You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Tilea IC2401 (Campaign#8)

- Thread starter Padre

- Start date

Lands Annex

Vassal

Yes! Glad to see you back again with such fantastic storytelling.

Padre

Lord

Thanks Grungni and Lands Annex. Next part ...

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Prequel to second assault on Campogrotta

Out Riding

North East of Campogrotta, Very Early Autumn 2403

Having circumnavigated Campogrotta three times, which at over two leagues out from the city meant travelling a considerable distance, the Brabanzon riders were within sight of the rock-strewn area between the villages of Buldio and the Astigo River. They were one of three such scouting bands circling the besieged city in order to discover any approaching relief forces. Lord Narhaz, the ‘great-thane’ commanding the army of Karak Borgo, had every reason to expect the enemy to attempt a relief, for not only was the tyrant Razger Boulderguts reportedly returning to the city having completed his grand (and very profitable) chevauchee, but there were also reports of an ogre garrison at Ravola to the north and smaller forces scattered throughout Campogrotta’s compass. The ogres’ iron grip on the entire realm had relied on gangs of club-wielding brutes to ensure the native citizens’ continually cowed obedience, and any or all of these ogres could be on the move.

Evrart, the longest serving Brabanzon mercenary amongst the riders, his toothless mouth and sunken cheeks belying his sturdy toughness and considerable strength, rode at the head of the little band, regaling his friend Bossu with his latest theory.

“Ask anyone,” he suggested, “even the locals. No-one has ever seen him.”

“Well, wizards like to keep to themselves,” said Bossu.

“Not always. That dwarf Glammerscale’s been riding with Jacquot’s lads, if you can call it riding. He’s full of friendly conversation.”

“Dwarfs aren’t proper wizards, so that don’t prove anything.”

Evrart pondered this a moment. “Alright,” he admitted, “I’ll grant you that. But what about Perette? She doesn’t exactly hide herself away; quite the opposite. Not that I’m complaining.”

“She’s not what you’d call ‘proper’ either,” said Bossu with a grin.

“Well, no. But they’re both just petty wizards. I’m talking about the great ones like Niccolo. They get noticed.”

“Not so,” said Bossu. “Most wizards shut themselves up in a tower or some such place and go about whatever strange wickedness they’ve set their minds to.”

“Perette doesn’t need any tower to be wicked,” joked Evrart, now grinning himself.

Their conversation stopped a moment as they heard a horn from up ahead.

“That’s the others,” said Evrart. He tugged the reigns a little to send his horse, his companions following, in the direction of the sound. Bossu kept by his side and returned to the topic in hand.

“I’m talking about the mighty wizards too. They say Niccolo’s lived more’n twice as long as anyone should hope for or expect, harbouring his grudge until he returned to retake the city with the ogres. No-one had heard of him for decades – everyone thought he was dead. That’s a lot of practice at hiding away. Now he’s returned, maybe he’s trying to finish off whatever it was he was doing before the Campogrottans threw him out?”

“I don’t buy it,” argued Evrart. “If Lord Niccolo really ruled that city, there’d be at least one report of him. Instead everyone talks about the ogres, about Razger and Wurgrut. How they took the city, then took Ravola, then robbed their way through Tilea. Razger gives the orders, his brutes do the damage. I don’t see how Niccolo fits in at all. You saw yourself, Bossu, it was their banners on the city towers, no one elses.”

“Oh, and you know Lord Niccolo’s coat-of-arms do you?”

“No, but I know it isn’t a line of teeth-mountains or a bull’s skull tied to a pole with catgut. He’s a nobleman of an ancient family. All the rulers are here, even the vampires, just like home. It’ll be some flowery leaf or a golden crown or fancy swirls in bright green or red or …”

“You’ve no idea what it is!”

“Ah, but I don’t need to know to make my point. Those banners were ogre banners. The whole realm is ruled by ogres. It’s Razger who leads the armies - he decides what they’ll do – so it’s no surprise that they spend all their time smashing places up and plundering. If Niccolo was some great and mighty wizard kept o’er long in this world by necromancy, then why didn’t he make an appearance on the walls during the assaults? Why didn’t he fling lightning down, or summon the undead to serve in the defence? Brute ogres, that’s all that was seen; blood-spattered shamans waving bloody innards about. That’s all.”

“From what I’ve heard of the assault, I doubt our lads would have noticed some old man amongst the brutes. What’s a flash of lightning here and there when Razger’s lads are shooting cannons like handguns and the walls are tumbling left and right?”

“Well,” said Evrart, “Let us see what’s what when we take the city. I’ll bet you ten silver ecus that there’s no sign of any wizard, nor even that there ever was one besides them butcher-shamans. Wizard Lord Niccolo’s nothing but a story.”

“I’ll take that bet,” said Bossu. “And you’ll pay me as soon as you get your share. I’m not waiting to hear your drunken excuses after you and your purse disappear into the stews for a week.”

The horn-blowing riders were the other half of their own band – led by a veteran called Raol - who had split off earlier in the day to sweep a little further north and so cover more ground, aiming to rendezvous near the strangely shaped black-rock they had camped at on their last circuit. Upon meeting it was immediately apparent the new arrivals did not intend to stop, so the two groups merged to ride as one.

The riders were mounted on good horses, but not destriers like the nobility of Bretonnia favoured in battle, nor palfreys like the same nobles rode when travelling. These horses were best described as rounceys, trained for both long journeys and battle, but not able to support the weight of a plated knight and barding. Each soldier wore a light armour of chainmail and carried long spears, so they could deliver a charge if the opportunity arose, and sported parti-coloured yellow and green shields, being the company’s livery. Every one of them also carried bows and quivers, allowing them to loose volleys at a distance to harry the foe. As they rode now, some clutched their spears, their bows wrapped in waxed linen and slung across either their own back or their mounts; while others held their bows, their spears slotted into long pouches behind their saddles and their shields slung on harness hooks. One or two, Evrart and Raol included, found it more convenient to have both weapons wrapped and bagged while they concentrated on riding and keeping an eye out. They had experience enough to know that should trouble arise, they would have time to prepare whichever weapon they needed, and if they hadn’t time, then they could draw their swords in a moment.

“News, then?” shouted Evrart to Raol, as they both rode at the head of the reconstituted column.

“Aye, and not good. There’s more coming.”

“Razger?”

“Don’t think so,” said Raol. “This lot came from Buldio.”

“Could be some trick of Razger’s, trying to swing around and arrive where he ain’t expected?”

“We thought so too,” said Raol. “So to make sure we got a proper look at them. They’re just a band of bulls, too small in number to be Razger’s army - no warmachines, no baggage, an’ only one banner. I reckon they’ve been off bullying Buldio, but now ordered to return.”

“Could they be meeting with Razger?”

“If that’s their plan, then they’re meeting at Campogrotta. The road they’re taking leads straight there.”

…

(An hour later.)

As they reached the southern stretch of the rocky-ground they spied one of the other two bands of riders heading their way, led by the riders’ commander, Sergeant Huget. The company’s colours were easily made out at the sergeant’s side, long before much else could be seen. Once again the two groups rode towards each other …

… to join each other on the move; and once again Evrart kept his place at the fore, thus joining the sergeant. As they made their way to the path they had found previously, which led through the wide band of rocks bounding the southernmost reach of this stony land, he reported all he had learned to the sergeant. By the time he finished they had entered the gap through the rocks.

“They’re not the only enemy heading this way,” said the sergeant. “We’ve seen more on the Iron Road.”

“Razger?” asked Evrart.

“I don’t think so. They’re much the same as you described, except that there were greenskin runts with this lot too. And they were coming from the east not the west, which is where Razger will come from.”

“They can’t be from the Lugo watchtower, that place was dead. And there’s no way they came down the Iron Road,” said Evrart.

“No, I reckon they came from the villages of Sermide, only they went north to meet the road before they turned west, instead of just going straight to Campogrotta. They might be planning to meet the ones you saw. ‘Twould explain their diversions.”

“They’re bringing everything they can, then?” asked Evrart.

“As to be expected,” said the sergeant.

“So does that mean Razger’s coming too?”

“Who knows? If he is, then the army’s in big trouble because the enemy’s closing from all sides. If he isn’t, then the army still needs to know about this lot because they’re trouble enough.”

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Prequel to second assault on Campogrotta

Out Riding

North East of Campogrotta, Very Early Autumn 2403

Having circumnavigated Campogrotta three times, which at over two leagues out from the city meant travelling a considerable distance, the Brabanzon riders were within sight of the rock-strewn area between the villages of Buldio and the Astigo River. They were one of three such scouting bands circling the besieged city in order to discover any approaching relief forces. Lord Narhaz, the ‘great-thane’ commanding the army of Karak Borgo, had every reason to expect the enemy to attempt a relief, for not only was the tyrant Razger Boulderguts reportedly returning to the city having completed his grand (and very profitable) chevauchee, but there were also reports of an ogre garrison at Ravola to the north and smaller forces scattered throughout Campogrotta’s compass. The ogres’ iron grip on the entire realm had relied on gangs of club-wielding brutes to ensure the native citizens’ continually cowed obedience, and any or all of these ogres could be on the move.

Evrart, the longest serving Brabanzon mercenary amongst the riders, his toothless mouth and sunken cheeks belying his sturdy toughness and considerable strength, rode at the head of the little band, regaling his friend Bossu with his latest theory.

“Ask anyone,” he suggested, “even the locals. No-one has ever seen him.”

“Well, wizards like to keep to themselves,” said Bossu.

“Not always. That dwarf Glammerscale’s been riding with Jacquot’s lads, if you can call it riding. He’s full of friendly conversation.”

“Dwarfs aren’t proper wizards, so that don’t prove anything.”

