You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Tilea IC2401 (Campaign#8)

- Thread starter Padre

- Start date

The Fat Git

Vassal

That's terrible! Have you considered changing to Flickr? A Tb of photos. That doesn't make losing all the old pictures any easier to bear though. You could always take the plunge into blogging instead. Just add you blog to the news feed on here. Both my suggestions involve a lot of work on your part, just uploading the pictures (hoping you still have hard copies).

Padre

Lord

I have now established that this involved 3600 individual photographs scattered over several forums in battle reports, stories and articles with anything from a few to 50+ photos each, going back 11 years.

I have managed to extract 3500 of the photos from Photobucket so that at least I have my own copies in an easily identifiable place (the originals are scattered over umnpteen folders and files on several different machines and memory devices!).

I think, Sean and Fat Git, I agree with you. Best way is to start a website and slowly but surely upload to create an uber WFB-story/batrep site. It will take no less time than Flickr or the other hosting sites. I know all the forum threads will be left torn to pieces, but if I went the hosting route again who's to say whether I would do all the work only to have it happen again.

Bloody photobucket. If they'd asked for $100 a year I'd have paid. But $400, out of the blue, without warning, and for a service that up 'til now has been time consuming agony to use, and which I now utterly distrust, is madness.

My only fear is whether I can construt a website with Wordpress that shows the campaigns the right way around. Most blogs (all?) have the latest post, then reverse chronology. That really doesn't work for a story-campaign.

It occurs to me now. You bloggers, is there a Wordpress template that works like a collection of stories with chapters, rather than a reverse chronological diary?

I have managed to extract 3500 of the photos from Photobucket so that at least I have my own copies in an easily identifiable place (the originals are scattered over umnpteen folders and files on several different machines and memory devices!).

I think, Sean and Fat Git, I agree with you. Best way is to start a website and slowly but surely upload to create an uber WFB-story/batrep site. It will take no less time than Flickr or the other hosting sites. I know all the forum threads will be left torn to pieces, but if I went the hosting route again who's to say whether I would do all the work only to have it happen again.

Bloody photobucket. If they'd asked for $100 a year I'd have paid. But $400, out of the blue, without warning, and for a service that up 'til now has been time consuming agony to use, and which I now utterly distrust, is madness.

My only fear is whether I can construt a website with Wordpress that shows the campaigns the right way around. Most blogs (all?) have the latest post, then reverse chronology. That really doesn't work for a story-campaign.

It occurs to me now. You bloggers, is there a Wordpress template that works like a collection of stories with chapters, rather than a reverse chronological diary?

Subedai

Baron

Luckily I had caught up with the campaign recently. Great battle that was exciting to read about, I hope to see more of the rampaging ogre tribe soon (though I am rooting for the city states, not least because of their dwarf mercenaries).

Glad to hear you are not too dispirited by the PB fiasco and are joining Wordpress. Looking forward to the new format - if there is anything I can help with, give me a shout, as I'm on WP myself.

Glad to hear you are not too dispirited by the PB fiasco and are joining Wordpress. Looking forward to the new format - if there is anything I can help with, give me a shout, as I'm on WP myself.

Padre

Lord

All hail the Oldhammer Admin. The entire thread is restored. The evil Ph'Buck empire is defeated and the world put to rights.

I am, quite literally, ecstatic.

Consequently, I will stop working on the web-site version of the campaign and continue the work I was doing on the next campaign story when the photobucket disaster hit.

The next story, although I say it myself, should be a good one. Well, pretty pictures at the least!

I am dizzy with excitement.

I am, quite literally, ecstatic.

Consequently, I will stop working on the web-site version of the campaign and continue the work I was doing on the next campaign story when the photobucket disaster hit.

The next story, although I say it myself, should be a good one. Well, pretty pictures at the least!

I am dizzy with excitement.

Padre

Lord

The Church of Nagash

Near Viadaza, northern Tilea, Spring 2403

The graveyards were empty, the tombs bereft of bones. Viadaza had been harvested of all that could be made undead many months before, upon Lord Adolfo’s command. Yet once again the city swarmed with the vampires’ servants, an army of animated warriors with or without rotting flesh, having this time marched upon the city rather than arisen within it. There had been no shortage of corpses after the battle at Ebino to swell the shambling horde, which meant Biagino, craving followers for his new Church of Nagash, had been generously provided for. He arrived at the city with quite a congregation – not only the select servants of La Fraternita di Morti Irrequieti, but also the wild mob of his Disciplinati di Nagash. He had also been gifted the famous Cattedrale di Morr Re, which sat in its extensive grounds a little way north-east of the city walls. All this he received with a degree of satisfaction, but he knew it was not enough. If his church was to thrive, if Nagash was to be fed by its prayers and so return his blessings, then there was one more, (quite literally) vital thing he needed. Hopefully, Viadaza would provide.

As he waited before the castle-like front of the Cattedrale, he was accompanied by a cluster of servants.

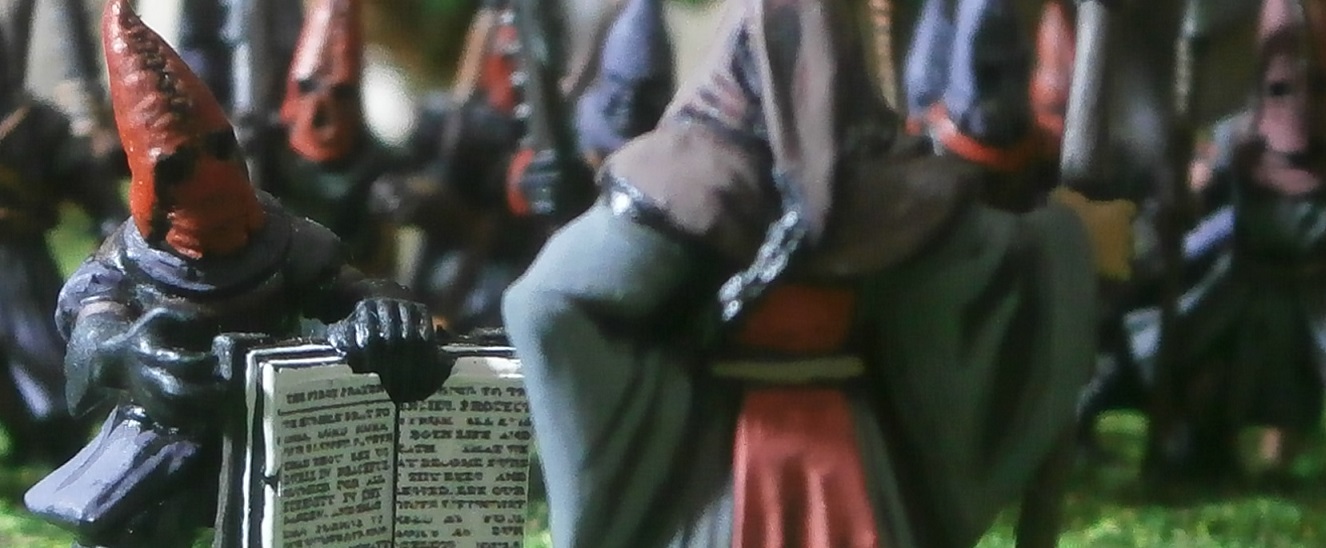

Several zombies staggered hither and thither about their labours, lifting or dragging the last pieces of debris away so that the grassy space was almost pristine. Biagino’s guards and attendants, however, were silent and, for the most part, motionless. Three red-robed brothers stood in prayerful contemplation. They possessed a serenity which sometimes concealed their deep wickedness and at other times gave it a sharper edge. For now, they merely waited.

The first of Biagino’s Disciplinati was also present, his head a battered mess of misshapen bone and torn flesh, his hands disfigured by their size, somehow both swollen and emaciated at one and the same time, the splayed fingers elongated beyond their natural length. He still wore the dedicant’s robes he had been captured in, bar the gloves, of course.

Biagino had intended to turn this man into one of his Fraternita thralls, as he had done with several of those who had been captured alive, but in a fitful moment of uncontrolled bloodlust during the enspelling he had gone a tad too far and accidentally killed the man. Not wanting to waste the corpse, he chose instead to re-animate it. When he saw what resulted he decided there and then to form his Disciplinati di Morr, a huge mob of crazed un-corpses who would serve, as they had in life, as bloodthirsty dedicants, footsoldiers for his church, while his Fraternita would be his priests, clerks and lieutenants.

Apart from the rustling of leaves in the breeze and the faint sound of grunting and groaning from the foul mob contained within the cattedrali’s cloistered quadrangle, all was quiet on the tree-lined green.

