearful doubt, somehow even surpassing the fear engendered by the prospect of once again facing the undead in battle.

The moat, he had said to Lord Alessio, required bridging, therefore they should fashion carriages to carry suitably long platforms up to the moat’s edge, there to drop into place. Once made busy by the necessarily hasty construction, he had become so caught up in the practicalities of wheels and axles sufficient at least to travel one, relatively short journey, as well as how to counterweight the carriage so that the large platform hanging at the fore would not cause it to topple over, that he had pushed all other concerns from his mind.

Now, however, that the former difficulties had been overcome, howsoever ingeniously, he had to face up to the several many other considerations. Would the sheer weight of both the primary load and necessary counterweight upon such a hastily built carriage simply cause it to shake itself apart as it negotiated the rough ground it would have to pass before reaching the moat? Could any number of men successfully push the thing that far, now that large boulders had been strapped to the rear to compensate for the force of the large, leaning bridge platform hanging precariously from the front? And when the timber platform was allowed to fall, would it stay in one piece as it crashed into the ground, as well as sufficiently strong to bear the weight of the many armoured men (carrying long ladders) who would then pour over the top of it in order to reach the foot of the wall?

While these were just some of his worries concerning the bridges, all paled into insignificance when compared to his worries regarding the petard.

The scouts had reported that the city’s southern gate had a stone bridge leading to it, which obviously could not be drawn up – a rather unexpected opportunity for access given the fact that the city’s builders had gone to the trouble of digging a moat. Knowing therefore that the gate could be reached relatively easily, Guccio immediately wondered how the gate itself might be broken through. Of course, there were artillery pieces that could do the job, and master gunners to tend them, but only two, and not the half a dozen they had fielded in the Valley of Death. If one or even both should shiver as had the mortar at Pontremola, then the gate might not be beaten. Furthermore, the scouts had reported that it was made of iron-bound oak, ancient and hard, reinforced by a huge iron portcullis, which of course made sense considering the lack of a drawbridge. It was clear that the army needed another string to its bow when it came to the gate. To Guccio’s mind there was no choice - breaking gate had to be attempted, if simply as an alternative mode of access should his doubts concerning his bridges prove warranted.

Thus it was, as if he were a boulder rolling downhill, entirely unable to stop, he found himself making a second proposal to the general, immediately following his first: they would need a petard, one of substantial size and great potency, and he knew where to obtain just such a thing. The mortar that had shivered at Pontremola had not blown itself entirely apart, but rather had merely cracked, rendering itself entirely unsafe for the purpose it was made to perform. Guccio said that if it were loaded with grenade and triple the weight of powder and mounted upon a carriage, then it could be rolled right up to the gate, placed against it, and exploded. It would surely blow itself apart, considering its visibly fractured state, but in so doing most likely tear the gate to pieces, dislodge the portcullis and provide a breach through which the army could pour.

That moment, as all those gathered in the army council nodded appreciatively, including the general himself, should have been a moment of great satisfaction – if he had not immediately realised how little certainty he had that any of what he had claimed was even vaguely likely to succeed.

Thus the knot in his stomach ever since!

…

Its carriage completed - utilising the wheels of one of the army’s better baggage wagons, much to the disgust of the proud carter who had coaxed the carriage all the way from Portomaggiore - the petard was now being rolled out of the camp, just as the rest of the army was readying itself for the challenge ahead.

Guccio watched, standing beside the sergeant of the handgunners who had been volunteered as petardiers, a fellow named Vasari. Until now the sergeant had said very little, although from his gruff attitude it was clear he was not thrilled at what he and his men had been ordered to do. A bearded veteran of several wars, which included serving with Lord Alessio in the northern Old World, he was tall and every bit the image of a soldier, albeit one dressed (as so many in the Portomaggioran marching army) in Empire style clothes.

“I was told it would be a simple task,” the sergeant suddenly declared. “Yet here we see how hard it is even just to move it. Tell me, siege master, why don’t we haul it with draft animals like the bridges?”

“We could, I suppose, at least until we drew close to the walls,” said Guccio. “If we were not using nearly every horse to haul the bridges instead. Besides, your men will learn how to push it along the way.”

“Ah, the fine and noble art of pushing,” said the sergeant, rolling his eyes.

This made Guccio smile. “Aye, well, not noble, but your men must familiarise themselves with the work, all the better to move speedily and without hindrance when they draw near.”

“Yet such an enemy will not shoot at us. Not once have I seen them so much as lob a stone, never mind span and shoot a crossbow nor load and fire a piece,” said the sergeant. “We could haul it up all leisurely, take a breather now and then, have a little repast as and when we like, and still it would be delivered.”

“The enemy might not shoot, but who knows what might sally forth from the city if we approach so slowly as to allow them to get the measure of us? Who knows what magical incantations their foul masters might conjure against us? And we needs must time our arrival as best we can with the arrival of the bridges and the ladder assault on the walls, so that the enemy cannot concentrate its strength against us.”

“I doubt the bridges will be moving fast at all”

“That’s as may be,” agreed Guccio. “But if we are to coordinate the arrival perfectly, we must light the fuse as we draw near, after which your men cannot afford to slip or stall, otherwise the fuse will have to be pulled out and replaced and re-lit, allowing the enemy even more time to thwart us.”

“My men,” mused the sergeant. “You mean my men and I.”

Guccio fell silent, for what could he say? Every veteran knew the dangerous reputation of petards.