Evrart pondered this a moment. “Alright,” he admitted, “I’ll grant you that. But what about Perette? She doesn’t exactly hide herself away; quite the opposite. Not that I’m complaining.”

“She’s not what you’d call ‘proper’ either,” said Bossu with a grin.

“Well, no. But they’re both just petty wizards. I’m talking about the great ones like Niccolo. They get noticed.”

“Not so,” said Bossu. “Most wizards shut themselves up in a tower or some such place and go about whatever strange wickedness they’ve set their minds to.”

“Perette doesn’t need any tower to be wicked,” joked Evrart, now grinning himself.

Their conversation stopped a moment as they heard a horn from up ahead.

“That’s the others,” said Evrart. He tugged the reigns a little to send his horse, his companions following, in the direction of the sound. Bossu kept by his side and returned to the topic in hand.

“I’m talking about the mighty wizards too. They say Niccolo’s lived more’n twice as long as anyone should hope for or expect, harbouring his grudge until he returned to retake the city with the ogres. No-one had heard of him for decades – everyone thought he was dead. That’s a lot of practice at hiding away. Now he’s returned, maybe he’s trying to finish off whatever it was he was doing before the Campogrottans threw him out?”

“I don’t buy it,” argued Evrart. “If Lord Niccolo really ruled that city, there’d be at least one report of him. Instead everyone talks about the ogres, about Razger and Wurgrut. How they took the city, then took Ravola, then robbed their way through Tilea. Razger gives the orders, his brutes do the damage. I don’t see how Niccolo fits in at all. You saw yourself, Bossu, it was their banners on the city towers, no one elses.”

“Oh, and you know Lord Niccolo’s coat-of-arms do you?”

“No, but I know it isn’t a line of teeth-mountains or a bull’s skull tied to a pole with catgut. He’s a nobleman of an ancient family. All the rulers are here, even the vampires, just like home. It’ll be some flowery leaf or a golden crown or fancy swirls in bright green or red or …”

“You’ve no idea what it is!”

“Ah, but I don’t need to know to make my point. Those banners were ogre banners. The whole realm is ruled by ogres. It’s Razger who leads the armies - he decides what they’ll do – so it’s no surprise that they spend all their time smashing places up and plundering. If Niccolo was some great and mighty wizard kept o’er long in this world by necromancy, then why didn’t he make an appearance on the walls during the assaults? Why didn’t he fling lightning down, or summon the undead to serve in the defence? Brute ogres, that’s all that was seen; blood-spattered shamans waving bloody innards about. That’s all.”

“From what I’ve heard of the assault, I doubt our lads would have noticed some old man amongst the brutes. What’s a flash of lightning here and there when Razger’s lads are shooting cannons like handguns and the walls are tumbling left and right?”

“Well,” said Evrart, “Let us see what’s what when we take the city. I’ll bet you ten silver ecus that there’s no sign of any wizard, nor even that there ever was one besides them butcher-shamans. Wizard Lord Niccolo’s nothing but a story.”

“I’ll take that bet,” said Bossu. “And you’ll pay me as soon as you get your share. I’m not waiting to hear your drunken excuses after you and your purse disappear into the stews for a week.”

The horn-blowing riders were the other half of their own band – led by a veteran called Raol - who had split off earlier in the day to sweep a little further north and so cover more ground, aiming to rendezvous near the strangely shaped black-rock they had camped at on their last circuit. Upon meeting it was immediately apparent the new arrivals did not intend to stop, so the two groups merged to ride as one.

The riders were mounted on good horses, but not destriers like the nobility of Bretonnia favoured in battle, nor palfreys like the same nobles rode when travelling. These horses were best described as rounceys, trained for both long journeys and battle, but not able to support the weight of a plated knight and barding. Each soldier wore a light armour of chainmail and carried long spears, so they could deliver a charge if the opportunity arose, and sported parti-coloured yellow and green shields, being the company’s livery. Every one of them also carried bows and quivers, allowing them to loose volleys at a distance to harry the foe. As they rode now, some clutched their spears, their bows wrapped in waxed linen and slung across either their own back or their mounts; while others held their bows, their spears slotted into long pouches behind their saddles and their shields slung on harness hooks. One or two, Evrart and Raol included, found it more convenient to have both weapons wrapped and bagged while they concentrated on riding and keeping an eye out. They had experience enough to know that should trouble arise, they would have time to prepare whichever weapon they needed, and if they hadn’t time, then they could draw their swords in a moment.

“News, then?” shouted Evrart to Raol, as they both rode at the head of the reconstituted column.

“Aye, and not good. There’s more coming.”

“Razger?”

“Don’t think so,” said Raol. “This lot came from Buldio.”

“Could be some trick of Razger’s, trying to swing around and arrive where he ain’t expected?”

“We thought so too,” said Raol. “So to make sure we got a proper look at them. They’re just a band of bulls, too small in number to be Razger’s army - no warmachines, no baggage, an’ only one banner. I reckon they’ve been off bullying Buldio, but now ordered to return.”

“Could they be meeting with Razger?”

“If that’s their plan, then they’re meeting at Campogrotta. The road they’re taking leads straight there.”

…

(An hour later.)

As they reached the southern stretch of the rocky-ground they spied one of the other two bands of riders heading their way, led by the riders’ commander, Sergeant Huget. The company’s colours were easily made out at the sergeant’s side, long before much else could be seen. Once again the two groups rode towards each other …

… to join each other on the move; and once again Evrart kept his place at the fore, thus joining the sergeant. As they made their way to the path they had found previously, which led through the wide band of rocks bounding the southernmost reach of this stony land, he reported all he had learned to the sergeant. By the time he finished they had entered the gap through the rocks.

“They’re not the only enemy heading this way,” said the sergeant. “We’ve seen more on the Iron Road.”

“Razger?” asked Evrart.

“I don’t think so. They’re much the same as you described, except that there were greenskin runts with this lot too. And they were coming from the east not the west, which is where Razger will come from.”

“They can’t be from the Lugo watchtower, that place was dead. And there’s no way they came down the Iron Road,” said Evrart.

“No, I reckon they came from the villages of Sermide, only they went north to meet the road before they turned west, instead of just going straight to Campogrotta. They might be planning to meet the ones you saw. ‘Twould explain their diversions.”

“They’re bringing everything they can, then?” asked Evrart.

“As to be expected,” said the sergeant.

“So does that mean Razger’s coming too?”

“Who knows? If he is, then the army’s in big trouble because the enemy’s closing from all sides. If he isn’t, then the army still needs to know about this lot because they’re trouble enough.”

Padre

Lord

Game Note: The following game continues almost from the point the previous battle ended, but now the ogres have two 400 pts relief forces, one entering from the north side, the other from the south, as well as a few newly-bought maneaters bribed (using saved ‘Supply Points’ in the city’s coffers) to help on the defence of the city. This scenario came about due to the fact that the first assault was a technical draw (as per the campaign siege-assault rules) even though the attackers very obviously had the upper hand. Also, because the battle took place at the very end of the summer season, thus (again a technicality) the end of season phase kicked in and reinforcements could be created and ordered. What would be a simply some number-crunching in a board-game style campaign thus drove the creation of the above story-piece and the wargame below. Without the relief forces, the battle would have not been worth fighting, being a foregone conclusion. But with the extra forces performing a pincer attack we decided it was game on!

The Second Assault on Campogrotta: The Battle

Part 1: Deployment and Turn One

The army of Karak Borgo waited four days for their master engineer to declare it was safe to recommence firing Granite Breaker. The engineer spent that time scrutinising every square inch of the enormous barrel – no easy thing considering its massive iron weight had to be lifted aloft by a hastily constructed hoist, to a height of just more than the width of a dwarf, allowing him to crawl beneath, there to inspect the underside. As was the dwarven way he was not to be rushed, taking his time to do the job thoroughly. Not one dwarf thought to complain, bar Glammerscale the wizard, who ought never be taken as an example of a typical dwarven attitude. The Brabanzon mercenaries, on the other hand, found the delay most frustrating - to them the city seemed ripe for the taking. They had to console themselves with the notion that once the massive gun continued its booming battery, the enemy would be so distracted and distressed that the mercenaries’ casualties during the assault should be much less than otherwise they might.

Meanwhile the bombardment was maintained by the mighty engine’s smaller counterparts: cannons, bolt throwers and the archaically fashioned stone thrower the Brabanzon had brought in pieces through the mountain pass, then pegged and lashed together with practised skill. Their combined efforts paled into insignificance compared to Granite Breaker’s earlier work, but it showed the enemy the besiegers were awake and able to hurl missiles perfectly capable of punching right through ogre flesh and bones, if not very effective against the stone walls.

The besiegers kept a constant, close eye upon the shattered walls and towers, expecting a sally would surely be launched against them, but it seemed the defenders had not the numbers for such. Either that, or they were awaiting some other development. In the meantime, despite the steady barrage of bolt and ball, the surviving ogres patrolled the walls with their own brass and iron pieces, with smouldering slow-match always to hand.

Some brutes, as if careless of whatever could be thrown at them, patrolled the mounds of rubble where the walls had tumbled. Others occasionally wandered outside the walls. Perhaps curiosity had got the better of them? Or they wanted to flaunt their contempt of the dwarves and men dispersed about the city?

Some of these even re-crossed the rubble to return inside, although several never came back, simply adding new, grey heaps to the already large mounds of tumbled stones.

When their hired Brabanzon scouts returned in the afternoon of the fourth day the army of Karak Borgo learned exactly why the ogres were biding their time. The riders reported the approach of two separate relief forces, from both the north and the south-east. An hour later, when the master engineer was finally satisfied (and not a moment sooner), the re-loading of Granite Breaker began and the ‘Great Thane’ of Dravaz, Lord Narhak, ordered the call to arms.