Biagino had been waiting for another of his servants, a captain of his skeletal body-guard, to arrive. While he did so, he gave his mind up to the powerful swirl of gleeful desires born of his vampiric lusts, suffusing him thoroughly, and conjoining with the winds of magic animating his frame. He felt a surge building and allowed it to pour outwards, feeding all those around him and amplifying the eerie sound issuing from within the walls behind him.

Then something bright caught his eye and he realised the captain was already present - sunlight reflecting from the curved blade of the captain’s ancient war scythe.

“What news, captain?” Biagino demanded. “How many? And are they coming?”

The captain responded immediately, yet neither by movement nor sound. His answer was without words, for he knew not the modern tongue and had no tongue to speak it. It was contained in a thought, or rather the echo of a thought, which washed through Biagino’s mind with cruel clarity.

They are coming, but it will be some time yet. There are not many, less than a hundred.

“So few?”

The city is almost empty. All the rest have fled.

“Which means I get the slow, the foolish and the unlucky?”

They live.

“Yes,” said Biagino. “At least they are alive. And they must stay that way until they have yielded unto Nagash all that they can – every anguished prayer and fearful misery. I will turn their screams into hymns, their cries into plainsong. Their torment will be delicious as their suffering sates our lord’s hunger.”

He thought of the blood he would take from them in their last moments. It would be a meagre nourishment, like thin gruel, but in great quantity. This in turn stirred in him the ancient hunger, a distraction he refused to yield to.

“It seems we have time on our hands,” he said. “We shall put it to good use and further prepare this temple for its unholy purpose. I will have it made ready before the worshippers arrive.”

Biagino turned to the first of his Disciplinati.

“It is time for your brothers to begin the vapouring,” he declared. Then he looked upon the three Fraternita.

“Bring the tome,” he ordered. One of the red-robed thralls stepped forwards to proffer said book.

Biagino made a sign over the book and gave a short prayer in the classical Reman tongue: “In virtute Nagash, non somnus, non requiem.”

The thrall then opened the book to a page marked by a finger bone and turned it around to allow Biagino to read its ancient text. He did so, aloud, intoning the words with exaggerated expression, an almost mocking tone. Allowing the etheric breeze to penetrate him deeply, to coalesce and swirl through and about his mind, he summoned his Disciplinati.

For a few moments only his shrill voice could be heard, but then another sound joined it, not one but many voices. They were wordless, first groans and moans, then guttural cries and growls. Biagino turned to look at the trees to his left. The others did the same …

… and he cried out, “There! My bambini. See how they run!”

They poured from the catedrale, their pace frantic, their arms outstretched, still part-clothed in the ragged remains of their Morrite robes.

“Ha!” laughed Biagino. “Look at them! They have not forgotten, but now they dance for Nagash!”

The Disciplinati cavorted onwards, forming a long column. Some carried the weapons they had died with …

… while others ran empty handed.

Wild they ran, barely balanced, as if falling ever forwards, each step made just in time to prevent a tumble.

Some wore the red or grey hoods of Morrite flagellants, others were topped with matted, ragged hair, while many were bald and bloody.

As they emerged from behind the trees onto the open space, their course began to alter.

The crazed column began to curve across the front of the catedrale, to commence its circumnavigation of the grounds.

Just as they had done at Ebino, when they hurtled pell-mell around the holy carroccio, they now did the same here, so that their clamourous cavorting might sanctify the catedrale. This time, however, they served a different god.

The Church of Nagash was truly re-born!

Near Viadaza, northern Tilea, Spring 2403

The graveyards were empty, the tombs bereft of bones. Viadaza had been harvested of all that could be made undead many months before, upon Lord Adolfo’s command. Yet once again the city swarmed with the vampires’ servants, an army of animated warriors with or without rotting flesh, having this time marched upon the city rather than arisen within it. There had been no shortage of corpses after the battle at Ebino to swell the shambling horde, which meant Biagino, craving followers for his new Church of Nagash, had been generously provided for. He arrived at the city with quite a congregation – not only the select servants of La Fraternita di Morti Irrequieti, but also the wild mob of his Disciplinati di Nagash. He had also been gifted the famous Cattedrale di Morr Re, which sat in its extensive grounds a little way north-east of the city walls. All this he received with a degree of satisfaction, but he knew it was not enough. If his church was to thrive, if Nagash was to be fed by its prayers and so return his blessings, then there was one more, (quite literally) vital thing he needed. Hopefully, Viadaza would provide.

As he waited before the castle-like front of the Cattedrale, he was accompanied by a cluster of servants.

Several zombies staggered hither and thither about their labours, lifting or dragging the last pieces of debris away so that the grassy space was almost pristine. Biagino’s guards and attendants, however, were silent and, for the most part, motionless. Three red-robed brothers stood in prayerful contemplation. They possessed a serenity which sometimes concealed their deep wickedness and at other times gave it a sharper edge. For now, they merely waited.

The first of Biagino’s Disciplinati was also present, his head a battered mess of misshapen bone and torn flesh, his hands disfigured by their size, somehow both swollen and emaciated at one and the same time, the splayed fingers elongated beyond their natural length. He still wore the dedicant’s robes he had been captured in, bar the gloves, of course.

Biagino had intended to turn this man into one of his Fraternita thralls, as he had done with several of those who had been captured alive, but in a fitful moment of uncontrolled bloodlust during the enspelling he had gone a tad too far and accidentally killed the man. Not wanting to waste the corpse, he chose instead to re-animate it. When he saw what resulted he decided there and then to form his Disciplinati di Morr, a huge mob of crazed un-corpses who would serve, as they had in life, as bloodthirsty dedicants, footsoldiers for his church, while his Fraternita would be his priests, clerks and lieutenants.

Apart from the rustling of leaves in the breeze and the faint sound of grunting and groaning from the foul mob contained within the cattedrali’s cloistered quadrangle, all was quiet on the tree-lined green.

Biagino had been waiting for another of his servants, a captain of his skeletal body-guard, to arrive. While he did so, he gave his mind up to the powerful swirl of gleeful desires born of his vampiric lusts, suffusing him thoroughly, and conjoining with the winds of magic animating his frame. He felt a surge building and allowed it to pour outwards, feeding all those around him and amplifying the eerie sound issuing from within the walls behind him.

Then something bright caught his eye and he realised the captain was already present - sunlight reflecting from the curved blade of the captain’s ancient war scythe.

“What news, captain?” Biagino demanded. “How many? And are they coming?”

The captain responded immediately, yet neither by movement nor sound. His answer was without words, for he knew not the modern tongue and had no tongue to speak it. It was contained in a thought, or rather the echo of a thought, which washed through Biagino’s mind with cruel clarity.

They are coming, but it will be some time yet. There are not many, less than a hundred.

“So few?”

The city is almost empty. All the rest have fled.

“Which means I get the slow, the foolish and the unlucky?”

They live.

“Yes,” said Biagino. “At least they are alive. And they must stay that way until they have yielded unto Nagash all that they can – every anguished prayer and fearful misery. I will turn their screams into hymns, their cries into plainsong. Their torment will be delicious as their suffering sates our lord’s hunger.”

He thought of the blood he would take from them in their last moments. It would be a meagre nourishment, like thin gruel, but in great quantity. This in turn stirred in him the ancient hunger, a distraction he refused to yield to.

“It seems we have time on our hands,” he said. “We shall put it to good use and further prepare this temple for its unholy purpose. I will have it made ready before the worshippers arrive.”

Biagino turned to the first of his Disciplinati.

“It is time for your brothers to begin the vapouring,” he declared. Then he looked upon the three Fraternita.

“Bring the tome,” he ordered. One of the red-robed thralls stepped forwards to proffer said book.

Biagino made a sign over the book and gave a short prayer in the classical Reman tongue: “In virtute Nagash, non somnus, non requiem.”

The thrall then opened the book to a page marked by a finger bone and turned it around to allow Biagino to read its ancient text. He did so, aloud, intoning the words with exaggerated expression, an almost mocking tone. Allowing the etheric breeze to penetrate him deeply, to coalesce and swirl through and about his mind, he summoned his Disciplinati.

For a few moments only his shrill voice could be heard, but then another sound joined it, not one but many voices. They were wordless, first groans and moans, then guttural cries and growls. Biagino turned to look at the trees to his left. The others did the same …

… and he cried out, “There! My bambini. See how they run!”

They poured from the catedrale, their pace frantic, their arms outstretched, still part-clothed in the ragged remains of their Morrite robes.