“When the arch-lector was considering attacking Ebino,” said the sergeant, “they say the maestro Angelo da Leoni built him a huge ramp, hauled by his steam engine, up which the army could stroll right up and over the walls into the city.”

Except the maestro failed, thought Guccio. “Would that we could, sergeant” was what he said. “But we have no such engine.”

The construction of a ramp for Da Leoni’s steam engine had taken so long that the vampire Duchess had sallied forth from the city and defeated the living army in the field. The maestro’s engine, stripped bare of its armaments, had sputtered forwards and ground to a halt when swarmed by ghostly monsters. The thought made Guccio’s stomach knot the more. If a genius like Da Leoni had failed, with his unique marvel of an engine, how could his own ‘grenado in a hand cart’ hope to work? Or his clackety timber bridges?

Just now four men were pushing the petard, as indeed his design intended. But when it approached the city, Sergeant Vasari’s whole company would accompany it, to guard it should that prove necessary, and more importantly to assist if it were to get stuck, or one or more of the pushers should fall from whatever harm the enemy inflicted.

“You’ve tested the fuse, I take it?” asked Sergeant Vasari.

The fuse hung from the touchhole at the rear, a particularly potent, hempen matchcord boiled in a concentrated saltpetre solution, that would spit spluttering sparks when lit, the flame burning up at a speed much faster than that of any handgunner’s ‘slowmatch’.

“That I have. I made four, all exactly the same. Two I tested and timed, the third you see there, the fourth I will have with me should we need to replace that one.”

“You will be with us?” said the sergeant, with evident surprise.

It had not occurred to Guccio that the sergeant did not know he was to stay with the petard. “I will, although I might be of little use should it come to fighting, for my skills with a blade are somewhat rusty.”

“Well, siege-master,” said the sergeant, his tone lightening. “We’ll do any fighting that’s needed, you just make sure that thing goes off when it is supposed to go off, and not a moment before.”

That’s the trick, thought Guccio. And that is what every soldier in Vasari’s company had on his mind. Now that the sergeant knew the petard’s maker was to be with them, he seemed less anxious. Knowing the man responsible for building it was to risk his own life also had to make anyone feel a bit better about the prospect of success, for why would a man make a petard with which to hoist his very own self?

Except Guccio was the maker and knew full well what a man might do when he allows ambition and pride to take the reins of his own voice. It was a good thing that the sergeant could not feel how dry Guccio’s throat was or sense the ever-present knot inside his belly.

Behind them several companies of soldiers had already mustered and begun their march. An Estalian mercenary commanded one band of handgunners …

… while a swaggering youth with an oversized panache strode with bared blade ahead of another company.

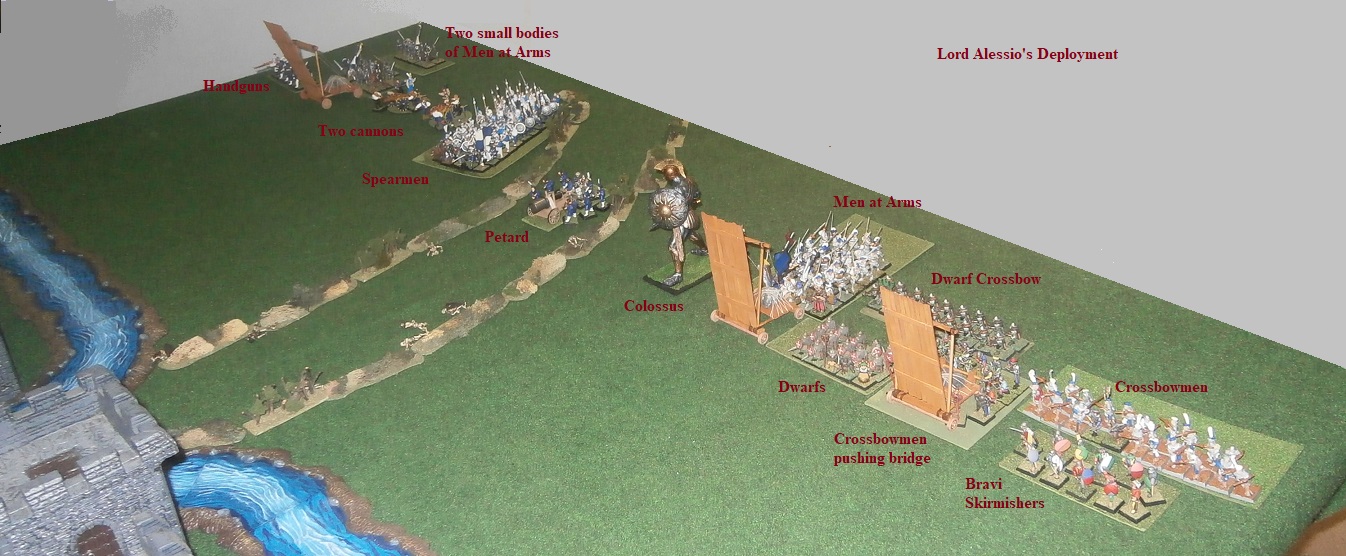

Elsewhere in this part of the camp, soldiers rushed to arm themselves and collect whatever they might need for the short march and the battle ahead. A number were drawing fortified wine from a cart, for it was the custom for every soldier to drink a deep draft before an assault, not just to calm their nerves but to embolden them. It was a practice made all the more appropriate when the enemy consisted of those who had already died!