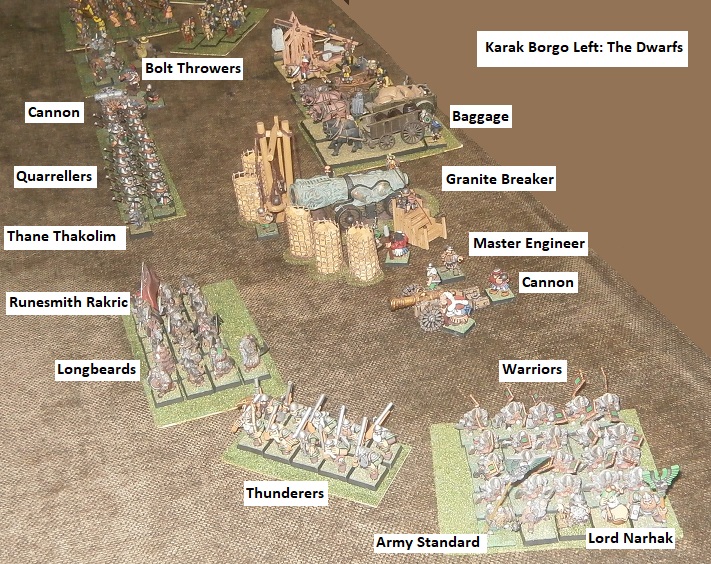

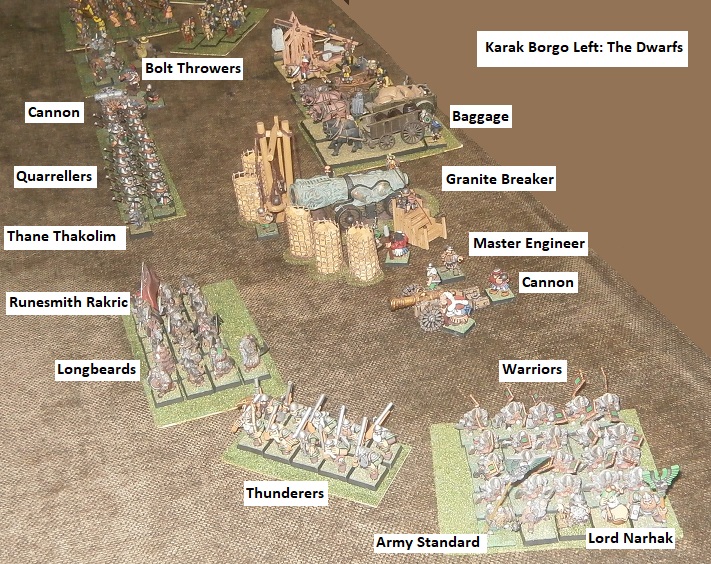

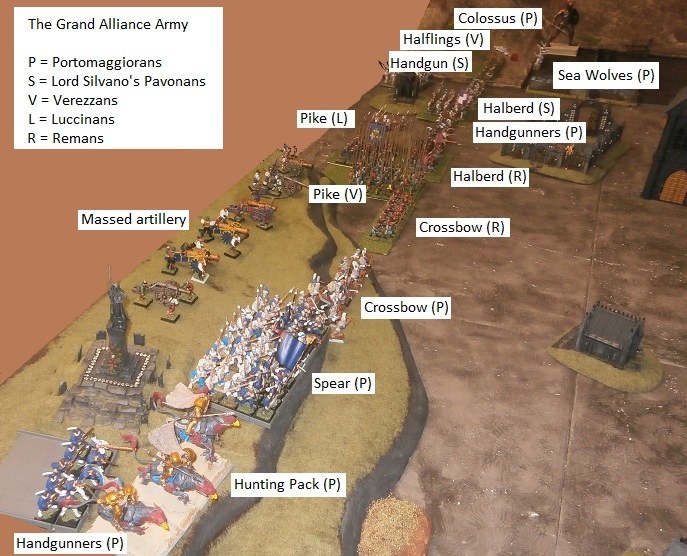

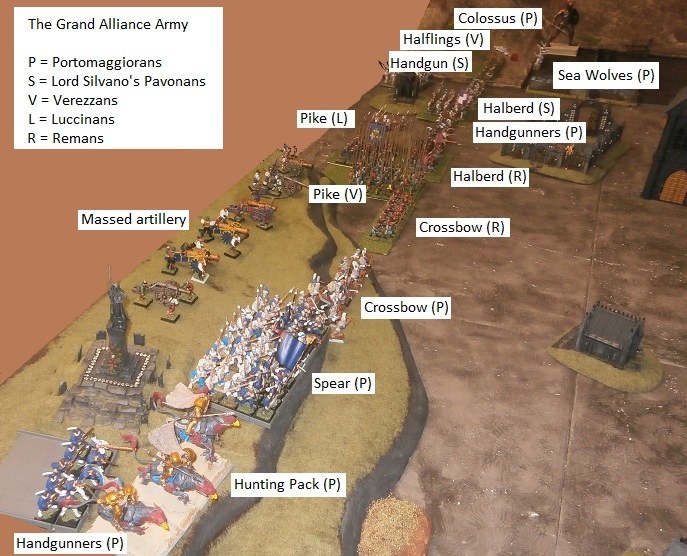

The army drew up in a rather different manner than last assault, for they knew the foe would come from up to three sides. The dwarfs formed a defensive arc afore their artillery pieces. The scouts had reported greater numbers approaching from the south-east, so Lord Narhak joined his warriors to form a barrier to that side, while his thunderers and longbeard veterans stood upon his flank, along the front of the line.

Beyond them, closer to the centre of the line, were the dwarven quarrellers, then the cannon and bolt throwers, with Granite Breaker behind (able to shoot over the rest). Upon the right of the line were the mercenary Bretonnians, the Brabanzon, their main regiment of foot-soldiers providing the more solid defence, while longbowmen and brigand archers formed close by to sting any who approached from that side. The Brabanzon horsemen, now reconstituted into one body, patrolled the front of the line (Game Note: Here having already made their vanguard move.) …

Baron Garoy and his youthful knights rode upon the far-right, hoping to be the first to engage any foe approaching from that flank. They had lost several of their number during the first assault merely attempting to cross the rubble of the breaches and were now hoping to engage the foe on the flat, for that would mean either glory through victory or defeat in combat, and not the ignominy of death due a fall.

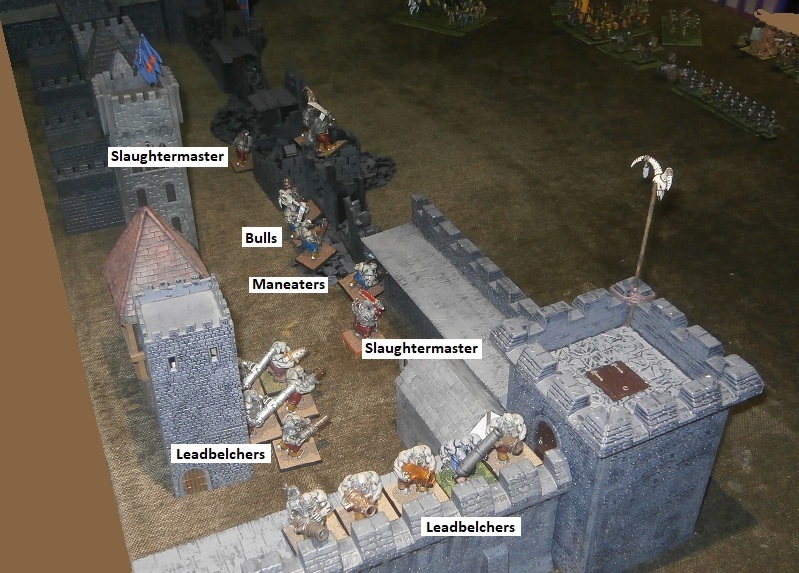

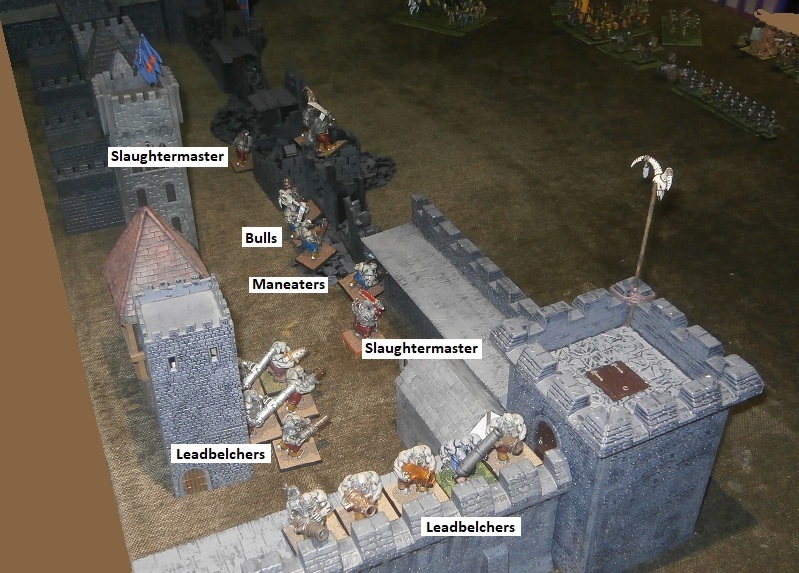

The defenders clustered mainly behind the southern walls, before the dwarven line. The slaughtermaster Wurgrut joined the newly recruited maneaters behind one of the few stretches of wall that had yet to tumble, while one of the two surviving companies of leadbelchers awaited even further within for orders concerning where and when to move up.

The other leadbelchers had mounted the southern wall, where, considering they could not even see the attackers, they too awaited orders. Wurgrut’s second in command skulked with the last of the bulls behind the ruinous gate.