“Ha!” laughed Biagino. “Look at them! They have not forgotten, but now they dance for Nagash!”

The Disciplinati cavorted onwards, forming a long column. Some carried the weapons they had died with …

… while others ran empty handed.

Wild they ran, barely balanced, as if falling ever forwards, each step made just in time to prevent a tumble.

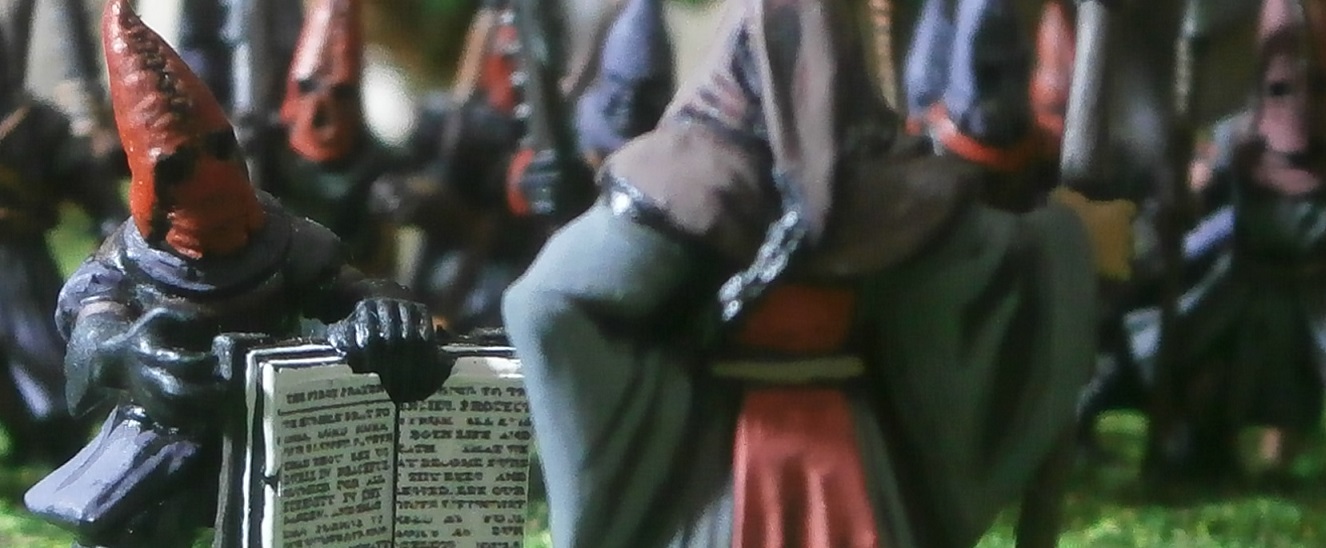

Some wore the red or grey hoods of Morrite flagellants, others were topped with matted, ragged hair, while many were bald and bloody.

As they emerged from behind the trees onto the open space, their course began to alter.

The crazed column began to curve across the front of the catedrale, to commence its circumnavigation of the grounds.

Just as they had done at Ebino, when they hurtled pell-mell around the holy carroccio, they now did the same here, so that their clamourous cavorting might sanctify the catedrale. This time, however, they served a different god.

The Church of Nagash was truly re-born!

The Fat Git

Vassal

Nice one. Did you get a new camera? The pictures seem more, er crisper. I like this post very much. Have you created yourwordpress site, if so what is it called?

Padre

Lord

Same camera, but unlike snapping at an ongoing game I can keep retaking til I'm happy so maybe that's why?

Oh yes, my blog is begun. It'll take ages to fully construct, however, as there's a LOT of stuff and I need to upload and edit in all missing 1000 campaign pictures, plus edit text etc to make it work on Wordpress.

See www.bigsmallworlds.com

BTW, how does a person get a blog listed here in a news-feedy sort of way. I've tried to understand the instructions, honest, but am left confused and befuddled.

Oh yes, my blog is begun. It'll take ages to fully construct, however, as there's a LOT of stuff and I need to upload and edit in all missing 1000 campaign pictures, plus edit text etc to make it work on Wordpress.

See www.bigsmallworlds.com

BTW, how does a person get a blog listed here in a news-feedy sort of way. I've tried to understand the instructions, honest, but am left confused and befuddled.

Padre

Lord

I am working my way (slowly) through the campaign posts, editing for grammar, so that I can then transfer them to the BigSmall site. It means, however, that the campaign here is simultaneously becoming slightly more readable! I've got to page 7, Trantio Tested (Bat Rep) so far. It is taking weeks as RL won't allow me to sit for the hundreds of hours this is going to take all in one go. Unsurprisingly.

Still, I am now more confident about the campaign record. I want it to be as accessible and readable as I can make it. One day I'll complete this massive task and actually go back to running the campaign!!!!

Still, I am now more confident about the campaign record. I want it to be as accessible and readable as I can make it. One day I'll complete this massive task and actually go back to running the campaign!!!!

Thantsants

Baron

Good to see you still going strong Padre!

We were talking about you at BOYL and reminiscing about that great game you ran at the first one. Shame we haven't seen you down there since although understand about work getting in the way and all that.

By the way I've moved from York to Cumbria so won't bump in to you at work again I'm afraid!

We were talking about you at BOYL and reminiscing about that great game you ran at the first one. Shame we haven't seen you down there since although understand about work getting in the way and all that.

By the way I've moved from York to Cumbria so won't bump in to you at work again I'm afraid!

Padre

Lord

Good to hear from you Thantsants.

I have been forced to adopt a 'pretend it's not happening' stance to BOYL as a method of dealing with the fact that I keep missing it. Ironically, this year was the first time one of my Skipton Castle work weekends didn't get in the way of attending - instead it was the fact that the BOYL weekend took place during the one Scotland-England school holiday cross-over period that allowed my two little boys to have a summer holiday time with their only cousin. (I got back from Glasgow yesterday.) I seem forever doomed to be unable to attend. Thus I try to focus on my own campaign and, like I said, pretend I'm not missing out! Besides, when the boys get older, including their cousin, I intend to play Warhammer with them during those breaks!

I knew you had moved, as I have been to your school since and learned of your 'activities'. Broke a leg during the move, I heard.

I shall plough on in the hope that one day I will be able to attend, and sort out another large/odd scenario for a WFB 3rd battle. Although I might opt for 6th ed, which I now think was my favourite edition, even though I've been playing since 1st edition.

I have been forced to adopt a 'pretend it's not happening' stance to BOYL as a method of dealing with the fact that I keep missing it. Ironically, this year was the first time one of my Skipton Castle work weekends didn't get in the way of attending - instead it was the fact that the BOYL weekend took place during the one Scotland-England school holiday cross-over period that allowed my two little boys to have a summer holiday time with their only cousin. (I got back from Glasgow yesterday.) I seem forever doomed to be unable to attend. Thus I try to focus on my own campaign and, like I said, pretend I'm not missing out! Besides, when the boys get older, including their cousin, I intend to play Warhammer with them during those breaks!

I knew you had moved, as I have been to your school since and learned of your 'activities'. Broke a leg during the move, I heard.

I shall plough on in the hope that one day I will be able to attend, and sort out another large/odd scenario for a WFB 3rd battle. Although I might opt for 6th ed, which I now think was my favourite edition, even though I've been playing since 1st edition.

Thantsants

Baron

Yep - a week before moving! Long story which I won't clutter your thread up with!

6th ed certainly works well for getting things moving in those bigger games - I'll keep following your campaign here in the hope of seeing you down at Foundry one year!

6th ed certainly works well for getting things moving in those bigger games - I'll keep following your campaign here in the hope of seeing you down at Foundry one year!

Padre

Lord

The end of Spring, IC2403

Part 1. (Excerpt from) A New Scripture for the Enlightened. Chapter 14, The Devoted of Palomtrina

It came to pass in the Spring of that year that the righteous of Palomtrina arose, after the last of the desert men had departed, and this multitude did cry out and promise themselves to Morr, desiring to be holy in his eyes, for they feared the imminent arrival of the undead and the brutes. Vallerius is the name of he who led them, their shepherd. And they did name themselves Morr’s Devoted. And their shepherd commanded them that they offer a sacrifice to the Lord Morr, which they did, putting off all their ornaments, burning and destroying utterly all the dainty works they had amassed, yielding their worldly wealth, offering up every gold and silver bauble they possessed unto the holy church. After which, the people lifted up their voices and wept with joy.

But they knew not that the chief among them, Shepherd Vallerius, was false, and through greed sinned against the Lord Morr, taking what he pleased from that which the Devoted had offered, diminishing its value greatly and concealing that which he had taken. And still his greed was not sated, so he spake unto them and bore false witness, revealing that the Lord Morr had visited his dreams, and he beguiled them with his words, and he revelled in their admiration, and his pride swelled unbounded. He commanded that they slay all those who had tended to the desert men before they departed, be they the innkeepers who had fed them …

… or merely their servants, even the children.

And he commanded them to show no mercy to those men who had traded goods with them …

… and to slay all the women who had known the desert men, then to plunder all that these people possessed, gifting the spoil to the leaders of the Devoted, that they might use it to procure arms and armour for the holy war. In their fury and fervour, the Devoted did shed the blood of the innocent, stoning them with stones and burning them with fire, and utterly destroying them, man and woman, child and infant, not knowing that those things the shepherd had accused the people of were not sins in the eyes of Morr. And their hands were filled with blood. Yet they showed no mercy, despite the pleading of those they slew. And when the righteous priests tried to teach them the error of their ways, and were wroth with them, they did even slay them.

And they did spoil and plunder even as their prey lay dying, taking ox and sheep and ass, and all the goods they had stored, and all that was good in their eyes.

And when they gave thanks their prayers were in earnest, and they cried out for guidance that they might know what they should now do.

Holy Morr looked upon them and knew them to be his Devoted, despite that they were lied to by their false Shepherd. He knew that they had not forsaken him, though they were a trouble unto him. They were made unclean not of themselves, but by he who misled them, yet they could be made clean, ceasing to do all evil. And so Morr visited the shepherd in dreams, and troubled his spirit. And when the sleep broke from him the shepherd knew what must come to pass thereafter, and he was astonied, and at first knew not what to do, for the dream did make him afraid. So Morr took his hand to conduct him whither he was bound, and in turn the shepherd led his congregation to Remas, both he and they in dazed obedience.

Upon the journey the Devoted murmured amongst themselves, for they could see the consternation of their shepherd, and they were troubled by their thoughts, and Morr visited their dreams too that they might grow to suspect their shepherd and know him for what he was. And when they came to Remas they had come to know that Vallerius was a false prophet, and they bound him in fetters and delivered him into the hands of the Admonitor, that he might be judged according to the multitude of his sins, and that they too, in all humility, might be punished for the abominations they had done, for they knew they could not enter Morr’s garden carrying the burden of their sinfulness.

So they did scourge their flesh with flails and whips, the better to tear away their sins through painful subjection to Morr’s will. And for every blow they had struck against the innocent they administered a dozen blows unto their own bodies, in penance, and through this mortification they did purify themselves, and wash away all pride and arrogance, and all sinful thoughts.

And Morr revealed his wrath against the ungodly and unrighteous shepherd to the Admonitor, being the right-hand man of Father Carradalio, and made it known that Shepherd Vallerius must be punished for his iniquities. And the shepherd was taken to the field by the ruins of the Ludus Carracallus, in the company of several brothers of the Disciplinati di Morr, whom the Admonitor had declared to be blessed revengers fit to execute wrath upon him that hath done such evil.

In that place the shepherd knelt, for he could not stand before Morr’s indignation, and he knew full well what he had done and desired that he might be saved by Morr’s mercy. And he was pitiful in the brothers’ eyes. And prayers were said over him as he knelt, that his body might rest peacefully and that such a sinful soul as he would not rise from the grave to commit further wickedness.

While the brothers watched and waited for the appointed time, the shepherd’s vileness did reveal itself for he began to curse them, that they be punished for what they were doing, but they did not revile him in return for they knew from his words that he had been judged righteously, and so took comfort that it was indeed Morr’s will that was to be done.

And when the time came they smote him through his neck, and the blade went out at his throat.

And when an hour had passed, the Devoted were brought to the place of execution. There the Admonitor delivered his admonishment, saying Hear my speech, and hearken to all my words. Your deeds may well have been inspired by Morr, howsoever misinterpreted by Shepherd Vallerius, who in his arrogance feigned an intimacy with Morr he did not possess. I have no doubt that you were driven by an earnest desire to serve Morr Most High, to cleanse both yourselves and the world of all that offends him, and so you sinned in ignorance. It was Vallerius who caused thee to err, but err you did, and you will be judged. What you did was evil in the eyes of Morr and you must pray for forgiveness as you have never prayed before, and you must learn humility in the face of Morr, and bow to the wisdom of those who are closest to him, and who hear his words most clearly.

Holy Morr does not whisper to our Holy Father Carradalio, but speaks loud and clear. You must not presume to know, from your own imaginings and convictions, what is right, nor what must be done, but rather must become fully obedient to the true church and its saints. You must prostrate yourselves before Morr’s altars, humble yourselves before his shrines, and offer yourselves body and soul into his service.

I shall hereby make atonement for your sins, and I will ask that Holy Morr forgive you, so that you may make afresh your covenant with Holy Morr.

And the holiest of books was brought to him that he might read from it and so bless them.

And a priest did intone the necessary prayers before the reading.

Beside him was the Blessed Ravern Standard that the Devoted were to pledge themselves to, as well as several of the most humble and holy priests of Remas …

And the throng of the Devoted did listen unto the words and their hearts were lifted as they knew that they were cleansed of their sins in the eyes of the Lord Morr, and that their hearts were delivered of all tribulations, so that they might now go forth and fight against the vampires and their foul servants until they had gotten the victory over them.

They were given a new Shepherd Marshall to govern them, and to lead them in battle. And the spirit of Morr filled them, until they cried as one, “Thanks be to Morr!”

Part 1. (Excerpt from) A New Scripture for the Enlightened. Chapter 14, The Devoted of Palomtrina

It came to pass in the Spring of that year that the righteous of Palomtrina arose, after the last of the desert men had departed, and this multitude did cry out and promise themselves to Morr, desiring to be holy in his eyes, for they feared the imminent arrival of the undead and the brutes. Vallerius is the name of he who led them, their shepherd. And they did name themselves Morr’s Devoted. And their shepherd commanded them that they offer a sacrifice to the Lord Morr, which they did, putting off all their ornaments, burning and destroying utterly all the dainty works they had amassed, yielding their worldly wealth, offering up every gold and silver bauble they possessed unto the holy church. After which, the people lifted up their voices and wept with joy.

But they knew not that the chief among them, Shepherd Vallerius, was false, and through greed sinned against the Lord Morr, taking what he pleased from that which the Devoted had offered, diminishing its value greatly and concealing that which he had taken. And still his greed was not sated, so he spake unto them and bore false witness, revealing that the Lord Morr had visited his dreams, and he beguiled them with his words, and he revelled in their admiration, and his pride swelled unbounded. He commanded that they slay all those who had tended to the desert men before they departed, be they the innkeepers who had fed them …

… or merely their servants, even the children.

And he commanded them to show no mercy to those men who had traded goods with them …

… and to slay all the women who had known the desert men, then to plunder all that these people possessed, gifting the spoil to the leaders of the Devoted, that they might use it to procure arms and armour for the holy war. In their fury and fervour, the Devoted did shed the blood of the innocent, stoning them with stones and burning them with fire, and utterly destroying them, man and woman, child and infant, not knowing that those things the shepherd had accused the people of were not sins in the eyes of Morr. And their hands were filled with blood. Yet they showed no mercy, despite the pleading of those they slew. And when the righteous priests tried to teach them the error of their ways, and were wroth with them, they did even slay them.

And they did spoil and plunder even as their prey lay dying, taking ox and sheep and ass, and all the goods they had stored, and all that was good in their eyes.

And when they gave thanks their prayers were in earnest, and they cried out for guidance that they might know what they should now do.

Holy Morr looked upon them and knew them to be his Devoted, despite that they were lied to by their false Shepherd. He knew that they had not forsaken him, though they were a trouble unto him. They were made unclean not of themselves, but by he who misled them, yet they could be made clean, ceasing to do all evil. And so Morr visited the shepherd in dreams, and troubled his spirit. And when the sleep broke from him the shepherd knew what must come to pass thereafter, and he was astonied, and at first knew not what to do, for the dream did make him afraid. So Morr took his hand to conduct him whither he was bound, and in turn the shepherd led his congregation to Remas, both he and they in dazed obedience.

Upon the journey the Devoted murmured amongst themselves, for they could see the consternation of their shepherd, and they were troubled by their thoughts, and Morr visited their dreams too that they might grow to suspect their shepherd and know him for what he was. And when they came to Remas they had come to know that Vallerius was a false prophet, and they bound him in fetters and delivered him into the hands of the Admonitor, that he might be judged according to the multitude of his sins, and that they too, in all humility, might be punished for the abominations they had done, for they knew they could not enter Morr’s garden carrying the burden of their sinfulness.