Such were the dispositions as the second assault was to begin.

As Sergeant Huget led his riders towards the wall, to get a closer and therefore better look at what appeared to be a very weakly defended stretch …

… the ogres took the bold manoeuvre as a sign that battle was about to commence. The leadbelchers on the southern wall …

… having ladders ready on the ramparts, descended outside the walls, and crept as best they could, whilst hefting their heavy metal burdens, towards the corner tower.

The remainder of the garrison merely shuffled and stretched to peek out through the ruins here and there. One of the maneaters, his ridiculously oversized head ornament (Game Note: Sorry Jamie, but even you have to admit it is a bizarre headdress/mask combination!) as well as the semi-collapsed ruins obscuring his view, had spotted the horsemen closing on the walls, but then quickly lost sight of them.

He shouted across to second slaughtermaster further along the wall, who responded by conjuring up the spell known as Braingobbler to work a fearful doubt into their minds. Sergeant Huget’s angry shouts, laced as they were with more than a hint of the panic the ogres’ enchantment had sent speckling through him also, failed either to reassure or cow his men, and the riders turned and fled. (Game Note: They failed the dispel roll and their re-rolled panic test – the Brabanzon army standard was within 12”) This initial discouragement, however, had little effect on the rest of the Brabanzon, for most simply assumed the riders had seen whatever they had seen, then chosen to fall back to a safer distance. When the horsemen did indeed rally and reform, this seemed only to confirm the mistaken assumption.

Amongst the riders it was the veteran Evrart who spoke first.

“That was magic, lads. Nasty and peculiar. But none of us is hurt, so let’s put it behind us. If that’s all they have, then it’s a good thing, not bad. Such as that shan’t cut or bruise us, nor break our bones, just give us bad dreams.”

He took a hearty gulp of the dwarven ale in his costrel, as did several others a moment later. Then the sergeant asked, “Ready?” and after a smattering of Ayes, they reformed their body.

The only regiment to move amongst the attackers were the Brabanzon longbowmen, looking to find themselves an opportunity to shoot. The dwarven crossbowmen already had their opportunity …

… and sent a storm of bolts at the Slaughtermaster. These clattered upon the stone all around him, and even struck his body, but some magical ward he possessed thwarted those few that otherwise might have cut into him. He grinned, revealing his maw of splintered teeth and bloody gums, and reached out to pluck a bolt from the mortar it had embedded itself in, thinking it might serve well as a toothpick. But then his eyes widened as he noticed the black shape of a roundshot skipping towards him. If he hadn’t already moved to grab the bolt, the ball would have hit him square on, instead it brushed his arm to leave a large, black bruise. (Game Note: This was technically a direct hit and he failed his ward, but then its D6 wound roll came up 1!)

Below Granite Breaker’s muzzle, one of the matrosses reached aloft to tip the wooden container holding the iron ball, and sent it rolling down to join the two already inside.

The crew did not bother to wad or ram the shots home (to do so would take another half an hour) but instead moved away from the front and cupped their hands over their ears, their thumbs splayed out at the back so as to relieve the pressure that was about to shudder its way through their heads. The chief gunner dipped his extra-long linstock so his mate could blow on the coals, then swung it up and over to lower the glowing end of the match down onto the trail of slightly slower-burning powder he had trailed behind the mound of more excitable powder directly upon the touch hole. This gave him just enough time to turn and all but throw himself down the steps of his platform.

The resultant boom was no more nor less loud than its previous efforts, and yet all those before and within the walls still found themselves shocked. The trio of balls missed the stone defences, travelling through one of breaches Granite Breaker had already made, and ploughed several hundred yards into the city, collapsing several houses and punching through many more walls.

Unfortunately, the great gun’s blast had come at a very inopportune moment for the trebuchet’s Brabanzon crew. Two had been winding tension into the tautly coiled rope, another was nursing the catch to hold the winder in place as the rods were removed and replaced to tighten some more, and a fourth, now that the basket was low enough to do so, had begun adding rocks. Who flinched, or slipped, or let go, no-one knows, but the resultant premature release wrecked the machine, killed two crewmen and wounded a third. (Game Note: You have probably guessed – catastrophic misfire.)

Turn 2 to follow.

The Second Assault on Campogrotta: The Battle

Part 1: Deployment and Turn One

The army of Karak Borgo waited four days for their master engineer to declare it was safe to recommence firing Granite Breaker. The engineer spent that time scrutinising every square inch of the enormous barrel – no easy thing considering its massive iron weight had to be lifted aloft by a hastily constructed hoist, to a height of just more than the width of a dwarf, allowing him to crawl beneath, there to inspect the underside. As was the dwarven way he was not to be rushed, taking his time to do the job thoroughly. Not one dwarf thought to complain, bar Glammerscale the wizard, who ought never be taken as an example of a typical dwarven attitude. The Brabanzon mercenaries, on the other hand, found the delay most frustrating - to them the city seemed ripe for the taking. They had to console themselves with the notion that once the massive gun continued its booming battery, the enemy would be so distracted and distressed that the mercenaries’ casualties during the assault should be much less than otherwise they might.

Meanwhile the bombardment was maintained by the mighty engine’s smaller counterparts: cannons, bolt throwers and the archaically fashioned stone thrower the Brabanzon had brought in pieces through the mountain pass, then pegged and lashed together with practised skill. Their combined efforts paled into insignificance compared to Granite Breaker’s earlier work, but it showed the enemy the besiegers were awake and able to hurl missiles perfectly capable of punching right through ogre flesh and bones, if not very effective against the stone walls.

The besiegers kept a constant, close eye upon the shattered walls and towers, expecting a sally would surely be launched against them, but it seemed the defenders had not the numbers for such. Either that, or they were awaiting some other development. In the meantime, despite the steady barrage of bolt and ball, the surviving ogres patrolled the walls with their own brass and iron pieces, with smouldering slow-match always to hand.

Some brutes, as if careless of whatever could be thrown at them, patrolled the mounds of rubble where the walls had tumbled. Others occasionally wandered outside the walls. Perhaps curiosity had got the better of them? Or they wanted to flaunt their contempt of the dwarves and men dispersed about the city?

Some of these even re-crossed the rubble to return inside, although several never came back, simply adding new, grey heaps to the already large mounds of tumbled stones.

When their hired Brabanzon scouts returned in the afternoon of the fourth day the army of Karak Borgo learned exactly why the ogres were biding their time. The riders reported the approach of two separate relief forces, from both the north and the south-east. An hour later, when the master engineer was finally satisfied (and not a moment sooner), the re-loading of Granite Breaker began and the ‘Great Thane’ of Dravaz, Lord Narhak, ordered the call to arms.

The army drew up in a rather different manner than last assault, for they knew the foe would come from up to three sides. The dwarfs formed a defensive arc afore their artillery pieces. The scouts had reported greater numbers approaching from the south-east, so Lord Narhak joined his warriors to form a barrier to that side, while his thunderers and longbeard veterans stood upon his flank, along the front of the line.

Beyond them, closer to the centre of the line, were the dwarven quarrellers, then the cannon and bolt throwers, with Granite Breaker behind (able to shoot over the rest). Upon the right of the line were the mercenary Bretonnians, the Brabanzon, their main regiment of foot-soldiers providing the more solid defence, while longbowmen and brigand archers formed close by to sting any who approached from that side. The Brabanzon horsemen, now reconstituted into one body, patrolled the front of the line (Game Note: Here having already made their vanguard move.) …

Baron Garoy and his youthful knights rode upon the far-right, hoping to be the first to engage any foe approaching from that flank. They had lost several of their number during the first assault merely attempting to cross the rubble of the breaches and were now hoping to engage the foe on the flat, for that would mean either glory through victory or defeat in combat, and not the ignominy of death due a fall.

The defenders clustered mainly behind the southern walls, before the dwarven line. The slaughtermaster Wurgrut joined the newly recruited maneaters behind one of the few stretches of wall that had yet to tumble, while one of the two surviving companies of leadbelchers awaited even further within for orders concerning where and when to move up.

The other leadbelchers had mounted the southern wall, where, considering they could not even see the attackers, they too awaited orders. Wurgrut’s second in command skulked with the last of the bulls behind the ruinous gate.

Such were the dispositions as the second assault was to begin.

As Sergeant Huget led his riders towards the wall, to get a closer and therefore better look at what appeared to be a very weakly defended stretch …

… the ogres took the bold manoeuvre as a sign that battle was about to commence. The leadbelchers on the southern wall …

… having ladders ready on the ramparts, descended outside the walls, and crept as best they could, whilst hefting their heavy metal burdens, towards the corner tower.

The remainder of the garrison merely shuffled and stretched to peek out through the ruins here and there. One of the maneaters, his ridiculously oversized head ornament (Game Note: Sorry Jamie, but even you have to admit it is a bizarre headdress/mask combination!) as well as the semi-collapsed ruins obscuring his view, had spotted the horsemen closing on the walls, but then quickly lost sight of them.

He shouted across to second slaughtermaster further along the wall, who responded by conjuring up the spell known as Braingobbler to work a fearful doubt into their minds. Sergeant Huget’s angry shouts, laced as they were with more than a hint of the panic the ogres’ enchantment had sent speckling through him also, failed either to reassure or cow his men, and the riders turned and fled. (Game Note: They failed the dispel roll and their re-rolled panic test – the Brabanzon army standard was within 12”) This initial discouragement, however, had little effect on the rest of the Brabanzon, for most simply assumed the riders had seen whatever they had seen, then chosen to fall back to a safer distance. When the horsemen did indeed rally and reform, this seemed only to confirm the mistaken assumption.

Amongst the riders it was the veteran Evrart who spoke first.