So they did scourge their flesh with flails and whips, the better to tear away their sins through painful subjection to Morr’s will. And for every blow they had struck against the innocent they administered a dozen blows unto their own bodies, in penance, and through this mortification they did purify themselves, and wash away all pride and arrogance, and all sinful thoughts.

And Morr revealed his wrath against the ungodly and unrighteous shepherd to the Admonitor, being the right-hand man of Father Carradalio, and made it known that Shepherd Vallerius must be punished for his iniquities. And the shepherd was taken to the field by the ruins of the Ludus Carracallus, in the company of several brothers of the Disciplinati di Morr, whom the Admonitor had declared to be blessed revengers fit to execute wrath upon him that hath done such evil.

In that place the shepherd knelt, for he could not stand before Morr’s indignation, and he knew full well what he had done and desired that he might be saved by Morr’s mercy. And he was pitiful in the brothers’ eyes. And prayers were said over him as he knelt, that his body might rest peacefully and that such a sinful soul as he would not rise from the grave to commit further wickedness.

While the brothers watched and waited for the appointed time, the shepherd’s vileness did reveal itself for he began to curse them, that they be punished for what they were doing, but they did not revile him in return for they knew from his words that he had been judged righteously, and so took comfort that it was indeed Morr’s will that was to be done.

And when the time came they smote him through his neck, and the blade went out at his throat.

And when an hour had passed, the Devoted were brought to the place of execution. There the Admonitor delivered his admonishment, saying Hear my speech, and hearken to all my words. Your deeds may well have been inspired by Morr, howsoever misinterpreted by Shepherd Vallerius, who in his arrogance feigned an intimacy with Morr he did not possess. I have no doubt that you were driven by an earnest desire to serve Morr Most High, to cleanse both yourselves and the world of all that offends him, and so you sinned in ignorance. It was Vallerius who caused thee to err, but err you did, and you will be judged. What you did was evil in the eyes of Morr and you must pray for forgiveness as you have never prayed before, and you must learn humility in the face of Morr, and bow to the wisdom of those who are closest to him, and who hear his words most clearly.

Holy Morr does not whisper to our Holy Father Carradalio, but speaks loud and clear. You must not presume to know, from your own imaginings and convictions, what is right, nor what must be done, but rather must become fully obedient to the true church and its saints. You must prostrate yourselves before Morr’s altars, humble yourselves before his shrines, and offer yourselves body and soul into his service.

I shall hereby make atonement for your sins, and I will ask that Holy Morr forgive you, so that you may make afresh your covenant with Holy Morr.

And the holiest of books was brought to him that he might read from it and so bless them.

And a priest did intone the necessary prayers before the reading.

Beside him was the Blessed Ravern Standard that the Devoted were to pledge themselves to, as well as several of the most humble and holy priests of Remas …

And the throng of the Devoted did listen unto the words and their hearts were lifted as they knew that they were cleansed of their sins in the eyes of the Lord Morr, and that their hearts were delivered of all tribulations, so that they might now go forth and fight against the vampires and their foul servants until they had gotten the victory over them.

They were given a new Shepherd Marshall to govern them, and to lead them in battle. And the spirit of Morr filled them, until they cried as one, “Thanks be to Morr!”

Padre

Lord

The End of Spring, IC2403

Part 2. A Letter from Antonio Mugello to my most noble Lord Lucca Vescucci of Verezzo

Forgive me, my lord, for the untidiness of my writing, but I am forced by circumstances to pen this missive both in haste and in conditions unconducive to neatness. For the first time in a long while I am not far from Verezzo, being merely a league south of Ridraffa, but the joy I should feel about my proximity to home is diminished by the news I send.

The brute tyrant, Razger Boulderguts, led his army from the beating he received south of Remas, travelling along the Via Diocleta. Neither the Remans nor the Pavonans sought to pursue him, for the former seemed happy enough that he had turned away from their realm, and the latter were in no fit state to attempt any further action in the field. Boulderguts retained the great train of loot he had plundered from Astiano and Pavona, as well as much of his strength. Indeed, it might even be that his own army has swelled in size, for whereas before the double army bore both his and Mangler’s standards at its fore, it is now reported that only Boulderguts’ colours are carried, and that the part of Mangler’s army remaining, still a substantial force, does not baulk at marching under those colours. Several brutes’ corpses were discovered in the army’s wake, some showing signs that they died from festering wounds received at the battle of Diocleta, but others, being the mightier sort, bearing fresh wounds apparently received in some internecine strife. Such evidences most likely indicate that Razger has wrested complete command of the entire force for himself.

Taking leave of the Reman and Pavonan army in Frascoti, I followed the brutes with several scouts, until I joined a party of Verezzan merchants seeking a safe way home. Upon learning that I was your servant, the chief amongst these merchants, your friend Alessandro Burlemacchi, offered whatever I needed to assist me in my duties, and so enabled me to ride close to the brute army in the company of his best guards, all the better to spy upon them. It soon became clear that Razger was not disheartened by his bloody brush with the dukes Guidobaldo and Scaringella, but instead sought to continue his spate of destruction and butchery. As his army approached Ridraffa, the bulging baggage train came to a halt whilst his grey-skinned warriors surged onwards in battle array.

The Ridraffans had made great efforts to fortify their walled city, circumvallating the entire periphery with earthworks and the ditches from which they were dug, defences which were both palisaded and studded with a forest of storm-poles. It seemed to me that the brutes would be sorely tried in the taking of the city, if even only a meagre garrison were available to man the works. But I did watch with mine own eyes as they marched on without once faltering, then surged over the works with no discernible delay.

The populace fled pell-mell from every gate, for the most part unburdened with possessions and goods, as if they had learned full well from the cruel fate of those towns and cities already fallen. Indeed, perhaps the only reason so many did escape was because they left their wealth, even their livestock, behind, for in so doing the brutes were consequently distracted, being fully occupied with the sharing of the spoils.

I myself met with several of those who fled, including Master Poliziano, secretary to the city council and cousin to the gonfalonieri. It was from him I first learned the terrible truth concerning how the city had fallen so suddenly, an account which sadly has been verified by others I have met since.

The garrison was weak, certainly in comparison to Razger’s force, but their defensive works were strong, and they had a card to play which the Ridraffans believed could save them – none other than the Wizard Lord Salvatore. All in Tilea know that when the ratto uomo swarm threatened to swallow Ridraffa in 2381, Gervasio Strozzi conjured magics so powerful that nigh upon half the swarm burned causing the rest to flee in fear, thus earning himself his new name.

Yet it was not to be so this time. Ancient as he was, his beard reputedly the longest and whitest born by any man south of the River Trantino, his bravery was undiminished. Indeed, perhaps he was too brave? For he was heard to say, “I need to get a little closer,” and before anyone could stop him he stepped outside the works.

All those present fell silent, apart from one horn-blower who was so intent upon sounding his call to arms that he alone did not notice, despite being one of those closest to Salvatore.

Staff in hand, his large, crooked, green hat ensuring that every pair of ogre eyes could pick him out easily (especially when they sought out the blaring horn) he strode beyond even the storm poles. Perhaps he had become purblind in his old age? Or was so engrossed in his ethereal conjurations that he lost sight of this world and the many, mundane dangers it held in that moment? The soldiers stared in confusion …

… as he spoke the words of his incantation. Those who saw it told me that upon completion, and the bringing down of his staff, for a moment it was as if the world stood still. And yet, the sky remained calm – not one wisp of cloud appeared, not the tiniest flicker of lightning, nor even the faintest echo of distant thunder.

The brutes had halted, perhaps as surprised as the Ridraffans, to join the momentary silence.

Then one was heard to laugh, and another to shout, and then many more gave vent to angry cries, and they loosed a rain of missiles upon the old wizard: a spear-sized quarrel, a hail of leadshot and a whole mess of mangled metal. Inevitably, in the midst of it all, as the grassy ground churned about him and the storm poles at his side shivered to pieces, he fell.

Then, as suddenly as the horn fell silent, it’s blower belatedly aware of what was happening, the brute army lurched forwards. To their credit, I was told that not one Ridraffan fled, but instead they chose to fight, running from those parts of the works unthreatened by the foe to where the attack was to come.

They loosed a hundred bolts, and drew every sword …

… but to no avail, for the foe burst through the storm-poles as if leaping nothing more than toothpicks, and mounted the works as if they were but molehills, and there was nothing the defenders could do to stop them.

In this way Ridraffa fell, every fighting man brutally slain and crushed under the heavy, iron-shod feet.

Against the advice of the guards with me, and yet with their brave acceptance of my decision, I lingered in the vicinity of the city, intent upon discovering the ogres’ intentions, whither they would go, for I was filled with dread at the prospect that they might choose to travel further south and so threaten your Lordship’s realm.

Razgers’ already huge baggage train swelled further as everything of value was dragged from Ridraffa. The ogres pressed every cart and wain, every carriage and coach, into their service, and still it was not enough (for many such conveyances had left the city in the days before their arrival). And so along with their greenskin servants they cobbled together carts of their own, taking wheels from barrows and gun-carriages, from the wrecked remains of abandoned wagons and the newly made stocks in the wheelwright’s workshops.

I myself saw them, through a perspective glass, as they left the city gates, their myriad means of transport, a hotch-potch of creaking and rattling contraptions, hauled by everything from livestock to slaves and even ogres.

I watched as long as I could, until my guards dragged me away for my own protection, and I can report only that they were obviously heading for the bridge over the River Riatti. What Razger intends once they have crossed, whether to travel further south towards Spomanti and thus threaten the whole of your realm, or to turn north once more, perhaps finally sated by their vast haul of plunder, I know not. I could not cross the bridge for they left several brutes upon it, perhaps as a rear guard, perhaps because not all their force has yet to depart Ridraffa.

Thus it is that am dispatching this letter to you, and two identical copies by different messengers to ensure its arrival, rather than carrying it myself. I intend to cross the bridge at the first opportunity, to continue following the brute army, and to learn as much as possible of their intentions.

I hope and pray that my next missive will bear good news. Your loyal and humble servant, Antonio Mugello.

Game Notes:

This story was derived from a battle and the events around it. I didn’t write a full report, however, as it was a quick game (taking the time for lots of pictures and notes was impossible) and it didn’t seem ‘interesting’ enough, in that we both knew who would win. A part of me was glad I didn’t take detailed notes because I made a shocking and stupid decision in the first turn which, without a doubt, cost me the game – or at the least to the chance to do any significant damage to the ogres.

Jamie is the campaign participant playing Razger Boulderguts, while I (campaign GM) commanded the NPC force defending the small city of Ridraffa. I had modelled some new defences for the city, to expand those I had already made, and I used some newly painted generic militia figures as part of the defending force. When I realised 850 points was trying to take a nearly 3000 pt enemy, I thought to game was pointless, but then I remembered that the players ‘ realms and major NPC realms were allowed to have a free ‘ruler lord’. So I decided that the Ridraffans could have a level 3 Wizard lord too. Combined with sturdy defences then … Game on!

Except, as described in Mugello’s letter above, in the first turn I decided to risk walking the wizard out to get within range to attempt chain lightning. I thought I needed to maximise the number of chances I had that magic might swing in my favour.

Here is a shot of the moment from the actual game …

I didn't take into account the scraplauncher, pistol-toting Maneaters and the Hunter with giant crossbow. I should have done.

Needless to say, it did not go well. Salvatore could not save himself (ironic) and died. And the ogres walked the rest of it. The only real harm the Ridraffans managed was to destroy the last of the ogre’s leadbelchers, to the point where the unit couldn’t recover. Considering, however, that the loot gained from razing such a small city could buy the lost Leadbelchers several times over, I doubt Jamie minded.

Still, it made writing the brief account above easy, and it wasn’t a run of the mill sort of battle!

Part 2. A Letter from Antonio Mugello to my most noble Lord Lucca Vescucci of Verezzo

Forgive me, my lord, for the untidiness of my writing, but I am forced by circumstances to pen this missive both in haste and in conditions unconducive to neatness. For the first time in a long while I am not far from Verezzo, being merely a league south of Ridraffa, but the joy I should feel about my proximity to home is diminished by the news I send.

The brute tyrant, Razger Boulderguts, led his army from the beating he received south of Remas, travelling along the Via Diocleta. Neither the Remans nor the Pavonans sought to pursue him, for the former seemed happy enough that he had turned away from their realm, and the latter were in no fit state to attempt any further action in the field. Boulderguts retained the great train of loot he had plundered from Astiano and Pavona, as well as much of his strength. Indeed, it might even be that his own army has swelled in size, for whereas before the double army bore both his and Mangler’s standards at its fore, it is now reported that only Boulderguts’ colours are carried, and that the part of Mangler’s army remaining, still a substantial force, does not baulk at marching under those colours. Several brutes’ corpses were discovered in the army’s wake, some showing signs that they died from festering wounds received at the battle of Diocleta, but others, being the mightier sort, bearing fresh wounds apparently received in some internecine strife. Such evidences most likely indicate that Razger has wrested complete command of the entire force for himself.

Taking leave of the Reman and Pavonan army in Frascoti, I followed the brutes with several scouts, until I joined a party of Verezzan merchants seeking a safe way home. Upon learning that I was your servant, the chief amongst these merchants, your friend Alessandro Burlemacchi, offered whatever I needed to assist me in my duties, and so enabled me to ride close to the brute army in the company of his best guards, all the better to spy upon them. It soon became clear that Razger was not disheartened by his bloody brush with the dukes Guidobaldo and Scaringella, but instead sought to continue his spate of destruction and butchery. As his army approached Ridraffa, the bulging baggage train came to a halt whilst his grey-skinned warriors surged onwards in battle array.

The Ridraffans had made great efforts to fortify their walled city, circumvallating the entire periphery with earthworks and the ditches from which they were dug, defences which were both palisaded and studded with a forest of storm-poles. It seemed to me that the brutes would be sorely tried in the taking of the city, if even only a meagre garrison were available to man the works. But I did watch with mine own eyes as they marched on without once faltering, then surged over the works with no discernible delay.

The populace fled pell-mell from every gate, for the most part unburdened with possessions and goods, as if they had learned full well from the cruel fate of those towns and cities already fallen. Indeed, perhaps the only reason so many did escape was because they left their wealth, even their livestock, behind, for in so doing the brutes were consequently distracted, being fully occupied with the sharing of the spoils.

I myself met with several of those who fled, including Master Poliziano, secretary to the city council and cousin to the gonfalonieri. It was from him I first learned the terrible truth concerning how the city had fallen so suddenly, an account which sadly has been verified by others I have met since.

The garrison was weak, certainly in comparison to Razger’s force, but their defensive works were strong, and they had a card to play which the Ridraffans believed could save them – none other than the Wizard Lord Salvatore. All in Tilea know that when the ratto uomo swarm threatened to swallow Ridraffa in 2381, Gervasio Strozzi conjured magics so powerful that nigh upon half the swarm burned causing the rest to flee in fear, thus earning himself his new name.

Yet it was not to be so this time. Ancient as he was, his beard reputedly the longest and whitest born by any man south of the River Trantino, his bravery was undiminished. Indeed, perhaps he was too brave? For he was heard to say, “I need to get a little closer,” and before anyone could stop him he stepped outside the works.

All those present fell silent, apart from one horn-blower who was so intent upon sounding his call to arms that he alone did not notice, despite being one of those closest to Salvatore.

Staff in hand, his large, crooked, green hat ensuring that every pair of ogre eyes could pick him out easily (especially when they sought out the blaring horn) he strode beyond even the storm poles. Perhaps he had become purblind in his old age? Or was so engrossed in his ethereal conjurations that he lost sight of this world and the many, mundane dangers it held in that moment? The soldiers stared in confusion …

… as he spoke the words of his incantation. Those who saw it told me that upon completion, and the bringing down of his staff, for a moment it was as if the world stood still. And yet, the sky remained calm – not one wisp of cloud appeared, not the tiniest flicker of lightning, nor even the faintest echo of distant thunder.

The brutes had halted, perhaps as surprised as the Ridraffans, to join the momentary silence.

Then one was heard to laugh, and another to shout, and then many more gave vent to angry cries, and they loosed a rain of missiles upon the old wizard: a spear-sized quarrel, a hail of leadshot and a whole mess of mangled metal. Inevitably, in the midst of it all, as the grassy ground churned about him and the storm poles at his side shivered to pieces, he fell.

Then, as suddenly as the horn fell silent, it’s blower belatedly aware of what was happening, the brute army lurched forwards. To their credit, I was told that not one Ridraffan fled, but instead they chose to fight, running from those parts of the works unthreatened by the foe to where the attack was to come.

They loosed a hundred bolts, and drew every sword …

… but to no avail, for the foe burst through the storm-poles as if leaping nothing more than toothpicks, and mounted the works as if they were but molehills, and there was nothing the defenders could do to stop them.