“That was magic, lads. Nasty and peculiar. But none of us is hurt, so let’s put it behind us. If that’s all they have, then it’s a good thing, not bad. Such as that shan’t cut or bruise us, nor break our bones, just give us bad dreams.”

He took a hearty gulp of the dwarven ale in his costrel, as did several others a moment later. Then the sergeant asked, “Ready?” and after a smattering of Ayes, they reformed their body.

The only regiment to move amongst the attackers were the Brabanzon longbowmen, looking to find themselves an opportunity to shoot. The dwarven crossbowmen already had their opportunity …

… and sent a storm of bolts at the Slaughtermaster. These clattered upon the stone all around him, and even struck his body, but some magical ward he possessed thwarted those few that otherwise might have cut into him. He grinned, revealing his maw of splintered teeth and bloody gums, and reached out to pluck a bolt from the mortar it had embedded itself in, thinking it might serve well as a toothpick. But then his eyes widened as he noticed the black shape of a roundshot skipping towards him. If he hadn’t already moved to grab the bolt, the ball would have hit him square on, instead it brushed his arm to leave a large, black bruise. (Game Note: This was technically a direct hit and he failed his ward, but then its D6 wound roll came up 1!)

Below Granite Breaker’s muzzle, one of the matrosses reached aloft to tip the wooden container holding the iron ball, and sent it rolling down to join the two already inside.

The crew did not bother to wad or ram the shots home (to do so would take another half an hour) but instead moved away from the front and cupped their hands over their ears, their thumbs splayed out at the back so as to relieve the pressure that was about to shudder its way through their heads. The chief gunner dipped his extra-long linstock so his mate could blow on the coals, then swung it up and over to lower the glowing end of the match down onto the trail of slightly slower-burning powder he had trailed behind the mound of more excitable powder directly upon the touch hole. This gave him just enough time to turn and all but throw himself down the steps of his platform.

The resultant boom was no more nor less loud than its previous efforts, and yet all those before and within the walls still found themselves shocked. The trio of balls missed the stone defences, travelling through one of breaches Granite Breaker had already made, and ploughed several hundred yards into the city, collapsing several houses and punching through many more walls.

Unfortunately, the great gun’s blast had come at a very inopportune moment for the trebuchet’s Brabanzon crew. Two had been winding tension into the tautly coiled rope, another was nursing the catch to hold the winder in place as the rods were removed and replaced to tighten some more, and a fourth, now that the basket was low enough to do so, had begun adding rocks. Who flinched, or slipped, or let go, no-one knows, but the resultant premature release wrecked the machine, killed two crewmen and wounded a third. (Game Note: You have probably guessed – catastrophic misfire.)

Turn 2 to follow.

Padre

Lord

Turns 2 – 3

The dwarven Longbeards, commanded by the Runesmith Rakric Bronzeborn, had already begun to move towards the city wall …

… when the ogre relief force from Sermide arrived upon the field, consisting of a company of bulls and a mob of gnoblars. (Game Note: Both relief forces rolled separately, 5+ to arrive on turn 2, 4+ on turn 3, and if still absent, an automatic arrival on turn 4)

Lord Narhak had expected them, and so he was ready. He, his warriors and his army standard bearer, the long-bearded veteran Thane Bragdebreg, had tarried as the longbeards moved away, and so now stood directly in the ogres’ way.

The leadbelchers inside the city, reassured by the fact that Granite Breaker had failed even to chip the defences (and happy to pretend they had not witnessed what its shot had done to the dwellings inside the walls) now ascended onto the parapet, there to be joined by the Slaughtermaster Wurgrut. To their left the Maneaters edged forwards through the rubble, all the better to snipe at the foe using their handgun-sized pistols, while the leadbelchers who had descended from the southern wall now moved out into the shadow of the corner tower.

Wurgrut, having spotted the arrival of the first relief force, now attempted to crush the bones of the dwarven thunderers close to the newcomers, but although his spell was cast, it did little more than make the enemy’s bones ache, while the energies that spilled from his over-hasty efforts hurt stung him and the leadbelchers at his side, and sloughed away what other energies the winds of magic could have provided for both him and his lieutenant. He cursed, partly at the pain of the injury he had received, partly at the frustration of fumbling his magical efforts, but mainly because cursing was his most common form of utterance.

Only momentarily distracted by their comrade’s wound, the leadbelchers on the wall with Wurgut blasted their barrels at the advancing Longbeards, cutting four down. Their success drew the maneaters’ and other leadbelchers’ interest, so that they too gave fire upon the same enemy regiment, but despite spewing great plumes of smoke, they failed to harm any more of the enemy. Rakric Bronzeborn took a puff upon his pipe, and uttered a single, entirely unnecessary, word: “Steady”.

The ragged mob of gnoblars drew close enough to hurl a varied collection of sharp missiles at the dwarven handgunners, killing one. While they whooped and squealed, the dwarves calmly continued making their pieces ready.

Lord Narhak now ordered his warriors to ‘march on’, towards the ogres. This was no charge, but rather an attempt to ensure that the bulls could not slip past the warriors while the gnoblars caused a distraction.

Slowly but surely, the dwarves moved so that the only way either gnoblars or ogres could get to the artillery pieces in the rear was to go through them. One amongst the warriors a drummer named Ringregur beat the steady call required for this manoeuvre whilst staring wide-eyed at the massive brutes ahead.

He had been recruited fresh for this campaign and had never seen battle before, apart from the occasional drunken brawl in the alehouses and halls he entertained in. He did not know it, but Lord Narhak had noticed his expression, recognising the trepidation it revealed. Even as the brute foe began their charge, Lord Narhak leaned towards the drummer and said, “Tough Audience.” Ringregur might have laughed had he had time to do so.

(Game note: I have to admit that as GM, note-taker and photographer, I thought the dwarfs were in a very bad situation. If the ogres got through they could sweep down the line destroying machine after machine before anyone else could get to grips with them, never mind actually stop them. The dwarven player, however, despite commanding an NPC force not his own, knew the capabilities of a dwarven unit with not one but two lords within it better than I, as well as what spells he planned to assist them, and he was confident. Time would tell.)

Glammerscale the wizard, standing between the quarrellers and the stone-filled gabions shielding Granite Breaker’s crew, could see what was happening on the left flank.

Having his most important books at hand, and tasselled bookmarks handily placed, he opened to a richly adorned page containing the bound spell Harmonic Convergence. With little more than a stroke and a word of command, he released the spell and so blessed the warriors for the fight ahead. Emboldened by this success, he turned to a much trickier page, for the spell there was described but not bound. He had studied this page deep into the night, and now read it aloud hoping to call down a comet from the heavens. For a moment he thought it had worked, but then he sensed the unlacing of the etheric winds by the enemy’s magicians, and the possibility was gone. He closed the book but, in hope, left the bookmark in its place.

While the thunderers arguably wasted good powder killing four gnoblars, one of the bolt-throwers injured a leadbelcher, while shots from the smaller cannons tore a bull in half and felled another leadbelcher. Granite breaker struck the last standing section of wall to visibly shake both it and the ogres upon it, which is why Wurgrut accompanied the leadbelchers off the wall to stand boldly upon the outside.

Now that the relief had begin to arrive, the ‘slaughtermaster-general’ did not intend to sit inside the walls as they were torn apart like the last time. Ahead of him, the other company of leadbelchers had already ventured some distance out …

… while to the other side the maneaters and bulls had also emerged from the ruinous walls.

As all these ogres came on, the relief force had already charged: the bulls smashed hard into the steel-clad dwarf warriors; beside them the gnoblars poured onto the much smaller body of dwarven thunderers, leaving five dead from the dwarves’ countershot.

Neither Slaughtermaster could find it in themselves to summon sufficient magical energies to their bidding, and so it was left to the leadbelchers to fell another pair of longbeards. The combats were considerably messier than the shooting. Two dwarven warriors were fatally crushed by the mere impact of the bulls, then the ogres’ clubs broke the neck of another. Lord Narhak viciously bloodied the crusher in command of the bulls, causing him to reel away in pain, while Thane Bragdebreg and the other warriors also carved deep wounds. The bulls, more confused than fearful, found themselves unexpectedly halted. They would need to do a lot more to break through than they had bargained for.

The gnoblars failed even to scratch their tough-skinned, armoured foe, while the dwarves dispatched four of the greenskins. Perhaps because the bulls were still fighting at their side, and despite their usual cowardice, they too managed to fight on. (Game Note: Both units passed their Break tests.) This they immediately regretted, for the surviving longbeards now charged into their flank.

Knowing that Baron Garoy was watching the army’s flank from a little way behind them …

… the Brabanzon riders now spurred their mounts to carry them within bowshot distance of the bulls, coming very close to the ruinous walls to do so.

Both Slaughtermasters had spotted Perette amongst the Brabanzon foot soldiers …

… and both remembered the fire magic she had employed to during the first assault. Keen to avoid such casualties during this last, desperate sally from the walls, both chose to ignore Glammerscale and concentrate on thwarting whatever magic she intended to summon. Thus it was that dwarf wizard managed once again to settle a harmonic convergence onto the dwarf warriors, magically blessing their blade-work.

(Game Note: I know, I know … ‘dwarf’ & ‘wizard’ are not two words Warhammer players expect to see joined together, but the old model itself proves the concept is not entirely impossible. I had to come up with suitable rules for him. Of course, any dwarf army containing him does not get the ‘Natural Resistance’ dispel roll bonus, but this army would have lost this anyway by having the fallen damsel Perette on their side. He also struggles a little more than other with magic - each spell he attempts is +2 harder to cast than the standard casting value. Dwarfs are not natural wizards, so he has to try harder!)