In this way Ridraffa fell, every fighting man brutally slain and crushed under the heavy, iron-shod feet.

Against the advice of the guards with me, and yet with their brave acceptance of my decision, I lingered in the vicinity of the city, intent upon discovering the ogres’ intentions, whither they would go, for I was filled with dread at the prospect that they might choose to travel further south and so threaten your Lordship’s realm.

Razgers’ already huge baggage train swelled further as everything of value was dragged from Ridraffa. The ogres pressed every cart and wain, every carriage and coach, into their service, and still it was not enough (for many such conveyances had left the city in the days before their arrival). And so along with their greenskin servants they cobbled together carts of their own, taking wheels from barrows and gun-carriages, from the wrecked remains of abandoned wagons and the newly made stocks in the wheelwright’s workshops.

I myself saw them, through a perspective glass, as they left the city gates, their myriad means of transport, a hotch-potch of creaking and rattling contraptions, hauled by everything from livestock to slaves and even ogres.

I watched as long as I could, until my guards dragged me away for my own protection, and I can report only that they were obviously heading for the bridge over the River Riatti. What Razger intends once they have crossed, whether to travel further south towards Spomanti and thus threaten the whole of your realm, or to turn north once more, perhaps finally sated by their vast haul of plunder, I know not. I could not cross the bridge for they left several brutes upon it, perhaps as a rear guard, perhaps because not all their force has yet to depart Ridraffa.

Thus it is that am dispatching this letter to you, and two identical copies by different messengers to ensure its arrival, rather than carrying it myself. I intend to cross the bridge at the first opportunity, to continue following the brute army, and to learn as much as possible of their intentions.

I hope and pray that my next missive will bear good news. Your loyal and humble servant, Antonio Mugello.

Game Notes:

This story was derived from a battle and the events around it. I didn’t write a full report, however, as it was a quick game (taking the time for lots of pictures and notes was impossible) and it didn’t seem ‘interesting’ enough, in that we both knew who would win. A part of me was glad I didn’t take detailed notes because I made a shocking and stupid decision in the first turn which, without a doubt, cost me the game – or at the least to the chance to do any significant damage to the ogres.

Jamie is the campaign participant playing Razger Boulderguts, while I (campaign GM) commanded the NPC force defending the small city of Ridraffa. I had modelled some new defences for the city, to expand those I had already made, and I used some newly painted generic militia figures as part of the defending force. When I realised 850 points was trying to take a nearly 3000 pt enemy, I thought to game was pointless, but then I remembered that the players ‘ realms and major NPC realms were allowed to have a free ‘ruler lord’. So I decided that the Ridraffans could have a level 3 Wizard lord too. Combined with sturdy defences then … Game on!

Except, as described in Mugello’s letter above, in the first turn I decided to risk walking the wizard out to get within range to attempt chain lightning. I thought I needed to maximise the number of chances I had that magic might swing in my favour.

Here is a shot of the moment from the actual game …

I didn't take into account the scraplauncher, pistol-toting Maneaters and the Hunter with giant crossbow. I should have done.

Needless to say, it did not go well. Salvatore could not save himself (ironic) and died. And the ogres walked the rest of it. The only real harm the Ridraffans managed was to destroy the last of the ogre’s leadbelchers, to the point where the unit couldn’t recover. Considering, however, that the loot gained from razing such a small city could buy the lost Leadbelchers several times over, I doubt Jamie minded.

Still, it made writing the brief account above easy, and it wasn’t a run of the mill sort of battle!

Padre

Lord

The End of Spring, IC2403

3. Shooting at the Butts

(Terrene, part of the city state of Verezzo)

At Poliena, the largest settlement in Terrene, that part of the city state of Verezzo inhabited almost wholly by halflings, the afternoon was as pleasant as could be expected. Three regulars were taking in the sun outside the Hairy Hog alehouse, supping of the best the landlord had to offer. In many ways, for them, this was no different to any other afternoon, except that they were dressed in blue and yellow livery, and had a very important visitor.

Pablo was drinking deep of his cup, so that ale ran down his chin.

“Best not over do it,” suggested Tino. “We have to put on a good show.”

Pablo, who heard him, continued to gulp down his ale, while Benneto, who was not listening, stared absently at what was happening on the green. Tino watched with raised eyebrows until Pablo drained his tankard then slammed it down on the table.

After wiping his chin with the back of his hand, Pablo hiccuped, then gave a silly smile. Tino’s brow furrowed, which made Pablo smile all the more. He threw in a chuckle for good measure.

“I heard you,” Pablo said, before Tino could give vent to the inevitable complaint. “I just think my shooting’s better with a belly full. Steadies my aim, see?”

“Makes you care less about your aim, you mean," said Tino. “You’re lucky Lord Vescucci is twice your height otherwise he'd smell the ale on your breath.”

“But all soldiers drink before battle.”

“Ha! This ain’t battle. This is us showing our lord what we can do.”

The silly smile reappeared on Pablo’s face. “All’s well and good then, ‘cos drinking’s what I do best,” he said.

The word ‘battle’ had jolted Benneto out of his dreamy daze. His brow furrowed. “You think we really will have to fight?” he asked.

“Ridraffa’s fallen, so it’s likely we’re next,” explained Tino. “Boulderguts has ravaged his way through Tilea. Why would he suddenly decide to stop unless someone stops him?”

“But no-one has stopped him, neither Pavonans or Remans, and not for want of trying.”

“That they haven’t,” agreed Tino, somberly. “But they must have hurt him.”

“How can you know that?” demanded Bennetto.

“I know because he did not try to take the city of Remas, where gold is piled high. And they say he passed through Frascoti in such a hurry that his brutes took barely anything from it.”

“But they didn’t rush by Ridraffa, did they?” argued Benetto. “They bashed everyone’s heads in and took all they could. Which is a lot.”

"Ridraffa isn’t Verezzo," said Tino. "We have an army, they only had some militia and a handful of mercenaries.”

“Oh aye, an army that includes us. Great!” said Benetto. He plucked an arrow from his quiver and laid it on the table. “Will our shafts even pierce the brutes' flesh deep enough for them to notice?”

“We’ll just have to see, won’t we? The only alternatives are to run away from our homes, or wait to be served on their platters.”

The three fell silent for a moment, then Pablo piped up.

“Best have another ale then? While we can.”

…

Upon the green before them a company of archers were already letting loose at the butts. They too were liveried, apart from the hunter Roberto Cappuccio, known to all his friends as Pettirosso, who always favoured green despite his nickname.

Their weapons looked like longbows would in a man’s hand, yet they were no longer than what men called bows. Every fellow there had practiced regularly since youth, honing his skill and strengthening the muscles (moreso on one side of his body than the other). They could match the range and punch of a human bow, but they hit the mark more frequently, and they could generally shoot for longer, provided there was some nourishment to hand to keep their spirits up. And they were just as well practiced at ensuring there was always food to hand.

The village constable, Giusto Corumo, was also watching the practice, his two brothers by his side, his big baton resting on his shoulder.

It was his responsibility to muster the militia, though not to lead them in war. He was the stepping stone that took the able-bodied from the world of peace to field of battle; or more accurately, the short-tempered, foul-mouthed, club bearing elder who roused them, rounded them up and presented them to the military officers. For many a year he had rallied the rabble to ready them for their bi-annual drills, with no shortage of cruel jests to shame them into activity. This morning his tone had been just different enough, however, that nearly every somewhat surprised warrior recognised there was something different going on, and not just because the muster was a little earlier in the season than usual. The constable had also rushed like he had never before done, rousing every eligible soldier from each and every village and hamlet in less than four hours, which was no mean feat for a fellow as stout as he, especially when garbed in an iron breastplate to add to his military countenance. And they were right to be suspicious, for this was no mere holiday drill, this was the real thing. Their Lord, Conte Lucca Vescucci of Verezzo, had summoned them to make ready for war.

The conte had arrived at noon, just as several many of the gathered archers were beginning to hope that the muster was some sort of mistake, and he had immediately asked that the several companies show them what they can do. He had only a small company of guards with him, which included the handful of halflings who attended upon him at court in Verezzo. At first, Lord Lucca seemed uninterested in their drill, but rather wanted to see their skill with their bows. So began an archery tournament lasting the afternoon, which the conte observed intently.