Perette failed to conjure anything anyway, so the ogres’ caution was wasted. The attackers’ shooting, however, was quite impressive. One bolt killed a bull (Note: The player made his third snake-eyes panic test in a row here!), another tore deep into the chief slaughtermaster Wurgut. One of the cannons took down a maneater, while Granite Breaker felled another, and the dwarven crossbow killed a third! Even the Brabanzon riders stuck a few arrows into the enemy. All this damage left only one maneater, two bulls and the second Slaughtermaster in the centre of the field.

To the disappointment of its crew, the mercenaries’ light gun …

… merely buried its ball in the dirt.

The dwarves now hacked the gnoblars apart, and when the last few greenskins fled in terror, both dwarven regiments followed to finish them off and hit the bulls’ flank.

A bloodbath ensued, as Lord Narhak knocked the crusher’s brains out, Bragdebreg killed a bull by himself, and two more bulls were slain by the rest. Such was their prowess, luck and the skill of their shieldwall, that not one dwarf was harmed. The few surviving bulls knew full well to remain would be suicide, and so attempted to flee. They were pursued from the field by the Longbeards.

The threat from Sermide had been dealt with. The threat from Buldio had yet to arrive.

Turns 4-6 to follow.

The dwarven Longbeards, commanded by the Runesmith Rakric Bronzeborn, had already begun to move towards the city wall …

… when the ogre relief force from Sermide arrived upon the field, consisting of a company of bulls and a mob of gnoblars. (Game Note: Both relief forces rolled separately, 5+ to arrive on turn 2, 4+ on turn 3, and if still absent, an automatic arrival on turn 4)

Lord Narhak had expected them, and so he was ready. He, his warriors and his army standard bearer, the long-bearded veteran Thane Bragdebreg, had tarried as the longbeards moved away, and so now stood directly in the ogres’ way.

The leadbelchers inside the city, reassured by the fact that Granite Breaker had failed even to chip the defences (and happy to pretend they had not witnessed what its shot had done to the dwellings inside the walls) now ascended onto the parapet, there to be joined by the Slaughtermaster Wurgrut. To their left the Maneaters edged forwards through the rubble, all the better to snipe at the foe using their handgun-sized pistols, while the leadbelchers who had descended from the southern wall now moved out into the shadow of the corner tower.

Wurgrut, having spotted the arrival of the first relief force, now attempted to crush the bones of the dwarven thunderers close to the newcomers, but although his spell was cast, it did little more than make the enemy’s bones ache, while the energies that spilled from his over-hasty efforts hurt stung him and the leadbelchers at his side, and sloughed away what other energies the winds of magic could have provided for both him and his lieutenant. He cursed, partly at the pain of the injury he had received, partly at the frustration of fumbling his magical efforts, but mainly because cursing was his most common form of utterance.

Only momentarily distracted by their comrade’s wound, the leadbelchers on the wall with Wurgut blasted their barrels at the advancing Longbeards, cutting four down. Their success drew the maneaters’ and other leadbelchers’ interest, so that they too gave fire upon the same enemy regiment, but despite spewing great plumes of smoke, they failed to harm any more of the enemy. Rakric Bronzeborn took a puff upon his pipe, and uttered a single, entirely unnecessary, word: “Steady”.

The ragged mob of gnoblars drew close enough to hurl a varied collection of sharp missiles at the dwarven handgunners, killing one. While they whooped and squealed, the dwarves calmly continued making their pieces ready.

Lord Narhak now ordered his warriors to ‘march on’, towards the ogres. This was no charge, but rather an attempt to ensure that the bulls could not slip past the warriors while the gnoblars caused a distraction.

Slowly but surely, the dwarves moved so that the only way either gnoblars or ogres could get to the artillery pieces in the rear was to go through them. One amongst the warriors a drummer named Ringregur beat the steady call required for this manoeuvre whilst staring wide-eyed at the massive brutes ahead.

He had been recruited fresh for this campaign and had never seen battle before, apart from the occasional drunken brawl in the alehouses and halls he entertained in. He did not know it, but Lord Narhak had noticed his expression, recognising the trepidation it revealed. Even as the brute foe began their charge, Lord Narhak leaned towards the drummer and said, “Tough Audience.” Ringregur might have laughed had he had time to do so.

(Game note: I have to admit that as GM, note-taker and photographer, I thought the dwarfs were in a very bad situation. If the ogres got through they could sweep down the line destroying machine after machine before anyone else could get to grips with them, never mind actually stop them. The dwarven player, however, despite commanding an NPC force not his own, knew the capabilities of a dwarven unit with not one but two lords within it better than I, as well as what spells he planned to assist them, and he was confident. Time would tell.)

Glammerscale the wizard, standing between the quarrellers and the stone-filled gabions shielding Granite Breaker’s crew, could see what was happening on the left flank.

Having his most important books at hand, and tasselled bookmarks handily placed, he opened to a richly adorned page containing the bound spell Harmonic Convergence. With little more than a stroke and a word of command, he released the spell and so blessed the warriors for the fight ahead. Emboldened by this success, he turned to a much trickier page, for the spell there was described but not bound. He had studied this page deep into the night, and now read it aloud hoping to call down a comet from the heavens. For a moment he thought it had worked, but then he sensed the unlacing of the etheric winds by the enemy’s magicians, and the possibility was gone. He closed the book but, in hope, left the bookmark in its place.

While the thunderers arguably wasted good powder killing four gnoblars, one of the bolt-throwers injured a leadbelcher, while shots from the smaller cannons tore a bull in half and felled another leadbelcher. Granite breaker struck the last standing section of wall to visibly shake both it and the ogres upon it, which is why Wurgrut accompanied the leadbelchers off the wall to stand boldly upon the outside.

Now that the relief had begin to arrive, the ‘slaughtermaster-general’ did not intend to sit inside the walls as they were torn apart like the last time. Ahead of him, the other company of leadbelchers had already ventured some distance out …

… while to the other side the maneaters and bulls had also emerged from the ruinous walls.

As all these ogres came on, the relief force had already charged: the bulls smashed hard into the steel-clad dwarf warriors; beside them the gnoblars poured onto the much smaller body of dwarven thunderers, leaving five dead from the dwarves’ countershot.

Neither Slaughtermaster could find it in themselves to summon sufficient magical energies to their bidding, and so it was left to the leadbelchers to fell another pair of longbeards. The combats were considerably messier than the shooting. Two dwarven warriors were fatally crushed by the mere impact of the bulls, then the ogres’ clubs broke the neck of another. Lord Narhak viciously bloodied the crusher in command of the bulls, causing him to reel away in pain, while Thane Bragdebreg and the other warriors also carved deep wounds. The bulls, more confused than fearful, found themselves unexpectedly halted. They would need to do a lot more to break through than they had bargained for.

The gnoblars failed even to scratch their tough-skinned, armoured foe, while the dwarves dispatched four of the greenskins. Perhaps because the bulls were still fighting at their side, and despite their usual cowardice, they too managed to fight on. (Game Note: Both units passed their Break tests.) This they immediately regretted, for the surviving longbeards now charged into their flank.

Knowing that Baron Garoy was watching the army’s flank from a little way behind them …

… the Brabanzon riders now spurred their mounts to carry them within bowshot distance of the bulls, coming very close to the ruinous walls to do so.

Both Slaughtermasters had spotted Perette amongst the Brabanzon foot soldiers …

… and both remembered the fire magic she had employed to during the first assault. Keen to avoid such casualties during this last, desperate sally from the walls, both chose to ignore Glammerscale and concentrate on thwarting whatever magic she intended to summon. Thus it was that dwarf wizard managed once again to settle a harmonic convergence onto the dwarf warriors, magically blessing their blade-work.

(Game Note: I know, I know … ‘dwarf’ & ‘wizard’ are not two words Warhammer players expect to see joined together, but the old model itself proves the concept is not entirely impossible. I had to come up with suitable rules for him. Of course, any dwarf army containing him does not get the ‘Natural Resistance’ dispel roll bonus, but this army would have lost this anyway by having the fallen damsel Perette on their side. He also struggles a little more than other with magic - each spell he attempts is +2 harder to cast than the standard casting value. Dwarfs are not natural wizards, so he has to try harder!)

Perette failed to conjure anything anyway, so the ogres’ caution was wasted. The attackers’ shooting, however, was quite impressive. One bolt killed a bull (Note: The player made his third snake-eyes panic test in a row here!), another tore deep into the chief slaughtermaster Wurgut. One of the cannons took down a maneater, while Granite Breaker felled another, and the dwarven crossbow killed a third! Even the Brabanzon riders stuck a few arrows into the enemy. All this damage left only one maneater, two bulls and the second Slaughtermaster in the centre of the field.

To the disappointment of its crew, the mercenaries’ light gun …

… merely buried its ball in the dirt.

The dwarves now hacked the gnoblars apart, and when the last few greenskins fled in terror, both dwarven regiments followed to finish them off and hit the bulls’ flank.

A bloodbath ensued, as Lord Narhak knocked the crusher’s brains out, Bragdebreg killed a bull by himself, and two more bulls were slain by the rest. Such was their prowess, luck and the skill of their shieldwall, that not one dwarf was harmed. The few surviving bulls knew full well to remain would be suicide, and so attempted to flee. They were pursued from the field by the Longbeards.

The threat from Sermide had been dealt with. The threat from Buldio had yet to arrive.

Turns 4-6 to follow.

Lands Annex

Vassal

Another great passage to wake up to, still enjoying this enormously. Have a happy new year!

Padre

Lord

Thanks for the vote of confidence, Lands Annex. I am really excited for the campaign in 2019, so much planned - modelling & painting; characters & stories; & some big games hopefully. Real big.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Turns 4-6

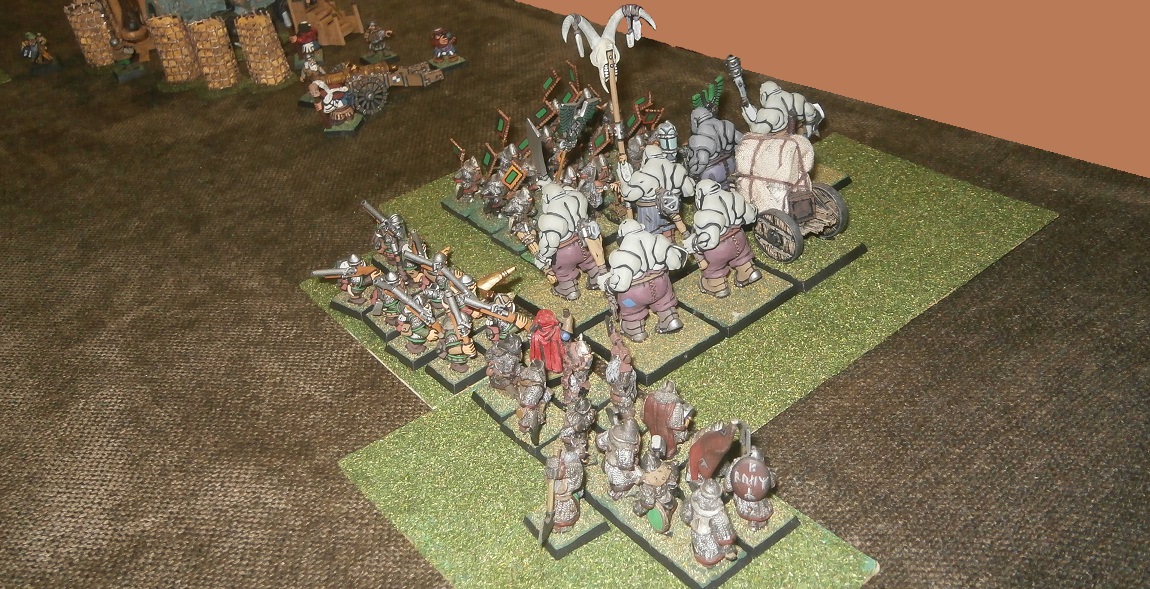

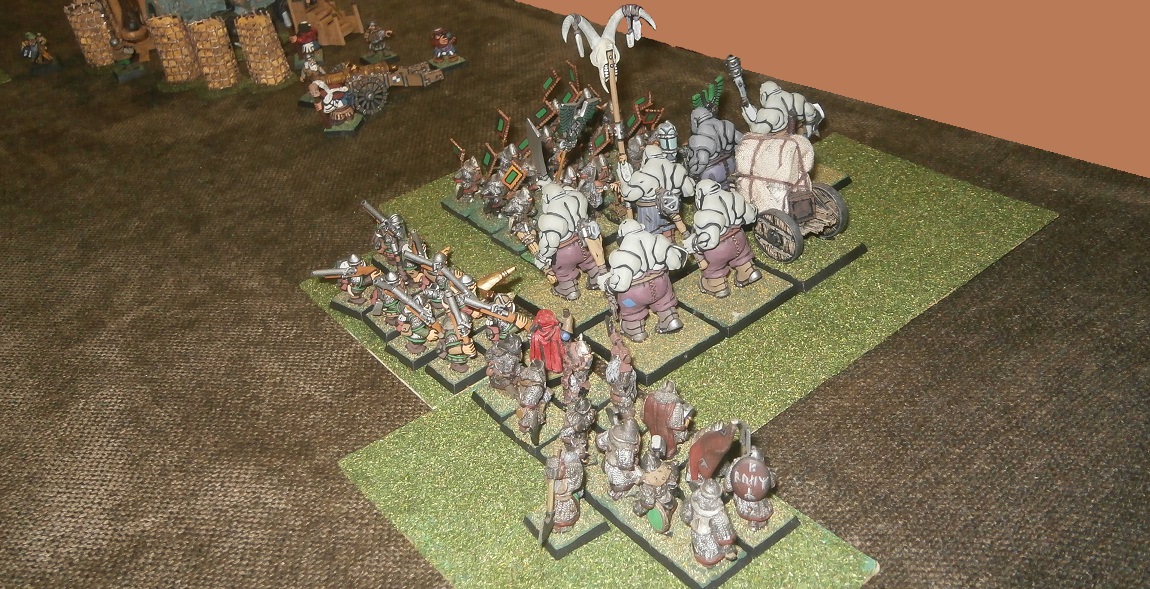

The Buldian relief force arrived just as the last Sermiden was chased away. This new force had no gnoblars accompanying them, consisting only of brute bull warriors with a bruiser in command. Like many ogre regiments of Border Princes’ origins, they wore spiked helmets and gut-plates, carrying huge swords in one hand while their other hands were enclosed in bladed gauntlets of steel.

The bruiser had horns sprouting from both his gut plate and helmet, and he bore two weapons – an ugly, hooked blade and a very hefty iron club adorned with seven conical barbs. He led his company boldly onto the field, as if there were nothing at all to fear. The ogres’ arrival was so sudden, and they moved so quickly, that the young Baron Garoy and his knights, despite waiting with intent for just this occurrence, were taken by surprise, and found themselves unable to deliver their anticipated charge. It did not go unnoticed amongst several knights that the baron had hesitated, if only for the merest moment, and so failed to deliver a prompt enough command. The knights were now forced to turn about if they were to get to grips with the foe.

(Game Note: It was a charge arc issue. I suppose Damo had assumed the ogres would come on closer to the knights, rather than into what had appeared at the start of the game to be a killing ground before several missile units and engines – at that time an insane place to enter.)

One brute upon the Buldians’ right flank was shouting something that none among the Brabanzon could understand. When he was answered in the same alien tongue by a shout from the second slaughtermaster with the last surviving garrison bulls, the soldiers knew exactly what was intended - both ogre companies would coordinate their charges to hit the Branbanzon’s spear-armed foot-soldiers from two sides at the same time. The soldiers were only real fighting body on that flank, apart from the momentarily disoriented knights, for all else were archers and the like.

Upon the far right of the ogres’ line the leadbelchers who had first emerged from the defences, despite having noticed the sparsity of surviving ogres elsewhere before the walls, and as yet unaware that the Buldian relief force had arrived, finally decided to risk a charge at the reformed dwarven handgunners. Their effort, however, was somewhat half-hearted, as if they merely wanted to appear willing before they looked instead to their own survival, and as soon as one of them fell to the dwarves’ perfectly executed volley, they turned and fled from the field and the city.

Their initial, apparently aggressive movement was noticed, however, and spurred the lone surviving maneater and the slaughtermaster with the bulls to have a go too. Neither managed to reach the enemy, instead slowing to a halt as they saw the unexpected flight of the leadbelchers to their right. Wurgrut was sufficiently flustered by what was unfolding before him that he fumbled his attempts at summoning a magical maw, losing control of his creation to harm only himself and his own ogres.

Too distracted by the newcomers, the Brabanzon failed to notice the garrison ogres’ discomfort. Baron Garoy finally brought his knights about so that they might deliver a charge, while the Brabanzon spearmen manoeuvred similarly so that they might receive one!

Perette had no intention of being caught in the imminent deadly mayhem, so she glanced around looking for somewhere safer to be. Spotting the brigand archers in the rear …

… she ran towards them - they were the sort of troops who could move quickly, avoiding trouble, which was exactly what she intended herself. She came to a halt between them and a basket carrying mule …

… and immediately set about attempting magic, but her desperate dash had left her distracted too, and her spells failed to manifest materially.

Bolt, bullet and arrow, both large and small, now came bursting from almost every part of the army of Karak Borgo. Granite Breaker’s mighty shot caused the last maneater to vanish in a red haze, and another leadbelcher fell dead, but much of the shooting was panicked and o’er hasty, especially from the Brabanzon, so that only two of the Buldian brutes fell.

The Brabanzon horsemen’s volley also had little noticeable effect, and they now became onlookers from their somewhat removed position before the ragged walls …

… watching as the Buldian brutes smashed into the front of the Brabanzon spearmen while the second slaughtermaster with the last bull hit them in the flank.

The Brabanzon footsoldiers were of good reputation, at least when it came to battle, if not for restraint when it came to plunder and pillage. Every man was a veteran of at least one war, and they were led by no less than their company’s commander, Captain Lodar ‘the Wolf’, with Jean de Salle, the company ensign, by his side. Yet despite all this, despite bracing themselves and presenting a neatly serried array of spear tips, they were not to prevail. Five died from the mere shock of the brutes’ impact, before even one blade had struck a blow. Captain Lodar was hewn in two, from left shoulder to right waist, and six more soldiers were similarly butchered. So smashed and shattered were the remainder, that they broke immediately. When the brutes came on they cut down and crushed umpteen more, so that the fighting heart of the Brabanzon, as well as their leaders, were gone. The Buldian bulls’ pace had hardly been slowed by this butchery, and they crashed into the dwarven crew of one of the bolt throwers.

At last, Baron Garoy and his companions got to deliver the charge they had been yearning for, into the rear of the ogres.

Baron Garoy himself took on the Bruiser, glad of his armour when the ogre’s giant club thudded into his shield and arm, bending the first and numbing the other. It was all he could do to stay mounted. One knight’s lance struck home, and took down a bull, but the ogres had quickly slaughtered the dwarven crewmen and all now turned to face the Baron Garoy’s company. The knights’ charge was over, their impetus spent, and more than one now wondered whether their one real chance had already passed.

Moment’s before, Perette had seen an opportunity – the second slaughtermaster and the last garrison bull were before her, visible through a momentary gap appearing between the Brabanzon and dwarves.