One rank at a time, the halflings came before him, planted their shafts in the ground, then began loosing them at the butts. This would go on until Lord Lucca cried “Enough! Well done. Bring the next.” Then an army of younglings would pluck arrows from the butts while one rank marched as best they could away and another took their place. Always a thorough man, being a natural philosopher and organiser of his realm’s affairs, taking great care over matters of trade, finance and agriculture, studiously acquiring the knowledge he needed to keep his realm prosperous and safe, he was showing the same attention to detail here. As the afternoon lengthened, it became clear he intended to witness the skill of each and every archer, to see for himself whether (to a lad) they could be relied upon.

And as time wore on he seemed to relax somewhat, for rank after rank showed impressive consistency in their aim, peppering the targets’ centres with ever more holes, while leaving the periphery virtually unblemished.

All was done in a leisurely, sedate manner, like a lazy game of stoolball on a late summer’s afternoon, until almost everyone was thinking of the fine evening that must naturally follow this sport, with a pleasant pipe or two and a jar or three of ale.

But the slow pace was due to Lord Lucca’s usual thoroughness, rather than any lack of urgency, and as the last company was dismissed (looking forward to their first drink of the night) he turned to the attending captains and ordered that the whole militia now assemble. He intended to inspect their brigade drill.

…

Within a quarter of an hour the halfling militia had drawn themselves up into two bodies, being four ranks each but arrayed in double width and so presenting as two double length ranks. Each company had its own colour, red and blue, as indicated by their flags' edgings.

Lord Lucca was joined by Barone Iacopo Brunetti, the lord of Poliena. The barone would have cut quite a dash, cloaked and clad in armour upon his stout pony, if it were not for the conte’s contrasting bulk. Still, Iacopo’s pony bucked and reared as if keen for a fight, and he brandished his sword as he gave commands for the captains to repeat.

Once their manoeuvres were done, having doubled their front, countermarched and demonstrated the neatness of their dressings, they halted. The conte, apparently satisfied, now ordered them to stand, and began a short speech.

“You all know why you have been called forth this day. All of Tilea knows of the evils that beset our land - how other cities have suffered indignities at the least, and destruction at the worst. That will not happen to our dear Verezzo, for you and I will not allow it. Today you have proved yourself more than fit for any fight ahead. To a soldier you shoot well, and as a body you are as well drilled as any mercenary, or even any palazzo guard. Long practice has made you this way, and all that effort was done for this day. This e’en, first sharpen your arrowheads and fix your flights; hone your blades and look to all the trappings you need for war. Make these things as fit for battle as your yourselves have proven today to be. Whether brutes come or the unliving, or both, we shall be ready for them, and they shall learn that what is ours cannot be taken from us, and that we will not allow those we love to be harmed. The men of Verezzo and Spomanti, and the halflings of Terrene will stand strong together, each being the best I could hope for, and each complementing the other to forge a fighting force of courage and skill.

“Myrmidia has watched us today, and I know she will be pleased. Tonight, when every edge is as sharp as a razor, every bow waxed and all the armour oiled, say a quiet prayer to dedicate yourselves to her, and ask her to guide both you, your captains and myself in the days and weeks to come. Then, fill your flagons and drink a health in her honour!”

“Evviva!” came the cheer, again and again, as the Alfieri flourished the colours aloft.

3. Shooting at the Butts

(Terrene, part of the city state of Verezzo)

At Poliena, the largest settlement in Terrene, that part of the city state of Verezzo inhabited almost wholly by halflings, the afternoon was as pleasant as could be expected. Three regulars were taking in the sun outside the Hairy Hog alehouse, supping of the best the landlord had to offer. In many ways, for them, this was no different to any other afternoon, except that they were dressed in blue and yellow livery, and had a very important visitor.

Pablo was drinking deep of his cup, so that ale ran down his chin.

“Best not over do it,” suggested Tino. “We have to put on a good show.”

Pablo, who heard him, continued to gulp down his ale, while Benneto, who was not listening, stared absently at what was happening on the green. Tino watched with raised eyebrows until Pablo drained his tankard then slammed it down on the table.

After wiping his chin with the back of his hand, Pablo hiccuped, then gave a silly smile. Tino’s brow furrowed, which made Pablo smile all the more. He threw in a chuckle for good measure.

“I heard you,” Pablo said, before Tino could give vent to the inevitable complaint. “I just think my shooting’s better with a belly full. Steadies my aim, see?”

“Makes you care less about your aim, you mean," said Tino. “You’re lucky Lord Vescucci is twice your height otherwise he'd smell the ale on your breath.”

“But all soldiers drink before battle.”

“Ha! This ain’t battle. This is us showing our lord what we can do.”

The silly smile reappeared on Pablo’s face. “All’s well and good then, ‘cos drinking’s what I do best,” he said.

The word ‘battle’ had jolted Benneto out of his dreamy daze. His brow furrowed. “You think we really will have to fight?” he asked.

“Ridraffa’s fallen, so it’s likely we’re next,” explained Tino. “Boulderguts has ravaged his way through Tilea. Why would he suddenly decide to stop unless someone stops him?”

“But no-one has stopped him, neither Pavonans or Remans, and not for want of trying.”

“That they haven’t,” agreed Tino, somberly. “But they must have hurt him.”

“How can you know that?” demanded Bennetto.

“I know because he did not try to take the city of Remas, where gold is piled high. And they say he passed through Frascoti in such a hurry that his brutes took barely anything from it.”

“But they didn’t rush by Ridraffa, did they?” argued Benetto. “They bashed everyone’s heads in and took all they could. Which is a lot.”

"Ridraffa isn’t Verezzo," said Tino. "We have an army, they only had some militia and a handful of mercenaries.”

“Oh aye, an army that includes us. Great!” said Benetto. He plucked an arrow from his quiver and laid it on the table. “Will our shafts even pierce the brutes' flesh deep enough for them to notice?”

“We’ll just have to see, won’t we? The only alternatives are to run away from our homes, or wait to be served on their platters.”

The three fell silent for a moment, then Pablo piped up.

“Best have another ale then? While we can.”

…

Upon the green before them a company of archers were already letting loose at the butts. They too were liveried, apart from the hunter Roberto Cappuccio, known to all his friends as Pettirosso, who always favoured green despite his nickname.

Their weapons looked like longbows would in a man’s hand, yet they were no longer than what men called bows. Every fellow there had practiced regularly since youth, honing his skill and strengthening the muscles (moreso on one side of his body than the other). They could match the range and punch of a human bow, but they hit the mark more frequently, and they could generally shoot for longer, provided there was some nourishment to hand to keep their spirits up. And they were just as well practiced at ensuring there was always food to hand.

The village constable, Giusto Corumo, was also watching the practice, his two brothers by his side, his big baton resting on his shoulder.

It was his responsibility to muster the militia, though not to lead them in war. He was the stepping stone that took the able-bodied from the world of peace to field of battle; or more accurately, the short-tempered, foul-mouthed, club bearing elder who roused them, rounded them up and presented them to the military officers. For many a year he had rallied the rabble to ready them for their bi-annual drills, with no shortage of cruel jests to shame them into activity. This morning his tone had been just different enough, however, that nearly every somewhat surprised warrior recognised there was something different going on, and not just because the muster was a little earlier in the season than usual. The constable had also rushed like he had never before done, rousing every eligible soldier from each and every village and hamlet in less than four hours, which was no mean feat for a fellow as stout as he, especially when garbed in an iron breastplate to add to his military countenance. And they were right to be suspicious, for this was no mere holiday drill, this was the real thing. Their Lord, Conte Lucca Vescucci of Verezzo, had summoned them to make ready for war.

The conte had arrived at noon, just as several many of the gathered archers were beginning to hope that the muster was some sort of mistake, and he had immediately asked that the several companies show them what they can do. He had only a small company of guards with him, which included the handful of halflings who attended upon him at court in Verezzo. At first, Lord Lucca seemed uninterested in their drill, but rather wanted to see their skill with their bows. So began an archery tournament lasting the afternoon, which the conte observed intently.

One rank at a time, the halflings came before him, planted their shafts in the ground, then began loosing them at the butts. This would go on until Lord Lucca cried “Enough! Well done. Bring the next.” Then an army of younglings would pluck arrows from the butts while one rank marched as best they could away and another took their place. Always a thorough man, being a natural philosopher and organiser of his realm’s affairs, taking great care over matters of trade, finance and agriculture, studiously acquiring the knowledge he needed to keep his realm prosperous and safe, he was showing the same attention to detail here. As the afternoon lengthened, it became clear he intended to witness the skill of each and every archer, to see for himself whether (to a lad) they could be relied upon.

And as time wore on he seemed to relax somewhat, for rank after rank showed impressive consistency in their aim, peppering the targets’ centres with ever more holes, while leaving the periphery virtually unblemished.