Having caught her breath and regained her composure she could put all her mind to the task. The fireball she conjured singed her comrades on its flight, and upon striking killed the slaughtermaster and send the last Campogrottan garrison bull stumbling, smoking, choking forwards, only to be riddled with bolts from the quarrellers. Some of the bolts’ fletchings caught fire as he fell dead.

More of the of leadbelchers with Wurgrut fell, while he himself watched in addled fascination as one of Granite Breaker’s massive roundshots skipped off the ground before him to fly only an inch above his head. (Game note: Failed ‘Look Out Sir, but Ward save passed) He cursed, then cursed again for good measure, and although he could see there was still some sort of fighting going on to the enemy’s right, he knew to remain would be madness. He had no intention of dying today. He turned, pushing a leadbelcher to the ground to clear the way, and scrabbled over the tumbled masonry into the city.

The Buldian bruiser was grinning as he struck Baron Garoy again, almost exactly as before. This time the baron’s arm broke and the snapped bone inside dislodged from his shoulder. The force of the blow was too much for any human frame. Dropping his sword, his sight lost to him, he began to tumble from his saddle but was caught by the man beside him. Crying, “The Baron is wounded,” another grabbed his lord’s reins to lead him away. “Away” came another shout, which is exactly what the knights did, with the Buldian brutes pursuing.

(Game Note: Apart from the Baron’s ‘death’ – he was not overkilled – not one other wound was unsaved in the combat. The knights lost their break test, but the ogres could not catch them. I know the baron was actually still alive, however, as I rolled on one of the campaign character injury tables, and death was not the result. Only overkilled characters don’t get the option of rolling on the chart.)

This left the Buldian bulls somewhat exposed. None of the garrison were to be seen, and the knights were too fast for them to reach. Longbowmen, brigands, horse archers, cannons and a bolt thrower surrounded them.

Perette’s next attempt at a fireball was of little effect – merely warming the brutes’ backsides as they slowed. She now watched …

… as a storm of missiles lashed against the ogres. Two more of the brutes fell, leaving only three with the bruiser.

The bulls had no real chance of getting to grips with the foe, and they knew it. Any one of the enemy bodies surrounding them could easily move away, meanwhile the rest would whittle them down to nought if given the chance.

Game Note: Game over, end of turn 6.)

The bruiser growled, hurled his giant club towards the Brabanzon’s little gun, then ordered his men to follow him from the field.

Campogrotta had fallen. This was surely the beginning of the end of the ogres’ tyrannical rule of this northern Tilean realm. Razger had not returned home in time. Should he do so now he would find the dwarves and their mercenaries ready and waiting. Admittedly, the Brabanzon had suffered heavily, so that only their lightest troops remained intact, and had no commander at present to lead them, but the Compagnia del Sole was on its way, reputedly with a force greater than the dwarves’ current army. Considering the ogre forces remaining in the realm of Campogrotta were petty in size and scattered, Razger’s battered army could not hope to prevail.

Perette found herself in the unusual position of being asked by the brigand archers at her side what they should do now. They had personally witnessed her killing of the ogre shaman, and consequently their opinions concerning her had been transformed. As she pondered, Glammerscale joined her and told them the city had fallen, their work was nearly done.

“Just a matter,” he said, “of collecting your portion of the prize.”

He didn’t need to say anything more. The archers ran off, towards the city, along with every other Brabanzon still standing on the field, and as they clambered over the rubble, their shouts and whoops began to reverberate through the streets.

Game Notes:

Thanks Damo for commanding the attackers, as you have done for so many NPC armies. You have a detailed tactical understanding that has always eluded me. I am glad you too wanted to keep Perette and Glammerscale alive. And I agree, for some reason I too am more fond of the Brabanzon than the dwarves. What will become of them now that they have become merely a brigade of light missile troops? What will become of the fallen damsel Perette?

And thank you Jamie for allowing us to play a game which might have seemed a foregone conclusion but which in truth, had your relief forces both arrived on turn 2, or even together on turn 3, and had magic gone more your way, and if a few more of the enemy’s machines had misbehaved, this might have been a very destructive battle indeed for the attackers. It is only right, I suppose, that we played the game in which your own realm’s capital city was under attack. I bet everyone is now wondering where Razger is, and what the mysterious wizard lord Niccolo is up to. For now, only you and I know!

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Turns 4-6

The Buldian relief force arrived just as the last Sermiden was chased away. This new force had no gnoblars accompanying them, consisting only of brute bull warriors with a bruiser in command. Like many ogre regiments of Border Princes’ origins, they wore spiked helmets and gut-plates, carrying huge swords in one hand while their other hands were enclosed in bladed gauntlets of steel.

The bruiser had horns sprouting from both his gut plate and helmet, and he bore two weapons – an ugly, hooked blade and a very hefty iron club adorned with seven conical barbs. He led his company boldly onto the field, as if there were nothing at all to fear. The ogres’ arrival was so sudden, and they moved so quickly, that the young Baron Garoy and his knights, despite waiting with intent for just this occurrence, were taken by surprise, and found themselves unable to deliver their anticipated charge. It did not go unnoticed amongst several knights that the baron had hesitated, if only for the merest moment, and so failed to deliver a prompt enough command. The knights were now forced to turn about if they were to get to grips with the foe.

(Game Note: It was a charge arc issue. I suppose Damo had assumed the ogres would come on closer to the knights, rather than into what had appeared at the start of the game to be a killing ground before several missile units and engines – at that time an insane place to enter.)

One brute upon the Buldians’ right flank was shouting something that none among the Brabanzon could understand. When he was answered in the same alien tongue by a shout from the second slaughtermaster with the last surviving garrison bulls, the soldiers knew exactly what was intended - both ogre companies would coordinate their charges to hit the Branbanzon’s spear-armed foot-soldiers from two sides at the same time. The soldiers were only real fighting body on that flank, apart from the momentarily disoriented knights, for all else were archers and the like.

Upon the far right of the ogres’ line the leadbelchers who had first emerged from the defences, despite having noticed the sparsity of surviving ogres elsewhere before the walls, and as yet unaware that the Buldian relief force had arrived, finally decided to risk a charge at the reformed dwarven handgunners. Their effort, however, was somewhat half-hearted, as if they merely wanted to appear willing before they looked instead to their own survival, and as soon as one of them fell to the dwarves’ perfectly executed volley, they turned and fled from the field and the city.

Their initial, apparently aggressive movement was noticed, however, and spurred the lone surviving maneater and the slaughtermaster with the bulls to have a go too. Neither managed to reach the enemy, instead slowing to a halt as they saw the unexpected flight of the leadbelchers to their right. Wurgrut was sufficiently flustered by what was unfolding before him that he fumbled his attempts at summoning a magical maw, losing control of his creation to harm only himself and his own ogres.

Too distracted by the newcomers, the Brabanzon failed to notice the garrison ogres’ discomfort. Baron Garoy finally brought his knights about so that they might deliver a charge, while the Brabanzon spearmen manoeuvred similarly so that they might receive one!

Perette had no intention of being caught in the imminent deadly mayhem, so she glanced around looking for somewhere safer to be. Spotting the brigand archers in the rear …

… she ran towards them - they were the sort of troops who could move quickly, avoiding trouble, which was exactly what she intended herself. She came to a halt between them and a basket carrying mule …

… and immediately set about attempting magic, but her desperate dash had left her distracted too, and her spells failed to manifest materially.

Bolt, bullet and arrow, both large and small, now came bursting from almost every part of the army of Karak Borgo. Granite Breaker’s mighty shot caused the last maneater to vanish in a red haze, and another leadbelcher fell dead, but much of the shooting was panicked and o’er hasty, especially from the Brabanzon, so that only two of the Buldian brutes fell.

The Brabanzon horsemen’s volley also had little noticeable effect, and they now became onlookers from their somewhat removed position before the ragged walls …

… watching as the Buldian brutes smashed into the front of the Brabanzon spearmen while the second slaughtermaster with the last bull hit them in the flank.

The Brabanzon footsoldiers were of good reputation, at least when it came to battle, if not for restraint when it came to plunder and pillage. Every man was a veteran of at least one war, and they were led by no less than their company’s commander, Captain Lodar ‘the Wolf’, with Jean de Salle, the company ensign, by his side. Yet despite all this, despite bracing themselves and presenting a neatly serried array of spear tips, they were not to prevail. Five died from the mere shock of the brutes’ impact, before even one blade had struck a blow. Captain Lodar was hewn in two, from left shoulder to right waist, and six more soldiers were similarly butchered. So smashed and shattered were the remainder, that they broke immediately. When the brutes came on they cut down and crushed umpteen more, so that the fighting heart of the Brabanzon, as well as their leaders, were gone. The Buldian bulls’ pace had hardly been slowed by this butchery, and they crashed into the dwarven crew of one of the bolt throwers.

At last, Baron Garoy and his companions got to deliver the charge they had been yearning for, into the rear of the ogres.

Baron Garoy himself took on the Bruiser, glad of his armour when the ogre’s giant club thudded into his shield and arm, bending the first and numbing the other. It was all he could do to stay mounted. One knight’s lance struck home, and took down a bull, but the ogres had quickly slaughtered the dwarven crewmen and all now turned to face the Baron Garoy’s company. The knights’ charge was over, their impetus spent, and more than one now wondered whether their one real chance had already passed.

Moment’s before, Perette had seen an opportunity – the second slaughtermaster and the last garrison bull were before her, visible through a momentary gap appearing between the Brabanzon and dwarves.

Having caught her breath and regained her composure she could put all her mind to the task. The fireball she conjured singed her comrades on its flight, and upon striking killed the slaughtermaster and send the last Campogrottan garrison bull stumbling, smoking, choking forwards, only to be riddled with bolts from the quarrellers. Some of the bolts’ fletchings caught fire as he fell dead.